In December 2017 I had the fortune to pen, in my capacity as a columnist for City Arts Magazine, a retrospective essay about the impact of the Forward Thrust ballot initiatives. I looked backwards to Forward Thrust because I thought history could provide political answers that the self-proclaimed “progressive” present could not.

It seems to me that the rising popularity of the term “progressive” in our civic discourse has coincided precisely with some very unprogressive political phenomena in Seattle: rampant unaffordability in housing and an attendant homelessness crisis; enduring racial disparities in our school system; the proliferation of regressive taxes that contribute to displacement and economic insecurity; the tragic spectacles of police-authored violence in the form of brutal sweeps of the homeless and the murders of unarmed citizens of color.

As the calendar turned to 2018 and the 50 year anniversary of the Forward Thrust bond initiatives of 1968 was upon us, I wanted to take a deeper look at Forward Thrust than that initial 800-word editorial; and I wanted to take readers on a tour of its significance to the present day. So over the next few months, I’ll be distilling the results of this search here in The Urbanist, and in person at four neighborhood charrettes across the city with the help of Town Hall Seattle.

I’m fascinated by Forward Thrust because it seems a positive example of what civic boosters and journalists termed “The Seattle Spirit” in the late 19th century–a mélange of determination and folly that leads local residents to mobilize around large questions about the fate of the region and its people.

Sometimes that spirit has enabled self-sabotage and racial subordination. We cannot talk about Seattle without talking about the expropriation of human capital and resources from the indigenous peoples of the Puget Sound region, who hosted the city’s white settlers when they were in desperate need of direction, and were ceremoniously rewarded in the generation subsequent to the initial 1851 settlement with a slew of broken treaties and greedy land grabs. We cannot talk about urbanism without talking about enforced residential segregation that consigned African Americans and Asian Americans to decreasingly small portions of the city grid in the 20th century, then nearly booted them out of city limits altogether with the forces of gentrification in the 21st. And ultimately—as I’ll show in the course of this essay series–we cannot talk about Forward Thrust without talking about it as a political failure: a brainchild of downtown businessmen and political moderates who could not get the votes for their mass transit and public housing agenda because they refused to look for them in areas where the populations most impacted by these measures–people of color and low-income whites–usually live.

At the same time, “The Seattle Spirit” has revealed Seattle at its best. It was evidenced when workers across all unionized trades ground capitalist production to a halt in exchange for better wages and worker protections in the General Strike of 1919. It was apparent when civic engineers embarked on a series of dramatic regrade projects from the late 1890s until the Great Depression in the early 1930s, leveling the city’s steepest hills and readying now-stalwart neighborhoods like Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill for habitation. It was shown when the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party, founded the same year as the first Forward Thrust initiatives in 1968, provided free healthcare and school lunch to the city’s most vulnerable residents. And “The Seattle Spirit” was in action as area residents—in a rare move for a citizenry that was by most accounts defined by sleepy liberalism in the post-WWII period–took the future seriously enough to plan for it by approving (most of) the Forward Thrust initiatives.

When we talk about Forward Thrust, we are not parsing over the past so much as we’re forecasting our own future. Concern for our collective fate as a city was my impetus for starting this project. It will also be my motivation for sharing it.

##

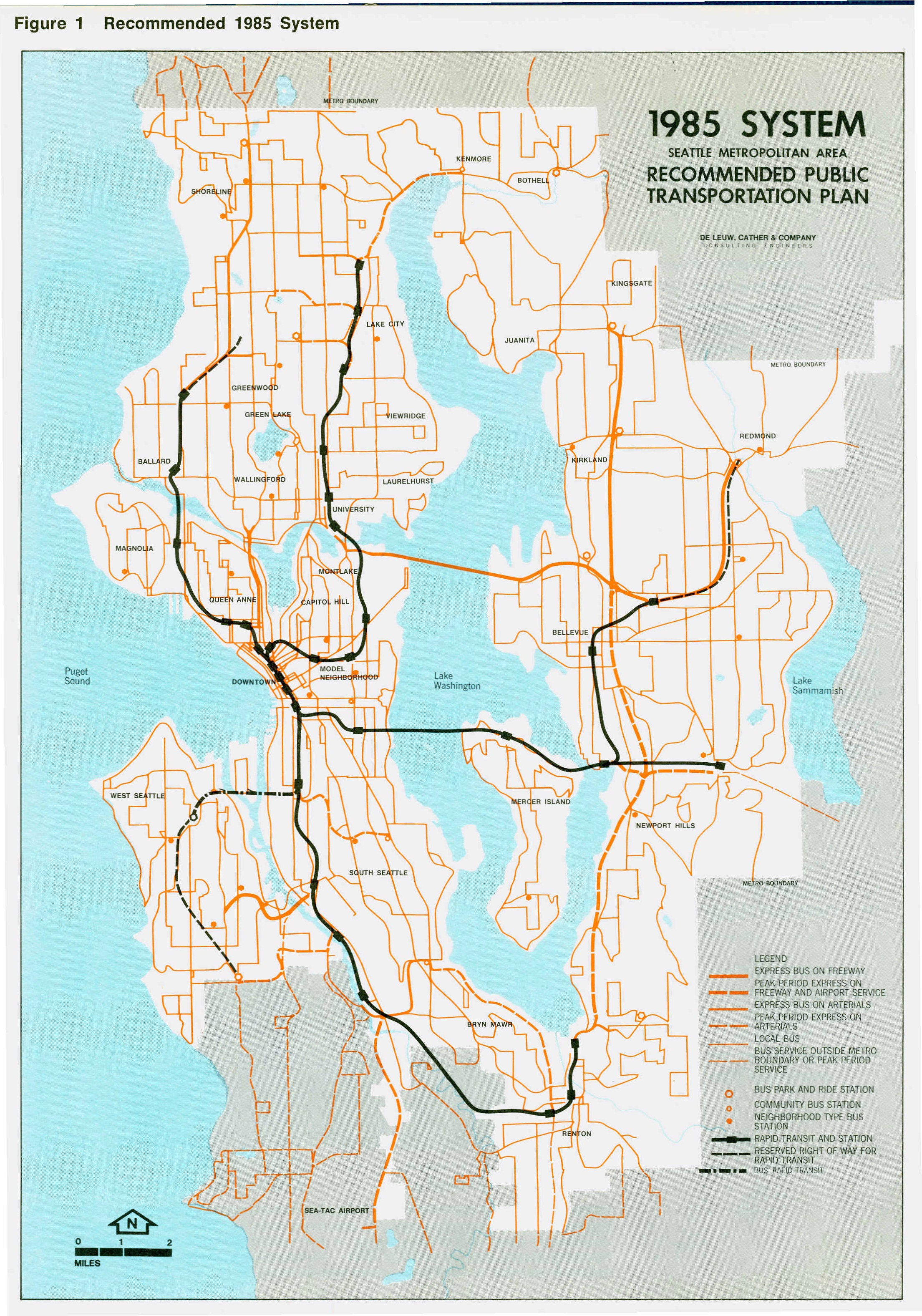

Forward Thrust was a gamut of ballot measures put before King County voters in two separate elections in 1968 and again in 1970. Conceived of by civic visionary Jim Ellis (a graduate of Seattle’s John Muir Elementary School), Forward Thrust was authored in the long shadow of the founding of METRO in 1958—a municipal corporation responsible for sewer disposal and mass transit that eventually resulted in the launch of King County’s bus fleet in 1973. Forward Thrust was intended as a set of comprehensive futurist reforms that would ready Seattle for its second post-WWII tidal wave of population increase. With an expansive subway system as its centerpiece, the Forward Thrust campaigns put new fire halls, modernized environmental infrastructure, hundreds of public parks, and facilities for professional sports before voters.

Unfortunately for transit enthusiasts, the fact that Forward Thrust was a King County initiative (and not a Seattle-specific one) lumped transit enthusiasts in with voters who were more reticent. The Space Needle had announced Seattle’s stature as a proverbial “world class city” in 1962, and the Seattle World’s Fair of the same year put the city on the global cultural map. Washington Senators Warren Magnuson and Henry Jackson were securing boatloads of federal funds for futurist research projects at the University of Washington, and even commandeered the majority of the funds that would have gone towards the construction of a subway system in Seattle had the Forward Thrust initiative for it passed at the ballot box.

In Seattle proper, life was dynamic and changing. In county outposts like Issaquah and Sammamish, where clusters of farmland could still be found in the 1960s, not so much. The suburbanite suspicion of downtown business types and metropolitan modernization diluted the urbanite urge for public housing and rail transit.

According to Roger Sale’s seminal city history Seattle: Past to Present (1976), Jim Ellis placed peripheral measures like professional sports and community centers besides his rail transit package because he thought they would increase the chance that the rail transit initiative—buoyed by positive associations with other, more popular measures—would pass in 1968. Tragically, King County voters approved of the side dishes but had a distaste for the entrée: the bond measure that led to the creation of the Kingdome and the subsequent arrival of the Seahawks and Mariners passed by a 62-38 margin. Bonds for youth service centers (72-28), and public parks including the Seattle Aquarium (65-35), sewer improvement (63-37), and new fire halls (70-30) enjoyed equally resounding victories, as Ellis predicted. Sadly, rail transit was the least popular of the measures, earning only 50.2% (county elections required a 60% vote share for an initiative to pass). The less-commented on but equally significant public housing bond also failed (58-42).

Encouraged by rail transit’s close margin of defeat in the 1968 election, Jim Ellis upped the ante on another two years of campaigning for Forward Thrust, this time coupling it with a measure for more community centers and a new county jail in 1970.

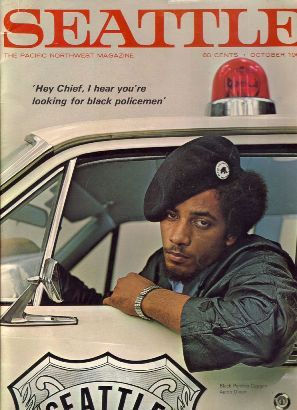

In the final installment of this essay series, I will tackle the question of whether Jim Ellis’ embrace of the carceral state help or hurt support for his transit initiative among urban voters. At the same time that Richard Nixon carried the 1968 presidential election with a “tough on crime” message that emphasized “law and order” to corral hippies and dissidents, many of those same activists were increasingly visible on Seattle’s social landscape. In October 1968, Black Panther Party chair Aaron Dixon appeared on the cover of Seattle Magazine, wearing a nonplussed stare while driving a police car to ironically highlight the Panthers’ opposition to the criminal justice system as an occupying force in Black urban areas of Seattle. Asian American activists in Seattle’s Chinatown/International District also vigorously opposed the proposed county jail. But Ellis would not have lumped it in with his mass transit initiative if he did not think it would have enhanced the subway’s chance for success.

Suffice it to say for now, history has revealed Ellis to be on the wrong side of a political equation that put voters of color and young people on one side of his calculus and Seattle moderates on the other. The subway initiative failed again in 1970, this time by an even greater than it did in the 1968 election (46-54). For good measure, the ballot measures which lumped the jail in with more police stations and community health centers were also rejected.

Started by the Black Panthers in 1968, the Carolyn Downs Family Medical Center remains open to this day. Ellis never got the chance to open his planned health center, and would have to wait until 1996 to see regional voters approve a rail system that began service in 2009.

“If rapid transit is to have a new beginning,” Jim Ellis told reporters after the 1970 failure, “it will have to come from people other than the Forward Thrust Committee.”

##

Who were these “people” Jim Ellis spoke of? When the Forward Thrust Committee incorporated as a nonprofit organization in 1966, it was composed of 23 men and one woman. Businessmen (eight) were the single largest constituency group on the committee, followed by elected officials (five), attorneys (three), civic association members (three), two utility company heads, a labor union leader, an architect, and a University of Washington professor. While this steering committee may have been reflective of the “official” types enfranchised by the Seattle political process, it was hardly representative of the emerging strains on the city’s civic fabric.

In a retrospective about the state of Seattle politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s, electoral wrangler Peter LeSourd writes that “by the close of the 1960s, the spirit of social and political activism that was spreading across the country had reached Seattle. Citizens groups were protesting plans to tear down Pike Place Market and to construct new city freeways. Opponents of the Vietnam War and African Americans protesting segregated schools and employment discrimination staged large and vociferous public demonstrations.”

The lack of a more significant working-class (or any activist) presence proved to be a political misstep for a campaign aimed at a heavily unionized populace during a tumultuous time in the city’s politics. But Jim Ellis’ political frame of reference didn’t leave much room for the populations he’d need support from if his big idea–rapid rail transit–were to succeed. In the remaining three installments of this essay series, I will relate questions about the successes and failures of Forward Thrust to the city’s present political landscape. For urbanists in particular, this discussion ought to have profound implications:

Often stereotyped as a mostly-white and white-collar fixation, urbanism–inasmuch as it exists as a concrete body of ideas–speaks to an appreciation for city life as a vector of human creativity, enlightenment, and liberation. In this sense, an urbanism that does not account for the specific social and political divides that segment cities will fail at delivering on this mandate for robust urban life. Take it from Forward Thrust: no ideology can be a narrow isthmus, and no city an island.

The featured image is a transit station envisioned in a Forward Thrust report. The image is courtesy of UW Special Collections.

Shaun Scott

Shaun Scott is a Seattle writer. His book Heartbreak City is available wherever books are sold.