A bill paving the way for smaller, less expensive elevators was approved by the Washington State Senate late last week in a refined form. The 41-7 vote brings renewed hope for a nation-leading proposal to jettison overly restrictive standards for elevators that increase building costs and oftentimes lead to fewer elevators being built in the first place.

A similar, but more direct attempt at state building code reform died abruptly last year.

SB 5156, sponsored by Senator Jesse Salomon (D-32, Shoreline), has been significantly revamped after running into opposition in the state House in 2025. While the version greenlit by the Senate’s housing committee last year had included explicit direction to the state Department of Labor & Industries to revamp standards for elevators, the new version instead directs the state’s building code council to tackle the issue as part of their 2027 code update. In a compromise, the bill still includes explicit language to legalize smaller elevators that still meet the federal minimum for accessibility in buildings with up to 24 units or six stories.

It’s that provision that is the heart of the bill, creating an incentive for builders to stack units on top of one another without having to spring for a full elevator or being pushed to build no elevator at all. The change is meant to build on other reforms approved by the legislature in recent years, including another major change already being considered by the building code council that would legalize Seattle’s wildly successful single-stair regulations across the entire state.

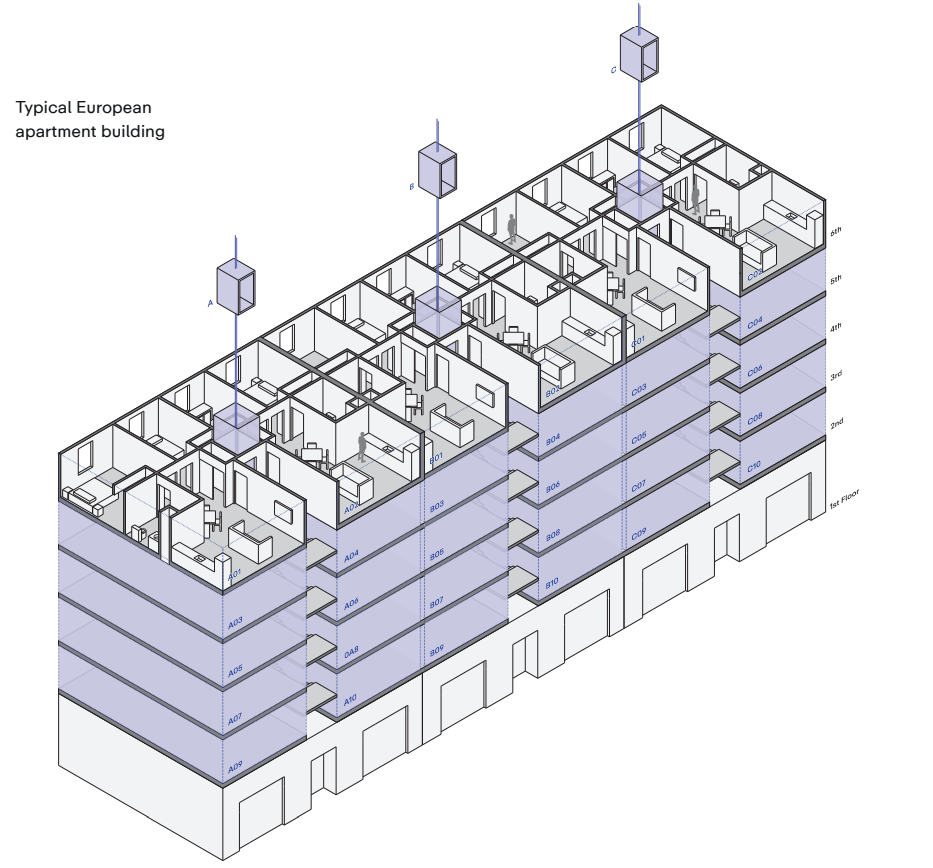

“This is a bill that I think fits within the abundance agenda that you hear about so commonly. This is an innovation in housing to go along with the bill that we passed a few years ago allowing single-stair apartments on single lots,” Solomon said on the Senate floor Friday. “This bill is a supplement that says that in these smaller apartment buildings, you don’t have to have a gigantic elevator like we require now in the United States. In Europe, they have smaller sized elevators.”

Regulations unique to the U.S. and Canada that tightly clamp down on what elevators look like and how they can be maintained are increasingly attracting notice in the housing reform world. In 2024, the Center for Building in North America released a 122-page report detailing the factors that force elevators in North America to be much more expensive — and rare — than in other parts of the world.

“The price to install an elevator in a new mid-rise building in the United States or Canada is now at least three times the cost in Western Europe or East Asia. Ongoing expenses like service contracts, periodic inspections, repairs, and modernizations are just as overpriced,” the report noted. “High-income countries with strong labor movements and high safety standards from South Korea to Switzerland have found ways to install wheelchair-accessible elevators in mid-rise apartment buildings for around $50,000 each, even after adjusting for America’s typically higher general price levels. In the United States and Canada, on the other hand, these installations start at around $150,000 in even low-cost areas.”

One major factor behind that disparity: U.S. elevators are required to be large enough to accommodate a full-sized stretcher for emergencies. In contrast, elevators elsewhere in the world are only required to accommodate a seated wheelchair user. But another major component is the incredibly limited elevator installation and repair market, which essentially operates as an oligopoly across North America and pushed back on reforms that could ultimately result in more elevators being built.

Last year, the union that represents those mechanics came out against SB 5156, with Lindsay LaBrosse, business representative for IUEC Local 19, asserting that the proposal would be “skirting important safety requirements.” Those concerns played a big part in the proposal being shelved, despite the fact that the U.S. is not a world leader when it comes to elevator safety. However, those same groups are likely to represent the biggest hurdle to the bill’s other provisions: asking the building code council to look at aligning Washington’s elevator regulations with global standards, a move that would be a sea change for any U.S. state.

“It shall be the intent of the state building code council and the department of labor and industries to support national and international standards harmonization efforts in order to foster the most competitive elevator sector possible, improve the affordability of elevators, and minimize modifications to model codes that increase costs,” the text of SB 5156 states.

According to Stephen Jacob Smith, the Center for Building in North America’s Executive Director, the reforms Washington is considering could unlock tens of thousands of dollars of savings for a small apartment building, especially if the building code council is able to make headway on costly requirements to include two-way video screens in every elevator.

An issue that few people were talking about in the housing space just a few years ago, elevator reform even made it onto the City of Seattle’s official legislative agenda for 2026, thanks to an amendment from Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck approved in December.

“This [bill], it maps really well to what we’ve been trying to do with the Comprehensive Plan, when we’re talking about a stacked flat strategy, really empowering and making sure that we are able to have more middle housing that allows for aging in place by making it easier to have more elevators go into middle housing options,” Rinck said in explaining how SB 5156 would supplement Seattle’s newly approved housing reforms.

The path for SB 5156 through the House won’t necessarily be a cakewalk, but the changes made to the bill since last year seem to have placated opposition within the Democratic caucus. Last year, Senators Javier Valdez (D-46th, Seattle), Tina Orwall (D-33rd, SeaTac), and Vandana Slatter (D-41st, Redmond) — legislators not known for maverick stances — voted against the bill on the Senate floor. But with the changes made this year, all three changed their position and voted yes.

Whether the bill is able to make it across the finish line this year or not, it’s clear that overhauling Washington’s outdated elevator standards is an issue that won’t be going away any time soon.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.