Seattle is looking to significantly cut the environmental impact of its new commercial and residential buildings with the adoption of the 2018 Seattle Energy Code, which is being kicked around the Seattle City Council in new legislation. This legislation would realize a code consisting of the 2018 International Energy Conservation Code with Washington state amendments and Seattle amendments. It will improve the building insulation, space heating, lighting, and renewable energy systems standards for new construction of multifamily buildings taller than three stories and all non-residential buildings.

The City’s amendments go farther than state amendments to the 2018 International Energy Conservation Code, expanding coverage of regulations, and levying more restrictions and greater energy efficiency requirements. Among the changes are:

- Revision to the code’s intent to include reduction of carbon emissions, on top of energy efficiency;

- Recognition of heat loss from through-wall mechanical equipment, concrete balconies, and window frames when calculating the insulating value of walls;

- Requirements for improved thermal properties of fenestration–design of windows and doors in a building–by 10-15% less heat loss; luminaire-level lighting controls or networked light control system for open office areas larger than 5,000 square feet; electrical receptacles and circuits at dwelling unit gas-fired appliances, to accommodate future electric appliances;

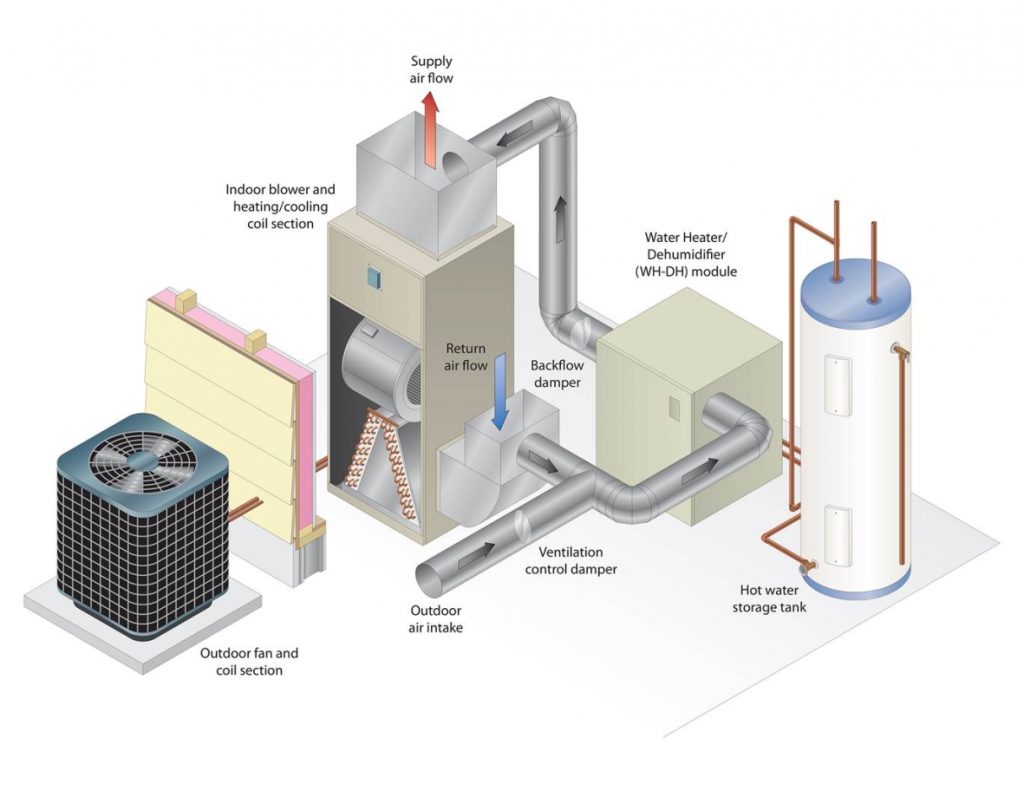

- Addition of multifamily and medical office buildings to the list of buildings required to comply with the HVAC Total System Performance Ratio in the code; new control and efficiency provisions for ventilation and heat recovery at 60% energy recovery effectiveness compared to 50% required by the state code; and insulation, control, and efficiency improvements to hot water circulation;

- Formalization of existing code that restricts heating systems to exclude fossil fuel and electric resistance in commercial buildings, and an extension to include multifamily buildings more than three stories tall for that exclusion;

- Exclusion of fossil fuel and electric resistance central water heating systems for R-1 and R-2 occupancy buildings;

- Reduction of interior light power allowances to 10% below state energy code levels;

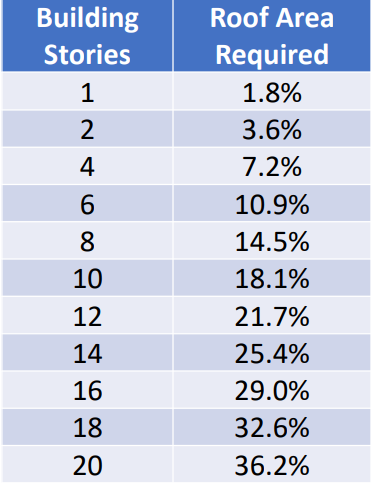

- Increased on-site renewable energy requirement for all new buildings and additions 5,000 square foot or greater from 0.07 Watt per square foot (W/sf) to 0.25 W/sf based on area of all floors–exemptions for affordable housing projects and transfers; efficiency package credits from six to eight, as listed in section C406;

- Setting target performance path targets 12% above Washington state Building Performance Factor values; and

- Prohibition of envelope heat loss more than 10% worse than allowed in the prescriptive code, half of the state ban.

On Wednesday, the city council’s Land Use and Neighborhoods Committee and City staff discussed the proposed changes. During the meeting, Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda introduced an amendment to expedite implementation of the space heating from the original January 1, 2022 date–recommended by the construction advisory board after stakeholder feedback–to June 1, 2021. Councilmember Debora Juarez sough clarity on why move up the implementation date now, City staff mentioned that it was unusual for delay, there’s no technical need for that delay, and that the technology is here.

On the other hand, staff and Land Use Chair Strauss noted that the heat pump water heater technology wasn’t widely used and available, prompting the slower implementation. Thus, that part of the bill would keep to the original Jan 1, 2022 implementation proposed by Mayor Jenny Durkan and Seattle’s Construction Code Advisory Board. That would also allow for more stakeholder feedback and state legislature session considerations.

The amendment passed with a 3-2 vote in favor of the motion, Councilmembers Juarez and Alex Pedersen were the two no votes. Councilmember Andrew Lewis had his own amendment, but noted that he’ll raise it as its own legislation in the future for broader applicability. The amended bill passed 4-0 with Councilmember Pedersen abstaining, moving it forward to the next city council meeting.

Examining the major changes

On top of all the energy efficiency standard improvements, air source heat pumps are elevated as the favored heating system. At The Urbanist, I’ve previously discussed heat pumps as an energy efficiency option for buildings. In that article, I covered geothermal energy and ground source heat pumps.

[these] heat pumps are used to access the steady temperatures of the subsurface. These ground-source heat pumps work by applying electricity to transfer heat from one reservoir to another reservoir.

For heating, fluid–often water or a water-based refrigerant–is drawn from an open or closed looping of pipes that access the thermal energy stored in the subsurface. Fluid heated by steady subsurface temperatures is then compressed in the heat pump, heating it up; that heated fluid is then used to heat a residence, cooling the fluid. The cooled fluid is next decompressed/cooled further and sent back underground where the subsurface temperature can heat up the fluid again and repeat the process. For cooling, the process is reversed and is just like how a refrigerator works.

Air source heat pumps operate in a similar fashion, but instead of using the temperature of the subsurface they use the temperature of the air. Air source heat pumps are not as efficient as their ground source counterparts because their system often has to do more work to bring air temperature refrigerants up to desired temperatures. That being said, air source heat pumps are much cheaper to install because they don’t require excavation or drilling. This technology is much more efficient than fossil fuel and electric resistance heating and central water heating systems. For example, the United States Department of Energy writes that a heat pump equipped with a desuperheater–that recovers waste heat– can heat water two to three times more efficiently than an ordinary electric water heater. Of course, these heat pump systems come as an extra cost compared to common systems, but the superior efficiency should lead to a lower lifetime cost of ownership.

Ground source heat pumps are one of many exceptions to installing an air source heat pump. For water heating systems, developers may also use solar thermal, wastewater heat recovery, other approved waste heat recovery, water-source heat pumps, and combinations thereof. Other systems meeting the requirements of the Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance Advanced Water Heater Specifications are also allowed. Due to its wider application exceptions for heating systems are more extensive. Uses like defrosting, temporary systems, emergency generation, district energy, kitchen exhaust, pasteurization, small systems that provide less than 5% of heating capacity, those that have low interior heating requirements or require fossil fuel or electric resistance space heating, and dwelling and sleeping units may ignore some or all of the requirements.

Next, the code update would require more than tripling peak photovoltaic energy production per square feet from 0.07 to 0.25 W/sf of conditioned space, mandating an increase of Seattle’s distributed renewable generation. This’ll likely come in the form of solar panels, as other renewables like geothermal and wind are not strong or existing options for Seattle’s built environment.

Next steps for the bill and energy efficiency

This code update is just another step that we need to take to deal with the climate crisis. Fossil gas from Puget Sound Energy produced just short of 860,000 metric tons of CO2 emissions in our commercial and residential buildings or just under 15% the city’s CO2 emissions in 2018. The update will only tackle a small segment of new residential buildings and most new commercial buildings. The City will have to make bold changes to electrify the vast fossil fuel heating capacity of existing buildings, including all the single-family homes that use natural gas heating.

The legislation will go before the whole city council next week. Let your councilmembers know that you support this step toward decarbonizing our local energy usage. And perhaps offer the helpful suggestion to ratchet up efficiency requirements for single family homes, since they much more energy intensive per capita than multifamily buildings.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.