Washington’s second-largest county cut health department jobs and continues to lag in transit service.

For Pierce County, Pierce Transit, and the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, it’s a new year, a new budget — but the same problems. All of these entities face serious financial hurdles, leading to layoffs, lagging service levels, and reduced program offerings.

Despite a balanced budget this biennium, Pierce County officials are facing the very real possibility of long-term struggles that could severely impact the County’s main focus areas, including public safety and affordable housing. Officials are worried that the federal government will slash local funding, and the County’s limited options for raising revenue could make dealing with a fiscal crisis particularly difficult.

Pierce Transit, on the other hand, is dealing with financial woes that began nearly 15 years ago. Its budget is only a fraction of what’s needed to meet demand for transit and offer service at comparable frequencies to its peer agencies.

The health department, also an independent entity, has this year faced a major budgeting setback largely driven by total loss of Covid-19 funding, less overall grant funding, and a decrease in Foundational Public Health Services funding. As a result, it had to cut 22 staff jobs, some of which came from program divisions.

Pierce County

Let’s start with the overall county budget. Pierce County budgets for bienniums, or two-year intervals. This means that the budget the county council passed in late November represents the County’s funding plans through 2027. In 2027, it will prepare to pass another two-year budget.

This year, the County passed a $3.5 billion budget. That budget, said County spokesperson Connor Davis, “reflects both optimism and realism—optimism about investments that will make the County safer, healthier, and more connected, and realism about the long-term fiscal challenges we must solve.”

He noted that the County budgeted a modest 2% over last biennium’s budget, and prioritized minimizing risk while fulfilling the County’s essential obligations, keeping vulnerable individuals safe, and progressing on strategic priorities.

Priorities

At the top of the County’s priority list is public safety, Davis said. Nearly 80% of the General Fund went towards services like the Pierce County Sheriff’s Office, the prosecutor’s office, and Superior Court.

More than half of that funding went towards the sheriff’s department. The council has also planned to match the sheriff’s department’s funding requests, after Mello concludes contract negotiations with the Pierce County Deputy Sheriff’s Guild, the guild that represents management staff.

These negotiations have been ongoing for more than a year, and have entered into interest arbitration.

Davis also said the County is prioritizing affordable housing, as well as investing in behavioral health services and creating safer transportation infrastructure.

Long-term Projections and New Revenue

The law limits what the County can use as a revenue source. Its primary sources of revenue are property taxes and sales taxes, and for the next three years, the County’s financial reserves are projected to remain in the black. But that could swiftly change, particularly given the combination of threats of funding cuts coming from Washington, D.C., existing state and federal cuts, and the fact that revenue coming from these taxes just isn’t keeping pace with the rising cost of County employees’ salaries and benefits, and core County services.

“This imbalance, combined with state and federal budget cuts, has created a structural deficit for Pierce County,” Davis explained. “Projections show [County] reserves falling below recommended levels in later years. The County maintains lean staffing compared to our peers and we have implemented cost-cutting measures, including a hiring freeze for positions supported by the General Fund. Without new, stable funding sources, the County will face difficult tradeoffs in the future.”

One of the new revenue sources the County is considering is imposing a 0.1% local sales tax to fund public safety, as authorized in House Bill 2015, which the legislature passed last year. In Pierce County, Davis said, this tax would generate more than $27 million for public safety over time, increasing overall public safety funding by 4%.

Last autumn, the County convened a Public Safety Work Group to figure out a plan for this tax, if the Pierce County Council approves it. The group consisted of Mello, the Department of Assigned Council, the District Court, the Juvenile Court, the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, the Pierce County Sheriff’s Office, and the Superior Court.

The group’s submission of the ordinance has been delayed, Davis said, and the Pierce County Council has not yet set a date to discuss it.

Transportation

Unlike in King County, Pierce Transit — the main transit agency in Pierce County — isn’t under County control. Even so, the County does have the ability to create transportation-related projects, funded through a mix of County, state, and federal money.

This biennial budget’s focus on public safety also extends to transport, Davis said, particularly as it relates to making the area safer for drivers, pedestrians, and bicyclists.

Davis highlighted a few projects, including the recently adopted Vision Zero Action Plan. The plan is meant to eliminate fatalities and serious injuries on County roadways by 2035. The County also partnered with local school districts in unincorporated Pierce County on its Safe Routes to School initiative, which focuses on creating safer walking routes to school by prioritizing sidewalk improvements in specific areas.

He also pointed to the ongoing Blue Zones Parkland-Spanaway project, which is supposed to create healthier communities through a number of community-based improvements, including improving transportation infrastructure between Parkland and Spanaway.

The County recently updated its Transportation Improvement Program to include tags specifying when work relates to any of these three initiatives.

Pierce Transit

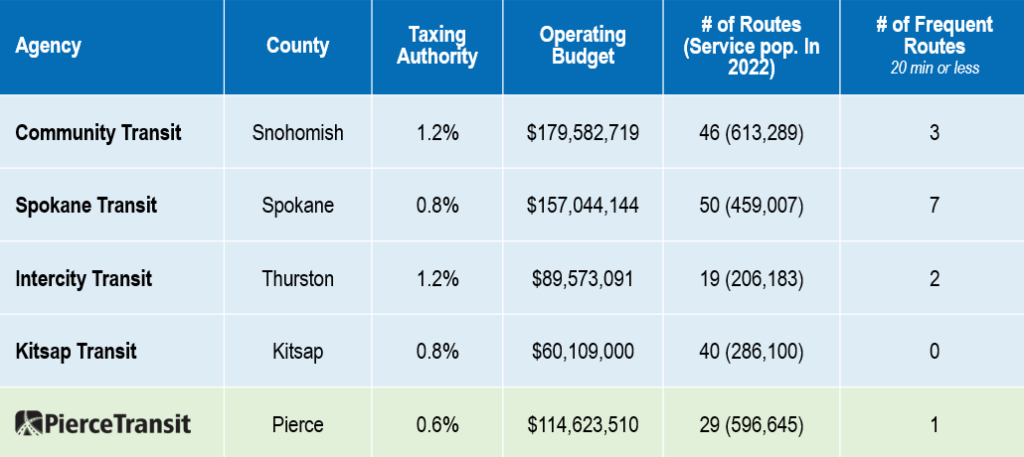

Pierce Transit has historically lagged behind its peer agencies in the amount of service it can provide. The number one reason for this, said Pierce Transit spokesperson Rebecca Japhet, is lower funding levels. (Japhet retired from Pierce Transit shortly after speaking with The Urbanist.) More than three-quarters of the agency’s budget comes from a 0.6% local sales tax. That’s the lowest sales tax percentage collected amongst Pierce Transit’s peer agencies, and it hasn’t changed for the last 23 years.

Moreover, Pierce Transit is a standalone Public Transportation Benefit Area (PTBA). It’s not part of Pierce County. Putting aside the fact that King County Metro is part of King County, when Pierce Transit stands in comparison to King County Metro’s budget, it’s no contest: King County Metro has an annual budget of about $2 billion to serve its 2.4 million residents, while Pierce Transit has just north of $224 million to serve about 950,000 residents.

In other words, King County spends 3.5 times as much on local transit per capita as Pierce Transit.

King County also has its RapidRide enhanced bus network and plans to add new lines. In contrast, Pierce Transit has just one frequent route that runs every 20 minutes or less.

But the agency would like that to change, and plans to make changes as soon as funding allows. Japhet said that Pierce Transit spent 2024 and 2025 gathering community feedback about what they want from local transit — more service on weekends, more frequent trips, and trips earlier and later in the day. From that, Pierce Transit developed an updated Long Range Plan.

Now, the agency is creating a framework to provide more service, in line with that plan, should funding become available. While it did not commit to a higher level of sales tax, Japhet said that more funding “could” come from a higher sales tax that voters would have to approve. The agency is also looking at other revenue sources, such as grants.

Pierce Transit spokesperson Penny Grellier said grant revenue could fund bus shelters, transit centers, and maintenance facilities, as well as bus replacements. She added that operating grants are available for services like Paratransit or the Pierce Transit Runner, though these are usually one-time grants or represent limited funding.

Pierce Transit’s 2026 budget includes funding for a few additional services inside its service boundaries. These new services will start in March, and will include an extended Stream Community Line to Commerce Street Station in downtown Tacoma. It will also increase service on two different routes, Route 1 and Route 3, so that a bus arrives every 15 minutes between 6 a.m. — 7 p.m. on weekdays.

Route 1 runs on a 30-minute schedule starting at 4 a.m., and changes to a 15-minute schedule just before 9 a.m. It returns to a 30-minute schedule just before 6 p.m., and stops service at 11:30 p.m.

Route 3 runs similarly, on a 30-minute schedule at the start of service at 5:30 a.m. until 10 a.m., after which it switches to a 15-minute schedule until 6:30 p.m. After that, it changes back to a 30-minute schedule, until the end of service at 10:30 p.m.

Japhet highlighted, too, that the challenges that Pierce Transit faces are not entirely new. The agency has a limited range, and some parts of the county are located outside its current service area. This includes places like the Key Peninsula, a largely unincorporated area located just to the west of Tacoma across Puget Sound that is home to two state parks.

This limited service stems from past financial troubles. In 2011, following declining revenues, the agency’s board of commissioners convened a Public Transportation Improvement Conference to address the issue through revisions to the PTBA boundaries. One official from each jurisdiction in Pierce County had the authority to decide whether their jurisdiction would withdraw from the PTBA.

In 2012, the cities of Bonney Lake, Buckley, DuPont, Orting, and Sumner chose to leave the transportation benefit area. Pierce County also voted to remove a large portion of unincorporated Pierce County, including the Key Peninsula.

Today, Pierce Transit services 70% of Pierce County. Japhet said that Pierce Transit is aware of the challenges facing particular areas, and is “always open to providing contracted service, should another organization provide funding to do so, and Pierce Transit has the resources (drivers, vehicles, etc.) available. This would require an organization paying for 100% of the service costs, since it would be outside Pierce Transit’s service area.”

She also noted that rural areas have lower ridership, which makes service to those areas more expensive to operate. Because routes are evaluated on their efficiency, it’s hard to justify serving rural locations that are further apart, since the low ridership means that the agency is spending more to move fewer people from place to place.

As far as the Key Peninsula goes, she said, the agency “continues to engage with elected officials and community leaders about how we can support transportation solutions for Key Peninsula. For example, we have coordinated with those planning the new pilot service to ensure riders can make easy connections to Pierce Transit service, once they are into our service area.”

Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department

It’s not just Pierce County and Pierce Transit that are feeling the squeeze. The Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department (TPCHD) — which currently faces a biennial budget reduction of a whopping $24 million — recently made headlines after cutting 22 staffers.

TPCHD spokesperson Kenny Via told The Urbanist that the staffing cuts were lower than what was originally on the table. At first, he said, the board presented a budget in July 2025 that would have meant 40 people lost their jobs. But between then and budget deadline time, the agency was able to secure enough funding to save 18 of those jobs by both finding new funding sources and deferring hiring for open positions. He also said that the department put a voluntary retirement incentive in place.

Of the 22 positions cut, 12 were from the department’s administrative division. Those staffers originally supported program staff.

When asked how those 12 individuals’ work would be distributed, Via said that they came from “a wide range of support duties, including communications, finance, human resources, information technology, office administration, and records management,” and that the department is in the process of adjusting work in those programs and redistributing some duties, while ending others.

Of the remaining 10 who lost their jobs, six were from the agency’s Disease Prevention and Management Division. These staffers focused on STI/HIV programs, as well as the department’s Chronic Disease Prevention and Management and Immunizations and Provider Engagement programs.

Two more were in the TPCHD’s Strengthening Families Division. These staff members worked in the agency’s Parent, Child & Family Health program and Behavioral & Emotional Health program.

The last two came from the department’s Environmental Health Division, and worked in its Social, Economic & Environmental Conditions for Health program.

“We prioritized keeping positions that work to bring services directly to Pierce County residents,” Via said. “Because of this, we don’t expect the public to see any immediate impact on the services we provide.”

He noted that the agency has five open positions, three of which it is currently looking to fill.

Overall, the agency’s 2026-2027 biennial budget is $102.9 million, which represents a decrease of more than $24 million from its current budget. That decrease reflects a combination of changes to federal and state funding, Via explained, including decreased funding to Foundational Public Health Services, less grant funding, and a complete loss of Covid response funding.

The agency has a variety of revenue sources, but most of the TPCHD’s revenue comes first from permits and fees (39%), and then from the state (30%). It receives further funding from the County, federal government, private, local and miscellaneous funding, and the City of Tacoma.

Via noted that though the TPCHD had planned a certain budget, and that the county council had approved that budget, “things often shift over time. That will certainly be the case here as well. We usually amend our budget twice every year, in the spring and fall, with the most up to date information.”