After winning a close mayoral election, Wilson’s challenges are just beginning, with Harrell leaving behind a budget mess.

Mayor Bruce Harrell’s 2026 City budget proposal involved several new revenue sources but has failed to address Seattle’s long-term structural deficit. The City projects the 2027 deficit will exceed $127 million, and economic turmoil and increasing chaos and hostility from the federal government further undermine the future financial stability of the city.

As the Seattle City Council nears the finishing line for the city’s 2026 budget, some councilmembers seem determined to limit Mayor-elect Katie Wilson’s options once she takes office in January.

Harrell’s budget proposal used two direct new revenue sources: a 0.1% “public safety” sales tax increase and a business & occupation (B&O) tax restructure, dubbed the Seattle Shield Initiative and just greenlit by voters. Additionally, the new Families, Education, Preschool, and Promise (FEPP) Levy, recently approved by voters, more than doubles the amount of money the City will be collecting compared to the levy’s previous iteration.

Some of this new funding has been allocated in such a way as to free up General Fund, JumpStart payroll tax, and sweetened beverage tax dollars for other purposes. According to a Central Staff memo, these sources created an additional $148 million of new resources for the General Fund, some of which was used to backfill a Jumpstart tax shortfall and some of which was used for new spending priorities, including more money for the Seattle Police Department (SPD), the Community Assisted Response & Engagement (CARE) department, and the Downtown Activation Plan (including another boost to the City’s graffiti abatement program).

Wilson will have to grapple with a future budget deficit that grew in spite of the amount of new resources identified this year.

Budget Chair Dan Strauss’s balancing package, introduced earlier in November, included an additional $45 million in new spending, divided between each councilmember’s priorities. For his part, Mayor Harrell proposed $53 million in new spending, layering on top of about $100 million in new spending approved in his previous budget.

The balanced 2026 budget relies on a one-time $141 million fund balance left over from 2025, as well as a permanent assumed $10 million annual underspend. Many of the items funded in 2026 utilize one-time funding only, including some of the Seattle Shield funding going to backfill federal cuts. If Wilson wants to continue any of these one-time investments in 2027, the deficit will increase.

Central Staff called this approach “inherently unsustainable” since one-time funds create fiscal cliffs for ongoing programs: “While the use of these new resources is a well-intended effort to support priorities that enhance the community, it must be made clear that few clear options, other than potentially drastic and immediate cuts, remain to respond to future fiscal challenges.”

Putting it more bluntly, PubliCola’s Erica Barnett described the budget as balanced only by accounting “tricks” and short-term patches, handing his successor a mess to clean up in an economic environment that is likely to be more challenging.

While Seattle’s most recent revenue forecast was more favorable than was expected, it included a high amount of uncertainty about the city’s economic trajectory. In October, Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi said that states representing one third of the nationwide GDP are either in a recession or at high risk of one, including Washington state.

The risk of the artificial intelligence (AI) technology bubble bursting is another concern. The seven largest tech giants, accounting for 37% of the S&P 500’s total value, are all heavily invested in AI technologies. Their spending spree has temporarily propped up the economy, but fears are growing about the possibility of the AI bubble bursting, causing painful economic fallout.

In Seattle, such an occurrence would particularly impact the JumpStart payroll tax, since tech giants are the biggest payers of the tax. When passed, JumpStart was mainly intended to fund affordable housing, but Harrell has taken to using it to backfill the General Fund.

Federal overreach darkens outlook

Earlier this month, in the shadow of the continuing federal government shutdown, both community members and local governments were working to try to mitigate the potential suspension of the SNAP food aid program, which would have led to many in the region going hungry. States are bracing for the SNAP and Medicaid (Apple Health) eligibility changes rolling out over the next year and struggling to keep up with policy changes that impact funding to a variety of different programs.

A recent federal policy change that is likely to lead to deep cuts in King County’s housing and shelter programs–especially permanent supportive housing – illustrates both the caprice and the cruelty behind the federal government’s approach.

Late last Thursday night, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released its latest Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for its Continuum of Care (CoC) contracts. Seattle and King County receive $65 million in these contracts every year, of which about $60 million is used for permanent housing, per Jennifer LaBrecque from Seattle’s Office of Housing, who spoke to the budget committee last week.

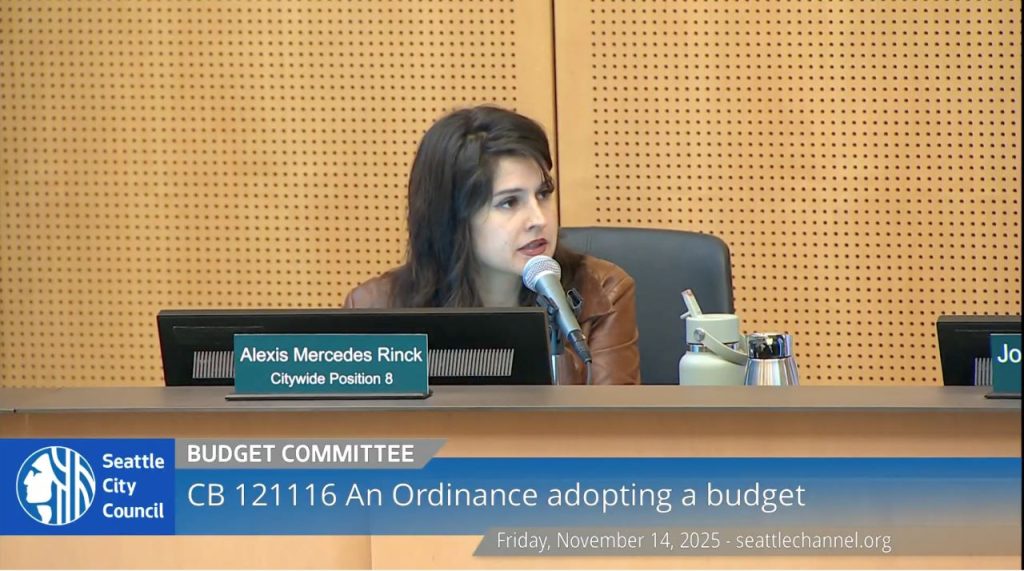

Rinck underscored the devastation these cuts would cause to social programs already spread thin, and pointed out that the idea came out of Project 2025, the 920-page ultra-conservative policy manifesto hatched by the billionaire-backed Heritage Foundation and embraced by the Trump administration.

“After months of delay, the NOFO has finally been released late last night, after hours, and under the sweeping changes, it is estimated that 170,000 people across the United States could fall into or in many cases, back into, homelessness,” Rinck said. “To be clear, this is directly out of the Project 2025 playbook. The federal CoC program plays a major role in housing people who may not otherwise be able to house themselves, including families, veterans, people with disabilities, youth and older adults.”

About $42 million of the CoC funding goes to permanent supportive housing throughout the region, which houses people with serious behavioral health issues that need extra assistance to remain housed. LaBrecque said 17 permanent supportive housing projects in Seattle currently receive $17 million of these dollars every year.

The new NOFO only allows 30% of federal funding to pay for any kind of permanent housing, including permanent supportive housing. This new rule creates a gap of $23 million in the region’s spending on permanent supportive housing.

In addition, the NOFO has been released late, meaning current funding will lapse before new grants are awarded, causing a funding gap that will also jeopardize people’s housing. Less of the funding will now be available year-over-year as a stable basis of funding for programs and projects, instead being put through a competitive process every year.

The new rules also state that permanent supportive housing should only be provided for those who have physical disabilities and/or are elderly, even though this model of housing is specifically designed for people experiencing serious, and often permanent, behavioral health conditions.

The New York Times reported that the new rules allow HUD to reject applicants that used criteria and policies to explicitly help transgender and specific racial groups, “previously or currently.”

It is possible the new CoC rules might be delayed until later next year, and regardless, local officials will shift their applications for CoC grants to try to be competitive within the new rules. But uncertainty abounds as to how successful such an attempt will be.

In order to meet this new funding threat, as well as others that loom on the horizon, Rinck proposed putting a proviso on $11.8 million in the Human Services Department, currently earmarked for a new short-term shelter program proposed by Harrell. The proviso prevents the money from being spent, creating a potential reserve of funds for addressing the CoC changes. Councilmember Bob Kettle whittled that number down to $11.1 million, but the amendment did pass.

The budget already includes investments to backfill federal investments in shelter, emergency housing, and food. Strauss also added $1.06 million for a Federal Response Reserve last week.

Meanwhile, King County Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda added an amendment to the county budget that requests the Executive create a county contingency fund to address the CoC shortages.

Councilmembers try to exert budgetary control over new mayor

In the latest phase of the Seattle budget process, councilmembers have added many amendments to the proposed budget that seem designed to limit Wilson’s options once she enters office.

Perhaps the most striking attempt is Councilmember Rob Saka’s amendment to proviso $29.9 million in several different departments for Unified Care Team (UCT) activities. The UCT performs the City’s homeless encampment sweeps and cleanups and has been one of Harrell’s signature priorities. The proviso would prevent Wilson from spending these funds for other purposes.

The UCT amendment passed on a 5-1 vote; Saka, along with Councilmembers Debra Juarez, Kettle, Sara Nelson, Maritza Rivera, and Mark Solomon voted yes, while Rinck voted no and Strauss and Joy Hollingsworth abstained.

Strauss said he abstained in order to avoid coloring the waters between himself and the new mayoral administration.

“I look forward to working with the next administration to continue and improve the Unified Care Team and how it operates because there are some process improvements. Like anything we do in life, there’s always opportunity to improve, and there’s some good ways that we can,” Strauss said. “So I’m going to abstain from this because I don’t want to muddy those waters without starting into the conversation with the next administration.”

Outgoing Council President Sara Nelson introduced three successful amendments, seeking to dictate policy direction in her absence next year:

- A proviso of $289,000 in the Seattle City Attorney’s Office to continue outgoing City Attorney Ann Davison’s Drug Prosecution Alternative,

- An amendment that prohibits the CIty from using funds for harm reduction supplies for people suffering from substance use disorder (with the exception of needles), and

- A proviso of $4.1 million in SDOT solely for use for graffiti abatement.

Kettle introduced two noteworthy provisos related to SPD spending that were included in the balancing package. One proviso earmarks $26 million of SPD funds to be spent for new sworn staffing, and the other sets aside $4.9 million in SPD for the “Technology Assisted Crime Prevention Program,” aka SPD’s surveillance program that includes CCTV cameras and the real-time crime center.

While Nelson and Wilson’s terms won’t overlap, Saka and Kettle will be working with Wilson next year. Their amendments suggest possible concern that the new Executive has different policy priorities in mind when it comes to encampment sweeps and surveillance.

While the council holds the power of the purse, in practice, provisos only have so much power. Provisos prevent a mayor from spending certain dollars for other purposes, but the mayor can simply refuse to spend the money, full stop, a strategy that might be particularly appealing to Wilson given the unspent money can then be used to address the 2027 budget deficit. Former Mayor Jenny Durkan deployed this strategy on numerous occasions.

Even with budget guardrails via proviso, the Mayor has the ability to set department priorities, hire key personnel, and develop key policies.

With two new councilmembers taking their seats soon – Dionne Foster replacing Nelson and Eddie Lin replacing Solomon – there is also a chance of 2026 budget provisos being lifted next year.

When Wilson takes the helm next year, she has announced that she intends to address the city’s structural budget deficits through a combination of new progressive revenue and targeted cuts.

“I’m very committed to making sure that we’re using our existing resources as effectively and efficiently as possible,” Wilson said at her victory press event last week. “So we’re going to be reviewing the ways that the city is spending money, and I think we’re going to have to do that given the size of the budget deficit. And I am not averse to ending spending on programs that were maybe well-intentioned when they were first implemented but aren’t fulfilling their goals. So we’re going to be doing our very best to be the best stewards of public resources we can.”

Wilson played an important role in passing the JumpStart payroll tax in 2020 and later served on the Revenue Stabilization Workgroup. On the campaign trail, Wilson was an enthusiastic proponent for more progressive revenue.

“I do think that we will need to pursue new progressive revenue in order to fund our priorities and make sure that we’re delivering services to the people of Seattle,” Wilson said. “And you know, there’s several progressive tax options I proposed as part of my platform, and so we’re going to have city staff looking into developing those into legislation.”

Most progressive revenue proposals would either need some lead time to take effect (such as a city-wide capital gains tax) or need state law to be changed in Olympia. Wilson’s timeline will be important in determining the degree to which future budget woes will be able to be addressed via new revenue as opposed to cuts.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.