A handful of new affordable housing complexes in Seatte’s South End are providing some welcome relief to apartment-seekers amidst a housing affordability crunch. Permit applications for new apartment buildings in Seattle have plummeted by 39% in the last year, and the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Seattle climbed to $2,200.

Non-profit housing organizations Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) and SouthEast Effective Development (SEED) are working on a slate of projects targeted toward the needs of some of the city’s most racially diverse communities.

Last month, LIHI began leasing units in Nichols Court, a six-story, 148-unit affordable apartment complex at 7544 Martin Luther King Jr. Way S a short walk from the Othello light rail station. Situated on the former site of a tiny home village owned and operated by LIHI for eight years, Nichols Court offers subsidized rentals for those earning up to 50% and 60% of area median income (AMI).

Meanwhile, in Rainier Valley, SEED is hoping to break ground on the Sam Smith Apartments complex next year, the fifth and final building in the Rainier Court complex, which will have transformed a polluted brownfield near Rainier Avenue into housing for 178 individuals and families over the course of 20 years.

Nichols Court

The Nichols Court complex — named for LIHI board president Melinda Nichols, who founded the organization’s tiny home program, and her husband, artist Clifford Nichols – offers a range of units sized from studios to three-bedroom. The two- and three-bedroom units are meant to address the unique needs of ethnically diverse families in the neighborhood, many of whom have multiple generations living under one roof.

“One reason we wanted to serve this community is that it’s the most diverse ZIP code in Seattle,” said LIHI executive director Sharon Lee. Her organization, talking with the community, found that two- and three-bedroom units, which are rare in affordable housing complexes, were in highest demand.

Two-bedroom units at Nichols Court run $1,767 – $2,121 and three-bedroom units cost $2,042 – $2,451, putting them well below the city’s average for a unit of that size.

LIHI has also partnered with Refugee Women’s Alliance (ReWA) to run a day care and preschool on the building’s first floor.

Nichols Court is among a proliferating number of affordable units near the Othello and Rainier Beach light rail stations that have been permitted and built in the past three years.

At an opening event in September, the building’s namesake, Melinda Nichols, a tireless advocate for solutions to the homeless crisis, said, “When Sharon and the board approached me, I said ‘why me? Why not name the building after someone who gives you a lot of money?’ But the board said: ‘Shut up, you worked for 25 years.”

Also at the opening was Seattle Office of Housing director Maiko Winkler-Chin, who highlighted the importance of the new early learning center in her remarks.

“Nichols Court is more than just housing,” Maiko Winkler-Chin said. It’s a place where families can feel supported, connected, and rooted. The ReWA early learning center will be a game-changer for parents and kids alike. We’ll have a safe, affordable, welcoming place to learn, and families will have access to programs and build community and belonging. This really reflects the heart and the spirit of Rainier Valley and how we all take care of each other.”

LIHI’s development cycle — buying a vacant lot, building a tiny home village on it, and then securing funding for and building an affordable apartment building on the property — seems to be a model that’s working well for LIHI.

“It’s a cost-effective strategy to do in some neighborhoods,” Lee said, “especially those experiencing gentrification and displacement — to buy land for future development.”

Other LIHI projects in the works

Friendship Heights, a former LIHI tiny home lot in the North End at 125th and Aurora, will eventually become a building offering 90 units of housing for seniors, Lee says. LIHI is also transforming a surplus Sound Transit property near the Roosevelt light rail station that currently serves as Rosie’s Tiny Home Village into a 12-story affordable housing complex that will be Seattle’s tallest mass timber building when complete. Proponents contend mass timber is both greener and more livable than alternative building materials, such as concrete or steel.

This month, LIHI announced construction on two new tiny home sites: Olympic Hills Village near 133rd Street, and Lake City Way and Church By the Side of the Road Village (CBSR) in Tukwila. Both are slated to be open and running by the end of January. Lee said her organization is also looking at the same strategy somewhere east of Lake Washington.

Overcoming some initial skepticism, Lee said the City of Seattle and the King County Regional Homeless Authority are now firmly behind tiny homes. Seattle, in particular, has set aside funding for three new villages next year and three additional ones in 2027.

Lee says that another tiny home location that LIHI owns, Henderson Village in Rainier Beach, will eventually be developed into a multi-story affordable apartment complex. “That’s a great location. Fabulous. It’s a short walk to Rainier Beach light rail, and a short walk to [Rainier Beach] high school and close to [Be’er Shiva] park and the lake.”

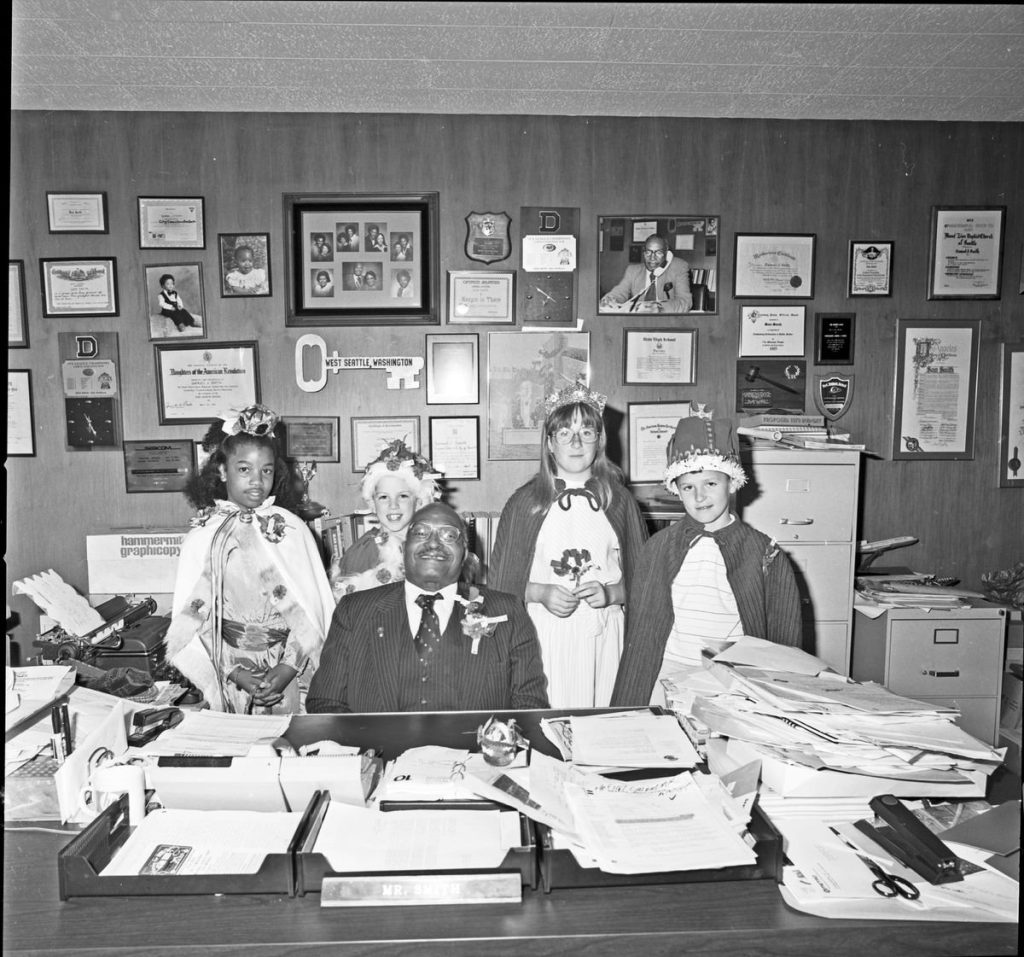

Sam Smith Apartments in Rainier Valley

SEED is focusing on multi-generational living, with a four-story, 50-unit building named for Sam Smith, a civil rights activist, former state legislator, and Seattle’s first Black city councilmember, soon to break ground. Only five of the units will be one-bedroom, while 25 will be two-bedroom units and 20 will have three bedrooms.

“We listened to the community, and [the] community was very clear,” said Michael Seiwerath, executive director of SEED. “They wanted rents at lower income levels and they wanted family-sized units. Multi-generational housing for new Americans and longtime residents.”

Seiwerath says that the final mix of income levels isn’t finalized, but nearly all units will be affordable for those earning 50% AMI or lower, with a few at 60% AMI or lower. “We’re trying to see how affordable we can make it, including getting some units down to 30% and 40% AMI when possible.”

The build has no retail on the ground floor in order to maximize the number of family-sized units.

Seiwerath notes that some affordable housing developers, in the rush to meet soaring demand, created smaller units, which can be built for less. This created a tension in some South End communities, he said. “They were very clear what their priority was, which is those larger homes. There’s just not that many, particularly three-bedroom apartments on the market at any price, let alone affordable.”

In particular, the Sam Smith complex is meant to create solutions for multi-generational families that may have children, parents, and grandparents or aunts and uncles living together. “We’re trying to see how we can be intentional with that,” he said.

SEED did a land swap with the city, for instance, to help them create Cheryl Chow Park – also named for a former Seattle city council member – that includes a playground, basketball courts, and picnic area with barbecues. The completely ADA-accessible park was designed specifically as a multi-generational gathering space.

Integral to SEED’s housing complexes are resident services teams, which provide each project’s ethnically diverse tenant population with advice on food security, affordable child care, rental assistance, and mental health services. “We’re very proud to have our resident services team, who are on staff, working daily to support our residents,” Seiwerath said.

SEED also works with East African Community Services to provide multi-lingual and culturally appropriate services to immigrant families at some of its complexes.

Seiwerath said the name for the final building in Rainier Court was an obvious choice.

“It’s going to be named after the late, great legislator Sam Smith, who worked at the city and state level to help end housing segregation,” Seiwerath said. “He was a proud community member of the South End and a proud champion of affordable housing.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.