The City of Sammamish has paused work on a zoning overhaul in its Town Center neighborhood, in the wake of an election that will put three new councilmembers who are growth skeptics into office in January. The victories for Debbie Treen, Michael Boyer, and Josh Amato this month were widely seen as a referendum on the current city council’s approach to growth planning.

Meanwhile, incumbent Councilmember Amy Lam eked out reelection due only to a write-in campaign that split the opposition.

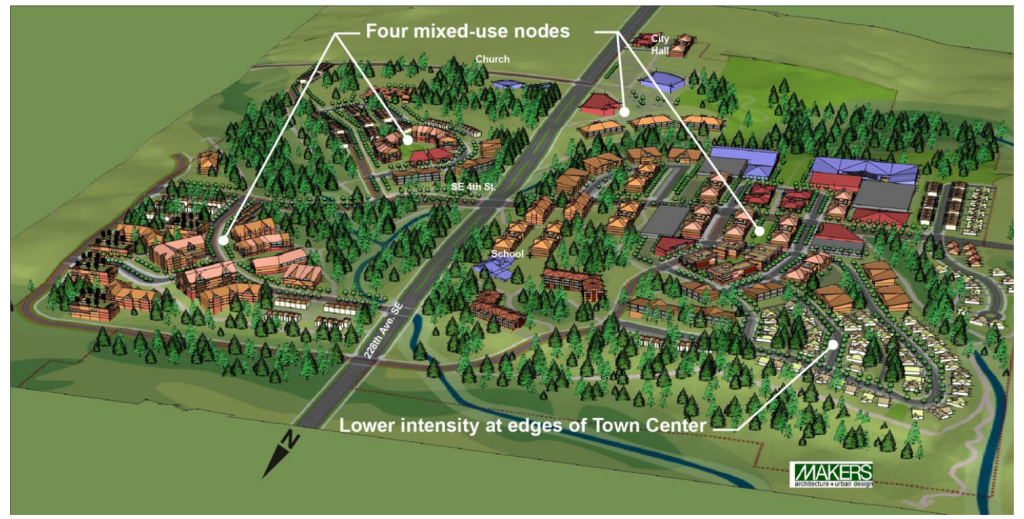

Sammamish has been working on an update to its 2008 Town Center plan since mid-2023. The revision was in response both to newly approved state laws pushing cities to better accommodate future housing needs and to the plan’s meager results over the decade-and-a-half that it has been in place. Most of the development that Sammamish has seen in Town Center, including The Village at Sammamish Town Center — home to Metropolitan Market — has occurred largely in spite of the plan, not because of it.

Earlier this year, the Sammamish Council voted 6-1 to raise the cap on new housing to 4,000 homes as a preferred alternative for an updated Town Center plan’s environmental review, in the face of significant community opposition. In doing so, the majority had sided with Sammamish City staff in their assessment that without increasing Town Center’s overall development capacity, the projects that occur will likely be lower-density townhouses and not mixed-use buildings that bring retail, community spaces, or affordable housing.

The average Sammamish home is valued at $1.6 million, according to Zillow. High home prices and a dearth of new apartments and condominiums severely limits who can afford to live in the city.

Now it will fall to the new city council to decide how dramatically to change course. Reaffirming the higher 4,000-unit ceiling appears unlikely.

“Previously, we had anticipated continuing in our work on this effort. However, with the transition of our city council, we are pausing work on this,” David Pyle, Sammamish’s Community Development Director, told the City’s planning commission last week. “We have directed the consultant team with Framework Consulting to halt their work as of a couple weeks ago, so they are no longer proceeding on any work until we get some redirection from our new city council in the new year.”

One of those newcomers, Debbie Treen, is a former Mayor of Bothell and the wife of Sammamish Councilmember Kent Treen — the only vote against studying the 4,000-home cap. She directly challenged incumbent Mayor Karen Howe over the issue of Town Center. With Boyer and Amato, the two Treens are likely to form a majority bloc on housing issues.

“All across our region, communities are being pushed to accept high density development in the name of affordable housing,” Treen’s campaign website stated. “Sammamish is no exception, but the criteria for such development is not being met. Why? Because the regional policy is for density to be located near mass transit and employment opportunities, two criteria that Sammamish clearly lacks. One size does not fit all!”

Located just east of Redmond and Bellevue, Sammamish’s neighboring cities have embraced urban growth to a much greater degree. Downtown Redmond has added more than 6,000 homes over the last few decades, with more on the way and a similar boom happening at Overlake. Downtown Bellevue has more than 15,000 homes either recently added or in the development pipeline.

Sammamish has been growing at a fairly steady pace in recent years, but with an explosion of single-family homes rather than apartment buildings. Since the adoption of the Town Center plan in 2008, just 326 units were built within the area — and over 3,500 homes went up in the rest of the city, mostly detached units on single lots. Yet what happens at the Town Center has been at the center, so to speak of the city’s discourse around housing since Sammamish was incorporated in 1999.

Outside of this year’s council campaigns, organized opposition to the updated Town Center plan has come most directly from Save Our Sammamish, a group formed earlier this year that can almost certainly claim some credit for election results. Using sensationalized AI-generated images featuring emergency vehicles stuck on gridlocked streets while a wildfire bears down on the city with residents unable to escape in cars, Save our Sammamish painted a vivid picture of the impacts of increased density. The group published one resident’s argument for a full-blown growth moratorium in the city.

“We believe in a Town Center that honors the values of current Sammamish residents—one that prioritizes responsible growth, fiscal sustainability, safeguards our natural environment to include our wildlife, trees, watershed, creeks, and aquifers, and upholds the integrity, infrastructure, and safety of our city,” the SOS website states. “We believe in measured growth, but not without adequate infrastructure. We want the Town Center that was promised to us in 2008, not the housing density boondoggle.”

Completely halting all work on the Town Center isn’t really an option, however.

“Regardless of where we go going forward, there are some fundamental changes that need to be made to the Town Center plan for us to be in compliance with some key state regulations: changes regarding middle housing, regarding parking, regarding accessory dwelling units, there are some things that do need to be changed,” Pyle told the planning commission, alluding to the fact that right now, density limits in Sammamish are higher outside of the Town Center area than inside of it, after changes made to comply with the state’s Middle Housing Law earlier this year.

The bigger question is whether the new council majority retreats to the bare minimum required under state law at the current moment, abandoning changes to Town Center that could be needed to ensure the city meets its requirements longer-term. Under 2021’s House Bill 1220, cities like Sammamish are required to show they have the capacity to accommodate the types of housing that are accessible to households making lower incomes — the majority of the 2,100 new households that the city is required to plan for through 2044 via direction from King County.

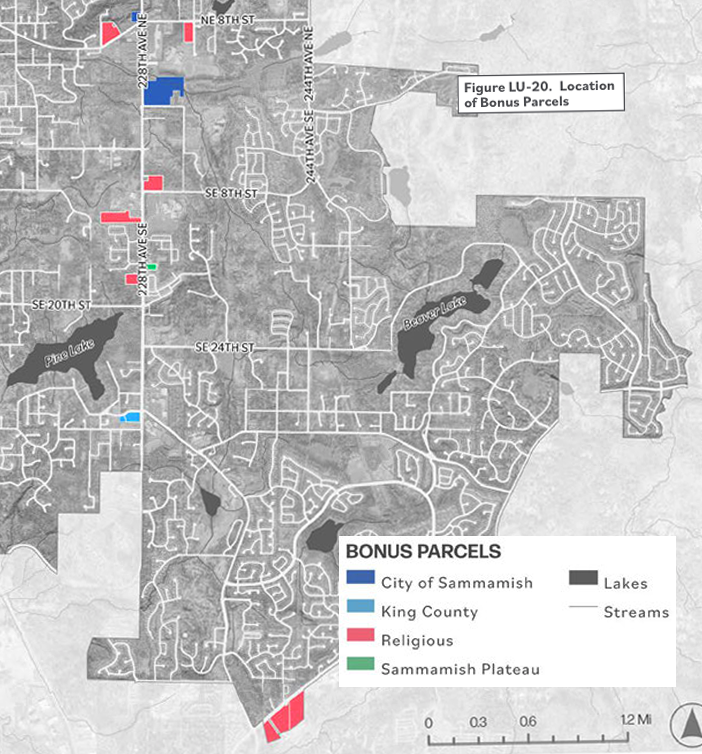

Currently, the city is meeting those requirements through some fuzzy math — assuming that publicly owned properties and parcels owned by religious organizations will be redeveloped in the coming years, development that is required to come with affordable housing under the city’s inclusionary zoning requirements. As long as that development exists on paper, the city argues, it keeps them aligned with state law.

“We are in compliance. However, it takes a lot of work to remain in compliance, and I think the easiest way to understand that is by thinking about it in terms of opportunity cost. So, in order for us to be compliant, we had to show that we had adequate capacity for deeper levels of affordable housing,” Pyle said. “As the Town Center might build out with townhomes, or as other parcels in the city that are our our bonus parcels fill in with other uses and are developed and are not available, we are no longer in compliance because our capacity has been diminished for those areas where we could build mid-rise or low-rise buildings. So, one of the things to keep in mind going forward is that we have to actively maintain compliance, which means that we, every year, have to study if we have enough zoned capacity for low-rise and mid-rise buildings where deeper levels of affordability could be placed.”

The issue of being out of compliance with the state-enforced Growth Management Act (GMA) is not an abstract concept in Sammamish. In 2016, the city was ruled noncompliant when it adopted a citywide Comprehensive Plan update without a plan for Town Center, an issue that was resolved later that year.

In 2020, former Mayor Sammamish Mayor Don Gerend filed another appeal that argued newly adopted requirements around traffic standards were inhibiting development in the Town Center. Rather than fully comply, the city instead enacted a building moratorium while it worked to correct its procedural missteps.

That fight over that Town Center building moratorium, which extended into 2021, saw Karen Howe — not yet elected to the council — call out the move as a “disingenuous means to mask anti-growth attitudes despite the clear and obvious reality of an urbanized region,” the Sammamish Independent reported at the time. Now those anti-growth attitudes have relieved Howe of her council seat and could return the city to the bitter fights that have become a central feature of the city’s short history.

If the new council scales back growth plans, they could put Sammamish on a crash course with an appeal under the GMA yet again. Mercer Island already tested new state laws upping planning requirements and lost, in a case that could set a precedent for other growth-resistant cities across the state.

What happens next remains to be seen. For now, the City will remain in a holding pattern until a planned city council retreat next February.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.