Most economists dismiss rent control as a “quick fix” but tenant advocates say immediate relief doesn’t sound so bad.

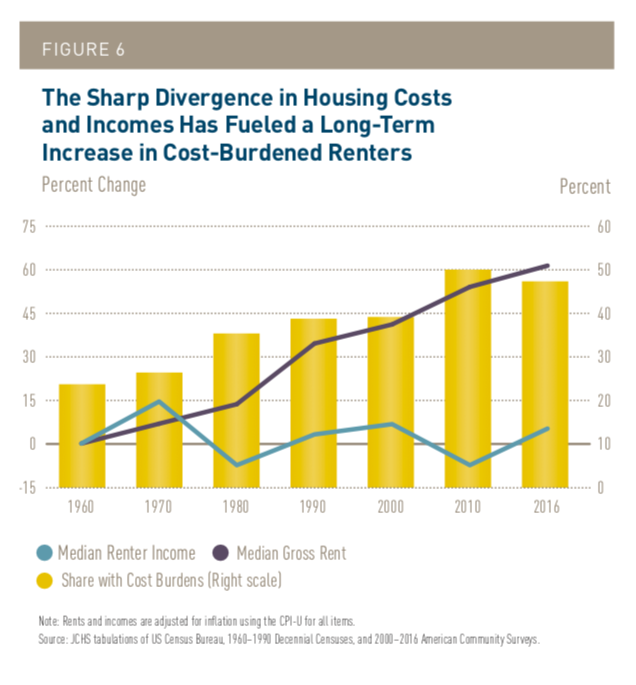

As the first US state to pass statewide rent control, Oregon has found itself at the vanguard of a new push for housing affordability. Similar to nationwide trends, housing affordability in Oregon has become a major issue in recent years as increases in housing costs have continued to outpace income growth, particularly for low-income Oregon households.

Governor Kate Brown has spoken highly of the bill, which she signed into law last week. In the Statesman Journal, Governor Brown said that SB 608 “is a critical tool for stabilizing the rental market throughout the state of Oregon. It will provide immediate relief to Oregonians struggling to keep up with rising rents and a tight rental market.” That relief is modest, with rent increases capped at 7% plus inflation per year in rentals 15 years or older.

While rent control is popular in some circles, economists are skeptical that it will bring about long-term affordability benefits.

“You cannot get economists to agree on nearly anything,” said James Young, Director of the Washington Center for Real Estate Research (WCRER) at the University of Washington, “but one thing they do tend to agree on is that rent control is a disaster. In the long run, [rent control] does the opposite of what it wants to do.”

Economists do seem to agree that the best way to resolve housing affordability issues is to create more housing. But with restrictive land use and zoning policies in place and booming economics in both Oregon and Washington, increasing housing capacity to levels sufficient to meet demand is difficult. Building new housing also takes time.

In contrast, rent control offers an immediate reprieve from skyrocketing costs and attempts at economic eviction (e.g., when landlords try to force tenants to move with huge rent hikes). As a result, rent control advocates believe it is a tool that should be used to help low-income renters.

“Rent control is the fastest and most effective policy for stopping the displacement of renters,” said tenants’ rights advocate Dinah Braccio to KOMO News. “The rising rents are leading directly to homelessness.”

SB 608’s sponsor, Shemia Fagan, who represents East Portland, spoke of her mother’s struggle with homelessness during her introduction of the bill.

“The stability of an ordinary life shouldn’t be that hard,” Fagan said. “The basics shouldn’t be that hard. But for many so Oregonians, basic stability is out of reach.”

A Housing Affordability Crisis

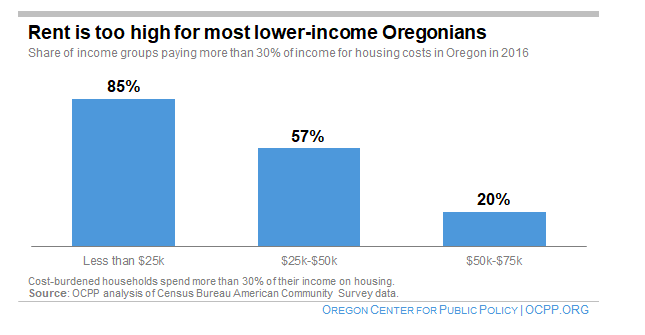

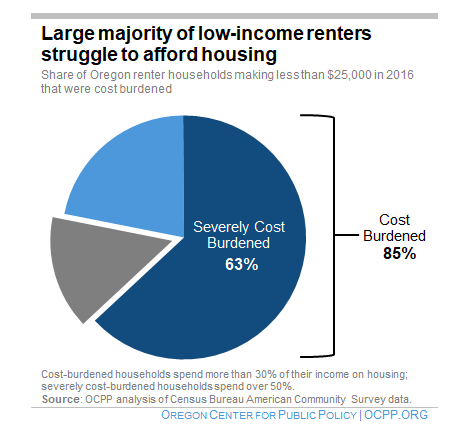

One-third of Oregon households identified as “cost burdened” or paying more than thirty-percent of their income toward housing. Among renters the situation is even more dire.

Over 51% of Oregon renters are cost burdened; more than half of those renters have been identified as “severely cost burdened” or paying more than 50% of their income toward rent. These figures place Oregon just above nationwide averages for cost burdened renters.

By placing an annual cap on rental cost increases and limitations on no-cause evictions, Oregon lawmakers are seeking to ease the cost burden on low income households and curb displacement.

Displacement and homelessness are major problems in Oregon, which ranks first in the nation for the number of homeless children and youth.

What to Know about Rent Control in Oregon

Dubbed by NPR’s Planet Money as “rent control lite,” Oregon’s recently passed legislation has been framed as a compromise between housing affordability advocates, landlords, and housing developers.

Under the new law, landlords can only increase rents once annually, and increases are capped at 7%, plus the consumer price increase (CPI), an official measure of inflation. Using this formula, in 2019 Oregon landlords are allowed to increase rents by up to 10.3%.

Supporters of the bill believe that this cap should be generous enough to not hurt the property investment market.

“I think where 7% came about was: let’s look at how rents have moved over the last couple years, what’s a reasonable rate of return if you’re a business owner,” said House Speaker Tina Kotek, D-Portland in a statement to the Statesmen Journal. “We felt like at 7% plus CPI you could address a lot of concerns and also provide predictability for the tenants.”

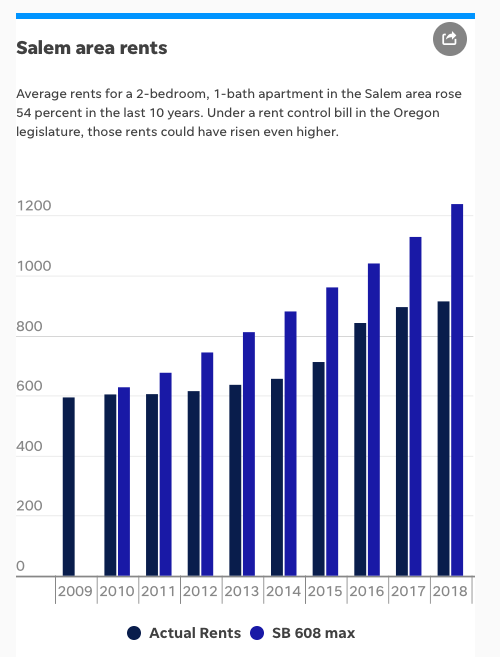

The Statesmen Journal also published an analysis that found that in the Salem metro area annual average rent increases have fallen short of the rent control cap.

If the rent control legislation had taken effect in 2009, rent in Salem would have been permitted to increase to thirty five percent more than current prices. The same is true of Portland, where rents could have grown thirty one percent higher.

Additionally, rent control caps only apply to properties built in the past fifteen years. Landlords have fifteen years from the day their unit’s first occupancy certificate is issued before they are subject to the cap. Critics have argued this design feature may encourage rent gouging in the lead up to the cap kicking in at the 15-year mark. The exemption for newer buildings was included in an effort to ensure the bill does not result in a decrease in new housing production. However, James Young of WCRER insists that it will still dampen housing production.

“Fifteen years is when maintenance costs become an issue for large capital developments,” Young said. “This means that major maintenance costs will kick in at the same time that rent caps kick in.” He added he believes that reduced profit expectations will result in fewer new developments.

In addition to capping rental costs, the bill also provides new protections for renters from no-cause evictions.

During the first year of tenancy, landlords are required to provide thirty days written notice for eviction. After the first year, the requirement increases to 90 days written notice for a “qualifying reason.” Examples of qualifying reasons include: plans to demolish the unit or convert it to nonresidential use, plans to repair or renovate properties that have been found unfit for occupation, and owner occupancy of the unit by either the landlord or an immediate family member.

The legislation largely does away with no-cause evictions, except during the first year of tenancy. In that first year, landlords have to give 30 days’ written notice for eviction.

Will Rent Control Prove a Boon for Renters?

Most economists seem to be in agreement that rent control has long-term negative effects on housing markets. Assar Lindbeck, a well-known Swedish economist, has even gone as far to say that “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.”

When asked if Oregon’s specific housing affordability crises and “rent control lite” model might prove to be an exception to economists’ concerns, Young was insistent that the net effect of rent control on housing prices would be negative. Most of the academic research on rent control is on stronger versions than Oregon’s 7% cap plus inflation version.

According to Young, whenever prices are capped, expectations on returns adjust in response, leading to two detrimental effects. Firstly, sales prices for properties decrease, reducing the incentive to build new housing developments. Secondly, tenants stop moving, resulting in a lack of movement in the market. In Oregon’s case, rents increasing up to 10% annually could still be a pretty push out the door for tenants.

“The [renters] who are already there win the lottery,” Young said. “But everyone else suffers.”

A study of stricter rent control policies in San Francisco by the Stanford Graduate School of Business, which concluded that “rent control creates both winners and losers—even among renters.” Longtime tenants in rent-controlled units were found to have benefited greatly, while newcomers ended up paying higher rents because of reductions in housing supply. A 2018 Brookings Report on the economic research found rent control counterproductive in the long run and suggested in San Francisco’s case loopholes encouraging condominium conversion can “fuel gentrification.” The report advocates for subsidies as an alternative.

To help increase housing supply in Oregon, Governor Brown has also proposed a $400 million assistance package as part of her state budget. The majority of the funding would be spend on building affordable units across the state; however, some funding would also be spent on rental assistance and homelessness prevention.

Meanwhile, it appears that an increase in housing supply led to average rents leveling off in Portland in 2018. Rents in Portland increased by about two percent in 2018, which was the lowest increase amount since 2011.

Could Rent Control Come to Washington State?

The short answer, for now, is no. In 2018, the Washington lawmakers chose to uphold a statewide ban on rent control, which has been in effect since 1981. No lawmaker has proposed a rent control ban repeal during the 2019 legislative session; however, a number of bills aimed at increasing rights for renters have been proposed. Some examples include:

- HB 1440, which requires 60 days written notification of rental rate increases;

- HB 1453 and SB 5600, which extend the “pay or vacate” period; and

- HB 1656 and SB 5733, which require “just cause” evictions.

In terms of increasing housing affordability, Young advocates for zoning for increased density and loosening liability restrictions on condominium construction. SB 5334, which has been passed by the Senate and is currently under committee review by the House, would reform condo liability laws in Washington, paving the way for increased condo production.

Young argued both Washington and Oregon’s housing markets currently suffer from the fact that condo liability laws push people into rentals who would otherwise be homeowners, resulting in developers remaining in the rental market, which improves the quality of rental properties, but also drives up rental prices.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.