Washington’s third largest city is poised to tack on additional fees on homebuilders in mid-2026, following a 6-3 vote to adopt a new transportation impact fee framework at the Tacoma City Council on December 9. On track to go into effect next summer, the new fee structure is seen as a badly needed new source of revenue for transportation projects in the wake of the failed Streets Initiative II ballot measure last spring.

However, the idea of increasing the cost of construction just as reforms intended to increase housing availability and affordability in the City of Destiny, particularly the Home in Tacoma rezones, start to take effect has drawn opposition.

Impact fees on new development have been legal under Washington law for decades, approved as a method to fund transportation projects, add school and park space, and increase fire department capacity. That said, some of the state’s most populous cities have held off on implementing them.

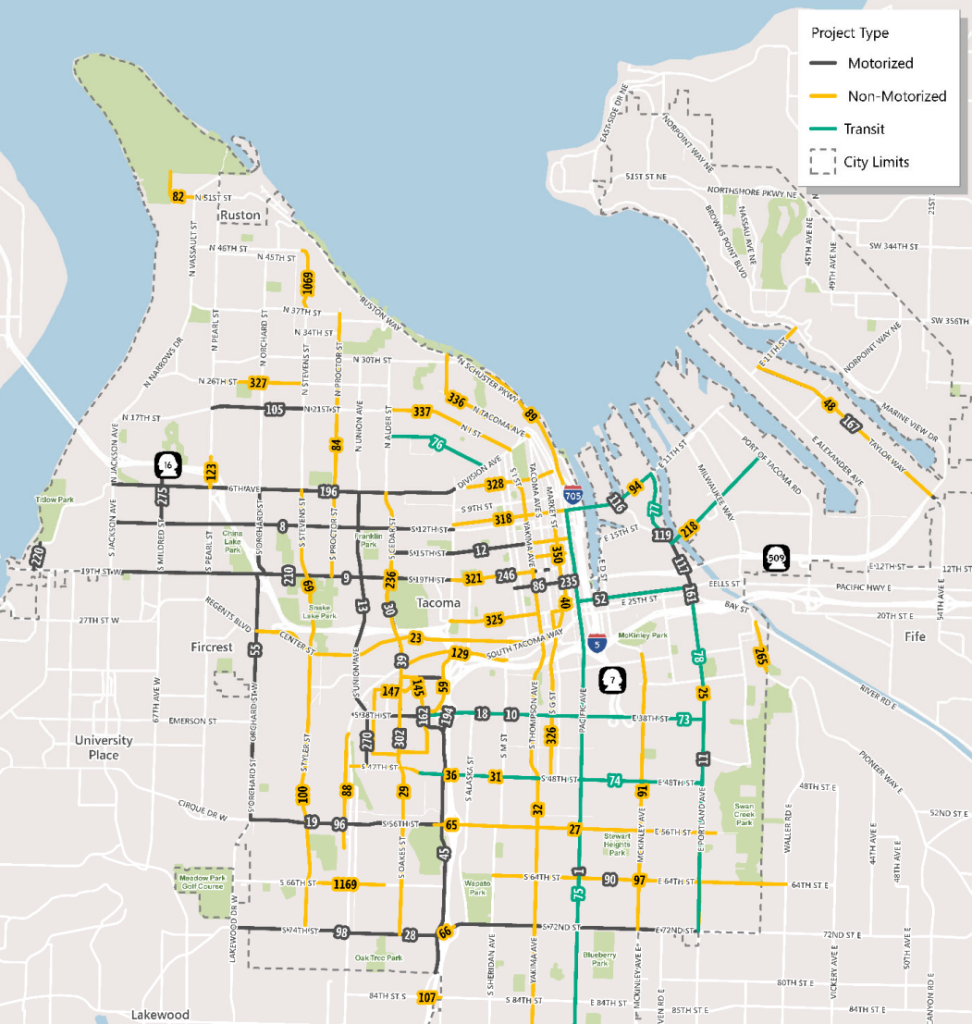

With the ostensible goal of ensuring that “growth pays for growth,” transportation impact fees can only be used to pay for upgrades that increase a transportation system’s capacity, and not to correct any existing deficiencies or basic maintenance. That capacity can come from new vehicle space, or from new multimodal facilities like protected bike lanes and sidewalks.

Tacoma is eyeing impact fees to pay for portions of long-planned street upgrades that would have a big impact on the ability for city residents and visitors to get around without a car, including pedestrian and bicycle upgrades to 6th Avenue through the busy 6th Avenue business district, and a protected bikeway on Tyler Street in South Tacoma. Transportation advocacy group Tacoma On The Go backed the impact fee plan, and encouraged allies to speak in support at Council.

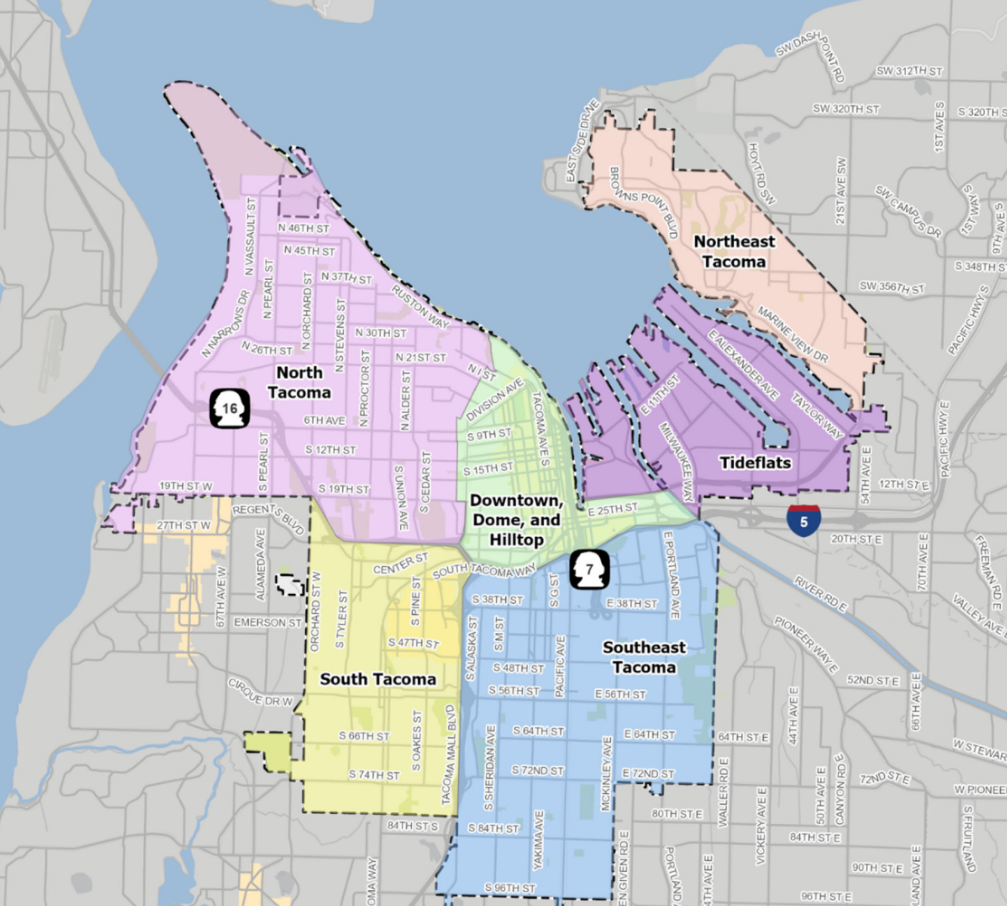

Unlike cities like Spokane, where an impact fee is levied based on the type of development planned — with denser housing projects charged less per unit than single lot projects or car-oriented retail uses — Tacoma’s new impact fee is blunter and varies only by the area of the city where a project is located.

Projects in North Tacoma will be charged $5,286 for every PM peak hour car trip that the City expects the development to generate, projects in South Tacoma will pay $5,208. Projects in the northeast quadrant of the city, near Federal Way, will only pay $764 per PM trip, due to the lack of planned transportation projects in that area of the city.

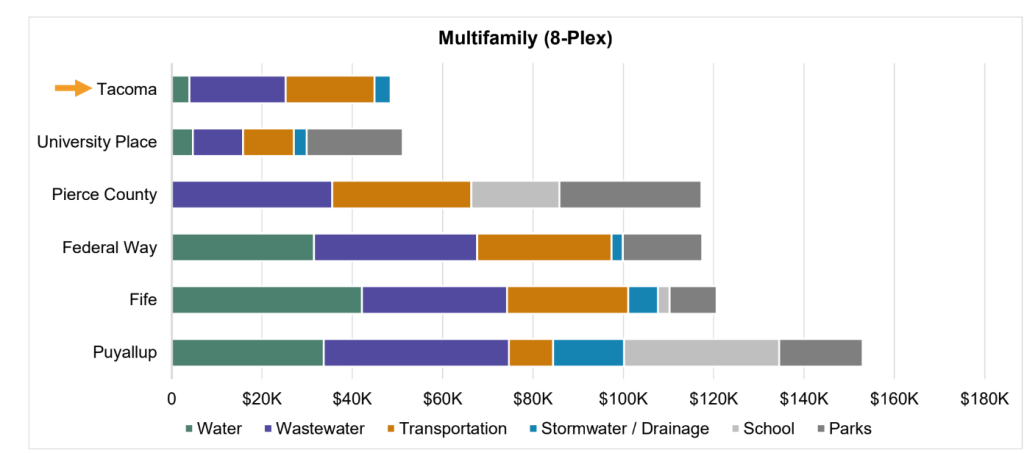

In defending the new fees, City leaders have been pointing to the fact that collectively, charges to build new multifamily development in Tacoma remain much lower than in nearby cities, including unincorporated Pierce County. Inclusive of all charges, including wastewater and storm water fees, a developer of a new eight-unit apartment building in Tacoma would be expected to pay around $50,000 after the transportation impact fee program takes effect, compared to nearly $120,000 in Pierce County and around $150,000 in Puyallup.

But even if the fees remain low by comparison to nearby cities, additional costs could make some housing projects within Tacoma infeasible, particularly during the current environment of high interest rates and increasing materials costs. As a city aiming to grow to 325,000 people in the next 15 years, a comparison to Fife will only go so far.

“We wanted to make sure that we weren’t making Tacoma’s fees enormously different than others, but we’re still coming in low on the graph there,” Councilmember Kristina Walker, who sponsored the proposal, told The Urbanist. “The other piece of this is that we are taking advantage of the development exemptions, specifically those for [transit-oriented development] and for affordable housing. So keeping an eye to that always, so that we continue to have especially affordable, transit-friendly housing built in our city.”

Under HB 1491, the transit-oriented development bill approved by the legislature earlier this year, Tacoma can authorize a 50% discount on impact fees within a half-mile of current and future rail stations, including the Tacoma Dome Sounder station, the T Line streetcar and its future extension to Tacoma Community College, along with a planned light rail station on Puyallup Avenue as part of the extension between Federal Way and Tacoma Dome. The City could authorize other exemptions, but under state law they would be required to make up the discount.

As co-chair of the Tacoma Transportation Commission, Matt Stevens had a front row seat for the development of the impact fee program, with meetings taking place on the topic between 2021 and 2025. He credited the City with taking out its pencils and developing a program that was more attentive to concerns around adding costs to housing, an issue that was also raised by Tacoma’s Permit Advisory Task Force.

“I would say that the Transportation Commission was very concerned with the initial proposal,” Stevens told The Urbanist. “I will commend the City, they did a lot of drafts to evaluate this. Because the improvements are the most needed in the historically disadvantaged south end and the Eastside, additional bedrooms — which which translate to additional trips — the more improvements we did in those areas, means it was going to cost a lot more. And so the city did a lot of analysis to understand that: how do we make it so it’s much more equal across the city, so that those areas that’ve been historically under-invested in, that they’re not having to pay for so much more, when they’re already on a much lower level on the scale.”

But that work apparently didn’t go far enough for three councilmembers, with concerns raised ahead of the final vote on both the impact of higher fees on housing but also potential legal risks to the city.

Councilmember Sandesh Sadalge, who opposed the ordinance, brought up the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision Sheetz v. County of El Dorado as creating a potential risk to the city’s new program. A challenge to a local impact fee program in Colorado, the Supreme Court didn’t overturn the ability of local governments to collect impact fees, but did rule that such fees are required to have an “essential nexus” to a legitimate government interest and be “roughly proportional” to the impact of planned development.

“Transportation impact fees are kind of similar to tariffs — developers aren’t paying these. The end users: the renters, the triple-net lease on a commercial property, or homeowners, will eventually pay this,” Sadalge said. “But recent federal court cases have shown that there is an opportunity now for those developers to come back within 10 years and sue us and get that money back due to the nexus and proportionality requirement. I think right now, where we have both offsite improvement requirements on developments, plus this idea of nexus and proportionality, plus this fee on top of it, not only does it add a barrier, it is creating a legal liability where we’re just going to end up giving this money back eventually.”

Deputy Mayor Kiara Daniels, who left office at the end of 2025 after declining to run for an additional term on the council, honed in on the issue of looking holistically at how costs get added to housing, a basic need that everyone agrees should be more affordable.

“I’ve spent the last four years advocating for housing in this community, housing affordability, and I feel like we are neglecting some really hard conversations about what that looks like and what it really means to not just think about the regulation of housing, but also the supply of housing and how we balance that with our environment and our infrastructure,” Daniels said.

While wholesale reform of how local governments, especially under-resourced cities like Tacoma, fund transportation improvements is surely overdue, a broad swath of the city’s multimodal transportation advocates see the impact fee program as a positive step, at least in the context of the tools that are available.

“The goal here is to mitigate for more trips and continue the city’s vision of making it easier to walk bike and transit both for safety reasons, but also in terms of quality of life and helping people get around the city no matter mode what they’re on,” Walker said. “This is not separate from all our other transportation work. It’s built-in, based in Vision Zero and safety and equity.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.