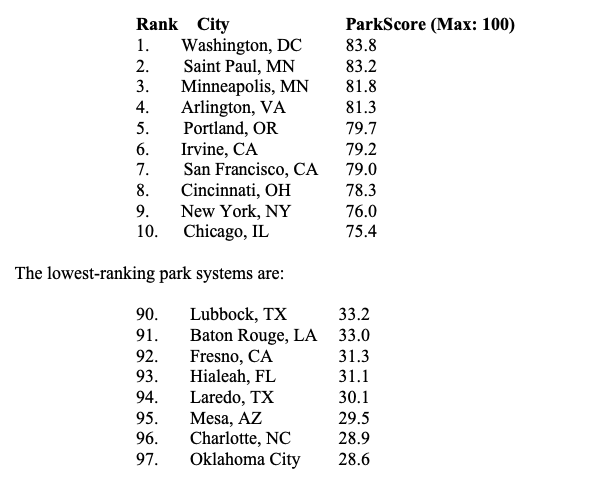

Seattle continued its strong performance on the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore Index in 2019, holding on to 11th place in the national rankings just behind Chicago. Washington, DC ranked first followed by Saint Paul and Minneapolis.

The Trust for Public Land (TPL) is nonprofit that has protected more than 3.3 million acres of open land and completed more than 5,400 park and conservation projects since 1972. One of the organization’s primary goals is to ensure that all Americans live within a 10-minute walk of a park. According to 2019 data, about 72% of Americans meet that criteria.

Although 72% might seem like a fairly strong figure, access to parks is not equally shared. Despite the fact that there are 23,727 parks in the 100 largest U.S. cities, about 11.2 million residents of those cities do not have a park within a 10-minute walk of home.

“As few as 8,300 new parks in places where they are needed most would close the gap in park access in our 100 largest cities. At current rates of investment in park creation, it will take more than 50 years to build enough new parks to fill this gap,” said Breece Robertson, Chief Research and Innovation Officer at TPL. “But because we now know exactly where to site the parks, we know the first 1,500 could solve the problem for nearly 5 million people.”

The top ten best and worst cities’ rankings broke down as follows:

What metrics does the ParkScore Index measure?

ParkScore rankings are based equally on four factors.

- Park access, which measures the percentage of residents living within a10-minute walk of a park;

- Park acreage, which is based on a city’s median park size and the percentage of city area dedicated to parks;

- Park investment, which measures park spending per resident; and

- Park amenities, which counts the availability of six popular park features: basketball hoops, off-leash dog parks, playgrounds, splashpads and other water play structures, recreation and senior centers, and restrooms.

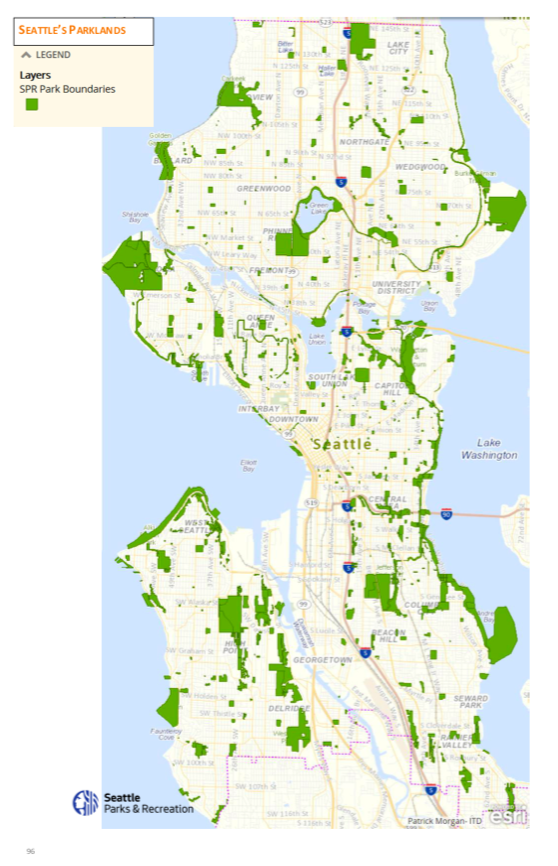

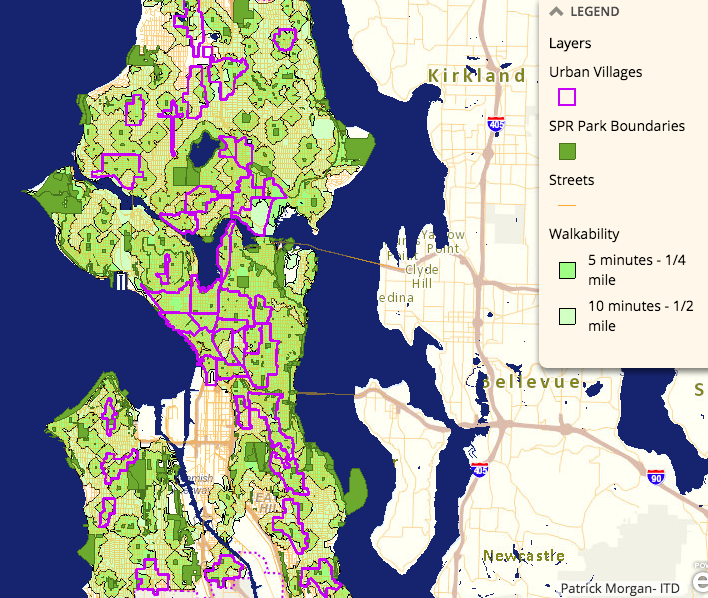

Seattle scored particularly well for park access. According to TPL, 96% of Seattle residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park, among the highest scores in the nation.

Proximity on a map does not always equate to access. Instead of measuring distance to a local park, ParkScore considers the location of park entrances and physical obstacles to access. For example, if residents are separated from a nearby park by a major highway, the ParkScore Index does not count the park as accessible to those residents, unless there is a bridge, underpass, or easy access point across the highway.

Moreover, while access to small parks is widespead, a Seattle Parks and Recreation open space gap analysis has suggested that larger parks and green spaces are not equitably distributed, with accessibility tending to be worse in lower-income areas. Marquee parks, meanwhile, tend to be ringed by restrictive single family zoning.

Walkability from open spaces based on a 2016 analysis. (City of Seattle)

Investment was another strong area for Seattle. Seattle spent $279 per person on its park system in 2019, trailing only Minneapolis’ $299 and San Francisco’s $318–all far above the national average of $90 per person.

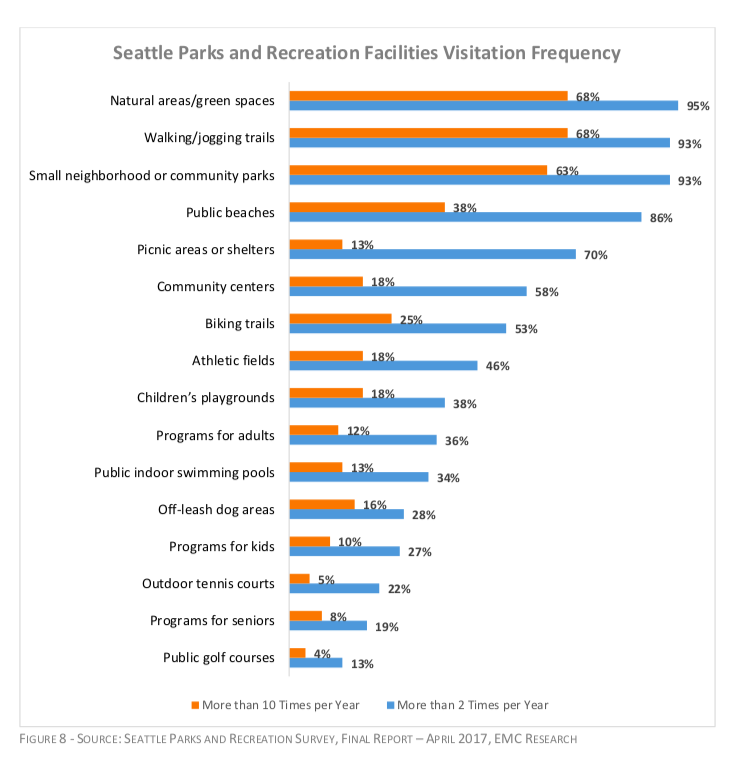

In terms of amenities, Seattle stood out for its commitment to dog parks, with about two off leash facilities for every 100 residents, a number that is almost double the national average.

But Seattle’s overall score was hurt by its small median park size of 2.4 acres, which is below the national ParkScore median of 5.0 acres.

At the same time, when the City of Seattle’s 2017 Parks and Open Space Plan identified what park facilities Seattleites visit most frequently, small neighborhood or community parks came in number three on the list, indicating that these small parks are being used by residents.

Seattle Parks is seeking feedback on concepts for a new park in West Seattle

A landbanked site at 48th and Charlestown in West Seattle will become one of Seattle’s newest neighborhood parks. The .33 acre site was acquired with the help of King County funding, which restricts its use to low-impact, passive recreation and requires that the majority of the land is green open space that can provide stormwater infiltration.

Currently, the three concepts include:

Dog Friendly – this concept would include a fenced off-leash area for dogs, a lawn, a loop trail, and a picnic area with tables.

Community Green – this concept would include a big central lawn, a loop trail, a nature discovery trail, a dog comfort station, and a small plaza-like area with moveable tables and chairs.

Neighborhood Play – this concept would include a play area, a lawn, a nature trail, and a small plaza-like area with moveable tables and chairs.

Seattle Parks is currently seeking community feedback on its park concepts for 48th and Charlestown site. The survey is open until May 24th.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.