Throughout the development of the Washington State Convention Center (WSCC) expansion, the WSCC has repeated in marketing materials and public meetings that the project would be funded by existing taxes and no new taxes would be needed. However, very quietly, the WSCC also lobbied the state legislature for an expansion of the lodging tax to support the ever-expanding budget for this project. That lobbying effort bore fruit with the recent passage of HB 2015, which expands the current lodging tax (7% in Seattle, and 2.8% elsewhere in King County) to include hotels that have fewer than 60 rooms, as well as short-term rentals like Airbnb, both types of lodging that were previously only subject to regular sales tax.

The WSCC has been pushing for the tax increase since at least the 2016-2017 legislative session, after the project budget was increased from $1.4 billion to $1.6 billion. Another project budget increase of $100 million came earlier this year, and much of that latest increase was tied to the agreement with the Community Package Coalition, which would provide lump sum payments to community groups for projects such as Freeway Park improvements, a study to lid I-5, and payments for affordable housing (the largest piece of the package). During a Seattle City Council Sustainability and Transportation Committee meeting presentation, project developer Matt Griffin indicated the tax increase allowed for faster payments to the priorities of the Community Package, most notably toward affordable housing.

After those lump sums are paid, the future additional tax revenue would go directly to the WSCC. The WSCC desperately needed this agreement in order to convince the Seattle City Council that it would provide an appropriate public benefit to offset the negative impacts of five street and alley vacations (sales of publicly held rights-of-way). Prior to the agreement with the Community Package, the WSCC had struggled to show any public benefit worthy of the sale of valuable downtown streets and alleys.

HB 2015 indicates that the legislature is attempting to equalize taxation across all lodging types, but fails to acknowledge that different types of short-term lodging can serve vastly different populations. KUOW recently reported on how many small motels on Aurora Avenue in North Seattle serve as temporary homeless refuges with payments coming from either the homeless guests themselves or vouchers provided by service organizations. The guests of these small motels, (including both motels featured in the KUOW story) will soon face a significant increase in cost through the lodging tax, essentially taxing many who are struggling with homelessness to help pay for the convention center’s commitment to affordable housing.

While those staying in a hotel or motel after losing permanent housing are not counted in most statistics related to homelessness, King County’s 2017 Count Us In survey identified 5% of respondents previously lived in hotels or motels immediately prior to experiencing homelessness. Additionally, according to data collected by the Washington State Office of the Superintendant of Public Instruction (OSPI), over 500 homeless students in King County school districts relied on shelter in hotels or motels at some point during the year, due to lack of alternate housing. These small, older motels, which are not always the best housing option available, often serve as a last resort before living on the street. The increased tax base hits a portion of the population that doesn’t neatly fall into the “out of town” revenue sources that the lodging tax is supposed to tap.

Through the maneuvering of Seattle’s City Council last fall, the WSCC will not see revenue from the recently enacted short-term rental tax in Seattle. Seattle’s tax is going directly to affordable housing and community development initiatives without the WSCC as middleman. Perversely though, outside of Seattle, short-term rental guests in King County (think North Bend, Federal Way and Woodinville) will pay more to fund the expansion of the WSCC’s downtown Seattle facility and the Community Package than short-term rental guests in close proximity to the facility.

The WSCC has argued that short-term rentals have been drawing business away from traditional hotels and have hurt the lodging tax revenue that goes directly to the WSCC, necessitating the tax expansion. A quick look at WSCC annual reports show that from 2011 to 2016 (the same years that saw the rise of Airbnb and other vacation rental services) lodging tax revenue has grown from $48 million, to more than $77 million, a 60% increase. The tax revenue given to the WSCC has grown dramatically over the past five years, despite attendance remaining flat for the past 20 years even after major expansions doubled the size of the facility.

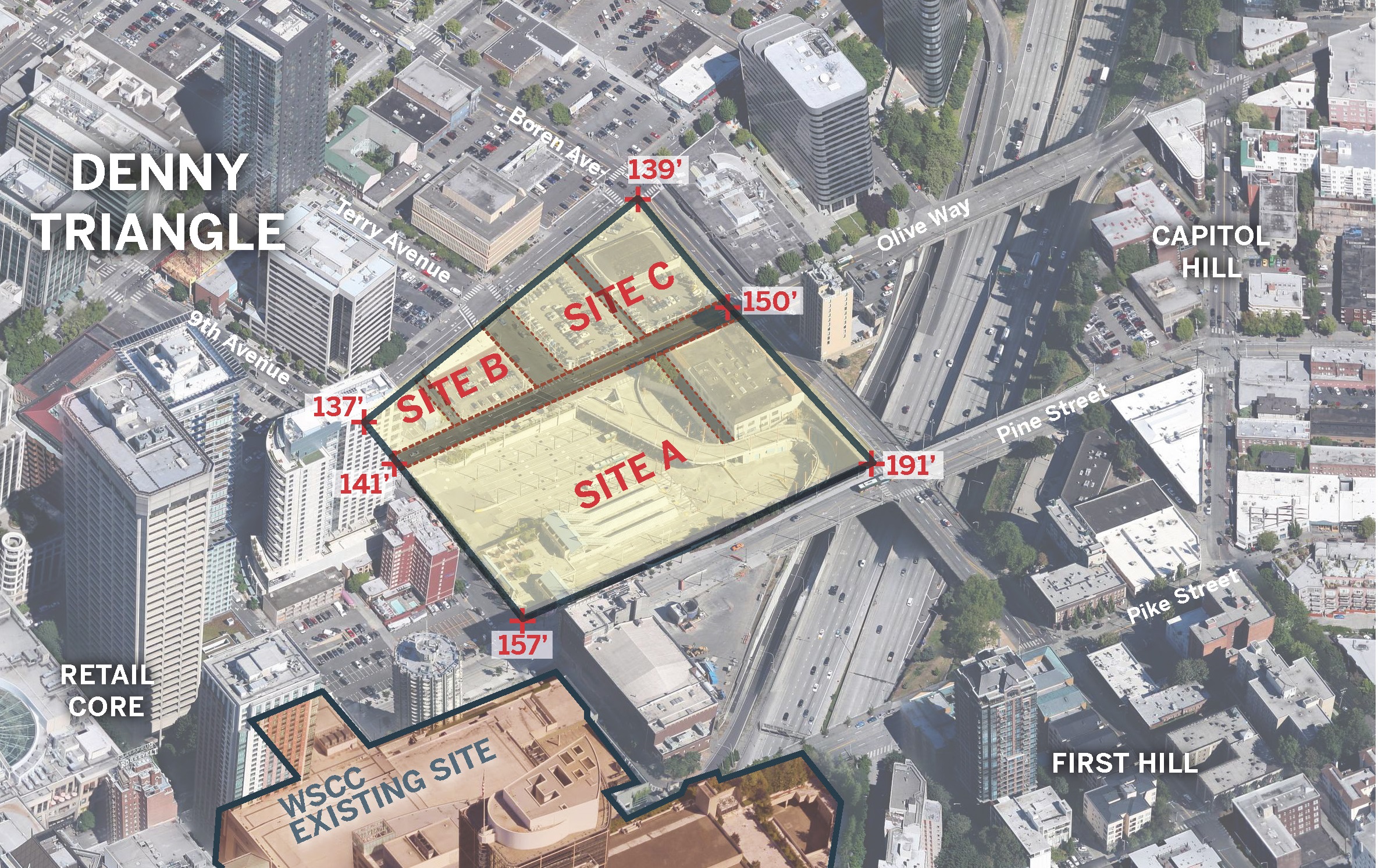

The tax increase is not driven by short-term rentals evading lodging taxes, but by the tacked on approach to public benefit and expanding scope of the project. A project with this amount of public money behind it, and a blank slate of four downtown blocks unencumbered by intervening streets and alleys could have created a positive transformation of the physical form and utility of this space, as other street and alley vacation proposals have done. Instead, the WSCC is using that contiguous block area to build just shy of 800 parking stalls at or above grade, as well as a truck loading facility with a curb cut double the size of what is typically allowed in downtown Seattle; all of this with the larger purpose of contributing to the nationwide convention center arms race that builds as much exhibition and ballroom space as possible with no consideration for what the surrounding community actually needs. The cash payment approach to public benefits increases the project cost, without improving the project for those who have to navigate around it.

Beverly Barnett, manager of right-of-way vacations for the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT), commented at a Seattle Design Commission meeting last spring that “A lot of the public benefit is being pushed to the perimeter or offsite. Our goal, looking at street vacations and a street vacation public benefit, is to make sure there are on-site amenities that make the experience for the general public moving through and around the site really important.”

Even with the large cash payments, the project barely gained approval from the Seattle Design Commission, the agency that reviews street and alley vacations before passing recommendations to City Council. In a 4-3 vote, dissenting commissioners noted the lack of even trying to create benefits on-site. Commissioner Rachel Gleeson stated, ”My main disagreement has to do with whether the site itself was ever considered for the onsite public benefit elements that we would expect to see on a project this size.” Commission chair Ross Tilghman added, “This is a project of exceptional size, location, and vacation requests and it has asked for exceptions at every point in the review process. When we have granted exceptions on past projects we have had good reasons to do so, but here the hand is simply forced.”

Additionally, rather than using this project to help solve downtown problems, the WSCC’s construction schedule is creating new ones. The WSCC’s current plan for early closure of Convention Place Station and bus access to the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel as early as spring 2019 has led transportation planners from across the region to scramble to try to find a way to keep commuters moving through downtown Seattle. The One Center City plan has been under development to help mitigate the “period of maximum constraint,” brought about in large part because of the WSCC’s disruptions. Unfortunately, One Center City planning has stalled leaving all modes of downtown surface transportation (pedestrians, bikes, buses, cars) bracing for years of increased crowding on already overcrowded streets, but the WSCC moves forward on the claim of future economic benefit.

The WSCC has argued that the expansion itself is a public benefit that will stimulate economic activity through out of town visitors coming to events. However, their own reporting of economic impacts leaves some gaping discrepancies. The 2016 WSCC annual report noted 311,136 room nights generated by events at the WSCC, but also lists direct visitor spending on lodging at $149.1 million. This equates to an estimated average of $479 per hotel room night, even though Kidder Matthews Real Estate estimated the average of downtown Seattle hotel prices in 2016 to be $218 per night, and the General Services Administration sets seasonally adjusted per diem reimbursement maximums between $157 and $202 per night. Any claims of economic benefit should be closely examined, as exaggerations run rampant throughout the WSCC’s marketing materials as well as the national convention industry.

Further, the WSCC consistently claims that it has turned away as much business as it has booked over the past five years, but KUOW pointed out the large amount of exaggeration that goes into that claim. The WSCC has also stated that it needs a separate facility to offset event set up and takedown between events, however, the current WSCC already has this ability through two separate, but connected exhibition halls, loading facilities and entrances made possible through previous aerial street vacations. These vacations left Capitol Hill residents with a view of a loading ramp over Pike Street as their gateway to downtown. As for the economic return on granting those vacations, according to WSCC annual reports, in 1997 (prior to doubling in size and adding a separate exhibition and loading facility), the WSCC hosted 40 national/international events that attracted 204,373 attendees, and 305 local/regional events that attracted 275,400 attendees. In 2016, the facility hosted 50 national/international events, but they only attracted 167,845 attendees, and the 285 local/regional events attracted just 230,011 attendees. The facility is far from full, and there’s no evidence more, very expensive space will lead to an equivalent amount of increased economic activity.

The WSCC’s claims of economic benefit do not hold up to scrutiny, and the construction planned for this site will cause more regional problems than it will solve. Councilmember Mike O’Brien has been admirably pushing for the WSCC to contribute more as part of its public benefit requirement, but the WSCC has shown that more financial contribution will only lead to a higher tax burden somewhere else, turning public benefit into public burden. The Community Package identified several widely supported public priorities, but none of them are actually a physical part of the convention center. Since those priorities are already being funded by increased taxes, taking out the middleman could save billions. The lodging tax should not serve as a constant source for construction of unneeded convention facilities while very obvious and urgent needs throughout the city go unmet.

The City of Seattle holds public rights-of-way as a function of the public trust. Any sale of a right-of-way is required to be in the public’s interest. Despite its name and access to public money, the WSCC sees no direct oversight from elected officials at any level of government. This is Seattle City Council’s only opportunity to provide needed oversight of a project that is financed by local tax revenue, before that tax revenue stream is tied to a massive debt for decades. The WSCC has shown no commitment to public benefit other than the minimum to get it through the public review process. In the interest of maintaining the public’s trust, City Council should reject this proposal and hold the WSCC accountable.