A broad array of transit advocates are asking King County Executive Girmay Zahilay to put forward a funding measure to boost investments in countywide transit service this year. The request is a tall order, and would require intense coordination with Seattle, where local leaders are currently developing the next iteration of a city-specific transit funding measure set to expire in early 2027.

With King County Metro facing structural budget issues that are likely to result in a fiscal cliff early in the next decade, and bus service across the county still trailing pre-pandemic levels, a group that includes Transportation Choices Coalition, the Nondrivers Alliance, and Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587 argue that now is the time to utilize additional funding tools in the county’s toolbox. Tuesday’s letter urges Zahilay to consider utilizing the ability to leverage its already-established transportation benefit district, which could fund transit via a vehicle license fee or a sales tax increase up to 0.3%.

“As transit riders and activists we are concerned about transit funding in King County. We are facing an impending fiscal cliff and national economic downturn which will simultaneously increase the need for transit while reducing its funding,” the letter read. “As our country and region face a retracting economy, it is important to fulfill the affordability mandate voters resoundingly endorsed in the 2025 elections. Car dependency puts a financial burden on families and limits access to economic opportunity. Our transit network deserves investment, especially in South King County. A fully-funded transit system is crucial to meeting these needs.”

The full list of signers to the letter also includes the Seattle Transit Riders Union’s bus and transit service subcommittee, Move Redmond, Urbanist Shoreline, Livable Kirkland, Eastside Urbanism, West Seattle Urbanism, Complete Streets Bellevue, and Seattle Subway.

Passing a supplemental funding source to directly fund expansion of King County Metro service, building upon the 0.9% sales tax that the agency depends on for the lion’s share of its funding, has been a goal of transit advocates in King County for years. In 2014, county voters rejected a 0.1% sales tax increase paired with a $60 vehicle license fee that would have brought in at least $135 million per year, despite the threat of service cuts prompted by the Great Recession.

That failure at the ballot box prompted Seattle to go it alone with a successful ballot measure that averted many of those cuts, and turned the city into a major source of funding for bus service.

In 2020, it looked like King County might finally return to the ballot to take the momentum gained by Seattle’s measure countywide, but the COVID-19 pandemic put the kibosh on that idea. Seattle’s measure was scaled back later that year, something that advocate saw as a missed opportunity given the landslide 60-point margin it won by. Today, Seattle’s measure funds around 140,000 annual Metro service hours, compared to nearly 350,000 in 2019.

Since the Seattle Transit Measure is expiring at year’s end, 2026 is the next opportunity to bring the two levels of government into alignment, but with Zahilay and Seattle Mayor Katie Wilson still getting situated in office, it would require significant legwork. That said, improving bus service was one’s Wilson’s stated top priorities, and she did lead Transit Riders Union for over a decade before running for mayor.

“We are coming off the heels of a legendary year for transit in Puget Sound history. We just opened three new light rail stations, and we just elected an Executive who ran on a very heavily pro-South King County services platform,” Transit Riders Union member Noah Williams told The Urbanist in explaining this push. “It’s really important that we have a measure that offers truly regional freedom for all of King County. We have the Seattle transit benefit district here, which is great and provides funding for this local area. And there’s also been murmurs of transit benefit districts in a similar style appearing on the Eastside. It’s great that there’s the energy there. We believe that that should cover the whole region, not just Seattle.”

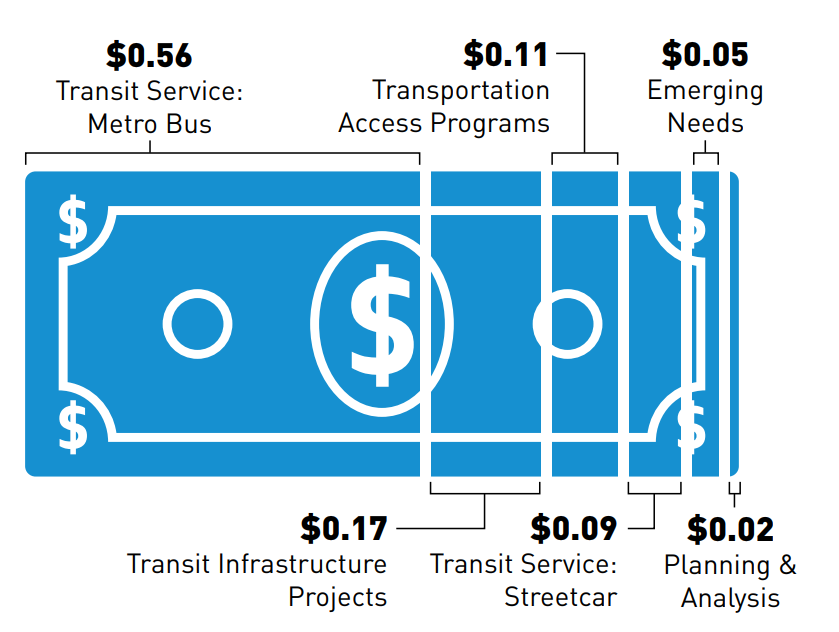

Seattle’s 0.15% sales tax measure currently funds way more than just bus service. Only around half of the approximately $50 million generated annually goes directly to Metro, with the remainder of the funds spent on physical improvements that benefit transit riders, keeping the Seattle Streetcar operating, free ORCA transit cards for underserved communities, and other policy priorities including City staff working to advance Seattle’s next Sound Transit lines. Last year, the measure was amended — under a proposal spearheaded by Councilmember Rob Saka — to allow spending on investments improving transit safety and security.

Though Wilson has signaled that she’s interested in pivoting the Seattle Transit Measure back toward the core goal of improving bus service, it’s unlikely that a county measure would be able to fund all of the programs on Seattle’s wish list.

Some signs of movement at the county level have emerged when it comes to additional transportation funding, even before Zahilay took office. On the campaign trail, both leading county executive candidates voiced support for putting a county transit measure on the ballot — though they didn’t specify timing.

Last summer, the County Council explored pulling the trigger on its ability to unlock 0.1% of the 0.3% in sales tax authority it has available, with the funds generated split between the county’s roads department and Metro. While the need for roads funding is relatively straightforward, with the county facing a significant roads funding crisis that could fully deplete its capital reserves within a few years, the exact uses for the new dollars at Metro were much less clear, and the idea was pulled back to the council’s backrooms.

That additional sales tax would have come on top of a 0.1% increase the county approved last year to fund public safety, an amount that was matched by many cities including Seattle. Double-dipping into sales tax authority would likely be seen as a major increase in regressive taxation, at a time when many progressive groups are trying to push to make the state tax code less regressive. But the universe of tools available to local government is very limited under state law, King County even more so than the City of Seattle.

The timeline for Wilson and Zahilay to coordinate on a paired strategy is tight, with the City likely to be finalizing its renewal measure by spring. In order to get on the November ballot, any measure would need to be approved by early summer.

“What we’re looking for is just to raise the floor of transit,” Transit Riders Union member Harper Nalley told The Urbanist. “Right now South King has decent service given the density and the character of that area, but it could do a lot more. Comparing South King [County]’s ridership to other cities, it’s much higher per capita. And so there’s definitely a need for it and a desire for it. And then Seattle, of course, has an even more open transit environment politically, and every measure has passed much with much wider margins in Seattle, and so we’d like to use that to be able to give [riders] the exceptional transit that Seattle really deserves.”

The Urbanist reached out to Executive Zahilay’s office on Thursday for comment and will update the piece if we hear back.

While opposed to a county transit measure in 2023, Zahilay told The Urbanist in December of 2024 when rolling out his county executive campaign: “My position that public transportation is a top priority and needs to be funded has not changed, but the level of emergency has changed, and that is that Metro is about to hit a fiscal cliff. There might be many people around the region who won’t be able to access public transportation, and I would want to give voters that chance of saying, ‘hey, we do want to fund Metro.’ And so I would give voters that option.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.