Why does it take longer to complete a set of bus upgrades than it took to put a human being on the moon? A report commissioned by the King County Council and released this fall spells out a long answer to that question, pointing the finger at long permitting timelines, errors in pre-construction survey work, and delays from property acquisition as factors that have been holding back new RapidRide ribbon cuttings in recent years.

The report’s release comes at a time when the RapidRide program faces an uncertain future, with King County’s final 2026-2027 budget slashing the potential scope of the only RapidRide projects currently in planning, the K Line between Bellevue and Kirkland and the R Line though Seattle’s Rainier Valley.

Budget reductions reflect the worsening landscape of federal transit funding, on top of structural budget issues within King County Metro. Ultimately, they also show a de-prioritization of bus rapid transit projects at Washington State’s largest transit agency.

Girmay Zahilay, who was sworn in last week as King County Executive, has pledged to “fast track” the long-promised R Line during his term. But without addressing the issues that compound into the lengthy timelines that have become a feature of the RapidRide program as a whole, major transit upgrade projects will likely be few and far between, at least for now.

How a six-year project stretches to 10+

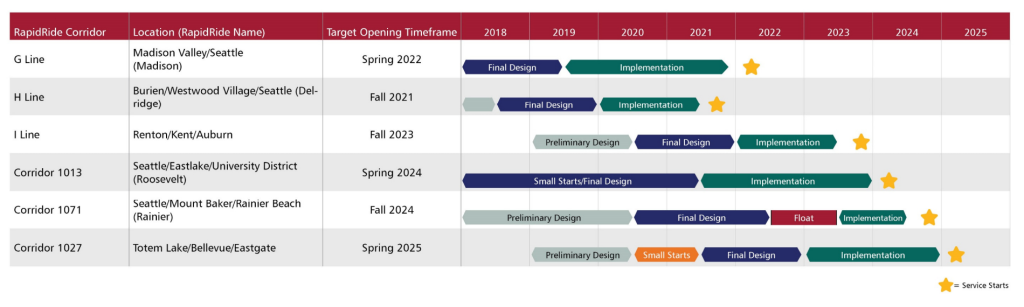

In 2018, King County Metro had six RapidRide projects in planning across the county, all of which were expected to open by early 2025. Only two of those lines, RapidRide H and G, are open now, with the R Line not expected to open until 2032 at the earliest. While some of the factors behind those delays — including the Covid-19 pandemic and a lengthy concrete workers’ strike — aren’t likely to repeat themselves, the report made it clear that RapidRide projects are vulnerable to long delays from a multitude of other causes.

“Despite employing a tactical approach that includes ongoing risk assessment and mitigation, RapidRide expansion projects have experienced multiple periods of schedule delay, not dissimilar to other infrastructure projects across the United States,” the report notes. “Identifying contributors to schedule delay and employing workable mitigation strategies are the responsibility of King County Metro, in coordination with jurisdictional partners, local utilities, contracted consultants and construction firms, and governing bodies where proposed legislation may be necessary.”

The report primarily looked at RapidRide projects developed by King County, including the H Line between Seattle and Burien that opened in 2023, and the I Line between Renton and Auburn that is set to start construction by the end of this year. But it did provide a glimpse at similar factors leading to delays on Seattle-led RapidRide projects, including the G Line (which had some very unique challenges when it came time to launch) and the under-construction J Line.

RapidRide H: initially planned for 2020 opening, actual opening date 2023

- Issues with station designs: 1 year delay

- Concrete workers’ strike: six-month delay

- Inaccurate as-built plan sets and inaccurate documentation of underground utilities: three-month delay

The biggest delay that impacted 2023’s H Line was a one-year delay that stemmed from King County’s “kit of parts” (KOP) station designs. Rolled out in 2019 and intended to streamline RapidRide construction by standardizing station designs, the kit of parts was supposed to save Metro time. But with the H Line being the first project the designs were implemented on, issues discovered with those designs — just as shovels were being brought out for the groundbreaking — added a significant amount of extra time.

“By May 2021, the H Line project team had identified specific issues with KOP design that would require correction prior to ordering and installing KOP for H Line stations, requiring delays,” the report reads. “The H Line team worked directly with the KOP fabricator to correct shelter gutter slope, wobble stabilization, lighting access, lighting power/angle, cladding joints, and map case dimensions, and to correct pylon key doors, electronics, and electrical box enclosures.”

The H Line also encountered an issue that has popped up again and again on RapidRide projects: conditions on the ground that differed from the contracted plans, including utility infrastructure that was found in unexpected places. Such issues delayed the H Line by three months, and later popped up on the G Line.

“In roadway construction projects, an understanding of existing capital improvements and underground utilities locations in the project corridor is essential to accurate project design and implementation,” the report states. “However, only after excavation has begun can the contractor and project team fully understand the extent of inaccuracies. Inaccurate as-built plan sets and inaccurate documentation of underground utilities locations that were identified throughout 2021 and 2022 excavation efforts [on the H Line] resulted in several months of redesigns and change orders.”

RapidRide I: initially planned for 2022 opening, current projected opening date 2027

- Delays getting to a baseline project cost estimate: 2 years of delay

- Design and permitting reviews by local jurisdictions: 1 year delay

- Property acquisition: 1 year delay

- Federal Transit Administration (FTA) grant coordination: 1 year delay

The RapidRide I, which will be the first line to operate fully outside the City of Seattle since the F Line in 2014, encountered even more delays than the H Line. It took two years longer than expected to simply get to a 30%, or “baseline” project estimate, partially (though not fully) because of Covid disruptions.

“Refinement of staffing capacities, establishment of predecessor bus route service, scoping for and contracting of consultant services, and COVID-19 pandemic impacts each contributed in smaller ways toward larger, cumulative delays between 2019’s assumptions and 2021’s estimates,” the report says. “The most significant of these factors were COVID-19 pandemic impacts, which contributed to and even introduced delay into some of the remaining factors.”

After getting to a new baseline, Metro ran into significant issues when it came to permitting its project with the cities of Renton, Auburn, and Kent, along with the Washington State Department of Transportation. “It became apparent throughout this process that Metro had underestimated the amount of time some jurisdictions would need to review design packages and the staff and management time it would require to resolve the quantity of comments toward completing design,” the report states.

Coordination with the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) also took much longer than expected, as this was the first time that Metro had been directly applying for grant funding through the agency’s Capital Investment Grant program, rather than relying on the City of Seattle to do that work. (The F and E lines received direct Congressional appropriation.)

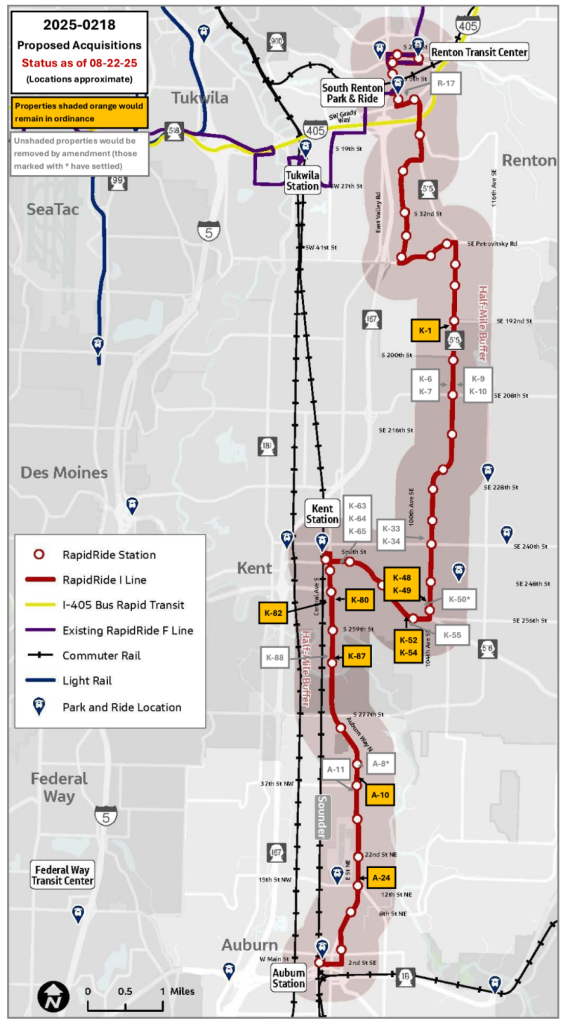

Finally, Metro ran into significant headwinds fully completing the property acquisitions needed to get the I Line into the construction phase, with a small number of property owners refusing to negotiate. Earlier this year, The Urbanist covered an eleventh-hour request that Metro made to the King County Council to unlock its condemnation authority to speed things along, a move that was ultimately granted after considerable back-and-forth.

The report also underscores the role the staffing capacity at Metro can have when it comes to keeping these projects on track. Authors note a six-month delay to the J Line, due to Metro’s inability to coordinate with the SDOT team working on the project.

“Due to a high number of staffing vacancies at King County Metro, existing staffing levels have not always had capacity to respond to design reviews and related project needs on the schedule requested by SDOT. This includes key disciplines, including trolley infrastructure, where subject matter expertise is required and where consultant expertise is often limited. This resulted in multiple and often compounded delays in moving project milestones forward in design and construction phases, ultimately impacting the overall project delivery timeline.”

Lessons already learned

After ultimately being able to deliver the H and G Line projects, Metro has already adopted some internal reforms that are intended to keep projects on track and not succumb to the same sources of delay.

“As part of assessing lessons learned from the G Line and H Line design phases, Metro increased its investment in utilities conflict mapping as part of the I Line design phase. This was done in response to the large number of unanticipated utilities discoveries on the G Line and H Line,” the report notes. “The increased investment on the I Line allowed for full-depth and full-width potholing of future pole locations on the project. This was done to better assess the feasibility of the proposed pole location. The I Line is set to begin construction in the 2nd half of 2025 and the project team will be monitoring to see if there is the expected decrease in unanticipated utilities discoveries.”

Metro isn’t the only one applying these lessons — the Seattle Department of Transportation, which is handling work on the RapidRide J and likely will be taking the lead on RapidRide R construction, has also made some adjustments to how construction work is managed.

“We applied several key lessons from the RapidRide G Line to improve efficiency and reduce risk on the J Line. This includes more extensive advanced potholing—especially at pole locations—to minimize utility conflicts and avoid delays with long lead-time materials. We also held risk workshops early in the project to build a more resilient schedule with contingency for differing site conditions,” SDOT spokesperson Mariam Ali told The Urbanist this summer, as J Line construction was well underway.

Ali also noted that SDOT has implemented stronger requirements for its contractor construction schedules, including “labor-loaded scheduling to better account for crew availability” along with other reforms, including advance coordination with Metro on trolley wire de-energization.

Reforms on the table

The report offers some potential legislative fixes that could be implemented to reduce delays on future RapidRide projects, but its conclusions are fairly limited — confined to the types of RapidRide projects that the agency has done in the past. At the top of the list are more binding agreements between the local governments involved in RapidRide permitting, something that really would have reduced delays on a project like RapidRide I that needed buyoff from four separate governments, all with competing policy priorities.

“Metro recommends that when investing in RapidRide, Metro and its partner jurisdictions should enter into Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs) that define project priorities, set mutual goals and commitments for both parties, help identify early in the project any significant risks, and can extend beyond fiscal year budgets,” the report states. “Such agreements would ideally be finalized prior to the start of the design phase, soon after the Locally Preferred Alternative (LPA) is adopted by the County Council, and the County Council would approve the agreement and the commitments made therein.”

Metro also proposes that the King County Council grant the agency the authority to acquire property “under the threat of condemnation.” That would give the agency an additional stick against property owners who are reluctant to negotiate with the County.

“Metro would still follow all federal, state, and local requirements for property acquisition and would use all reasonable efforts to acquire property rights through negotiated settlement,” the report notes. “However, the proposed ordinance would allow, but not require, Metro to use eminent domain, if necessary, after negotiations reached an impasse – an inability for both parties to agree to an outcome – without having to take each individual property to the County Council for review. The major difference would be in timing – granting the project the authority to use condemnation, if necessary, early in the project.”

Receiving condemnation authority without having to go to the legislative branch appears an unlikely outcome, as the process around I Line clearly illustrated. Not addressed is whether Metro can adjust RapidRide designs to minimize property acquisition, utilizing existing right of way instead. In part this is due to the requirements of FTA’s Small Starts grant program, where shelters and passenger information are requirements for every stop — but often opposition from local governments to reallocating road space means that private property becomes the fall back.

The future of RapidRide?

Tucked into the 2026-2027 budget approved by the King County Council earlier this month is a request for a follow up to this report, asking an even more salient question: what is the future of the RapidRide program? Given the fact that the program is clearly running on fumes, some change in strategy is likely warranted.

The proviso suggests a potential move beyond the corridor approach toward a systemwide one.

Specifically, it asks Metro to “identify opportunities to use a service-led planning approach that would prioritize capital investments in RapidRide or other very frequent service based on their ability to enhance speed, coordination, and convenience for a broad range of passengers, and to evaluate how targeted infrastructure improvements implemented systemwide could support fast, frequent, and reliable service without requiring full-scale corridor redevelopment, and to quantify the potential time and budget savings that could be achieved by implementing a more flexible, service-driven investment strategy.”

The fact that such a request made it into the budget is a hopeful sign, but it will ultimately fall to Executive Zahilay to establish what the RapidRide program’s next era will be. It’s possible the focus will stay on chasing federal dollars, likely leaving the program beholden to long timelines, or perhaps something new will emerge more focused on meeting riders sooner.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.