From a bird’s eye view, Seattle’s South Park neighborhood is cut in half by SR-99, divided diagonally from one end to another. The highway, which brings in noise and vehicle pollution, is just one of many issues that burdens the isolated neighborhood. But South Park residents, known for their solidarity, want the highway gone, and that could soon be a reality with momentum growing behind its possible removal.

Cultivate South Park, a community nonprofit headed by Coté Soerens, a local business owner and activist, is joining a national movement that is seeing communities across the country decommission highways and freeways. A report by Congress for New Urbanism, a nonprofit that promotes “people-centered” and walkable urban design, shows potential projects across the country in different stages of dismantling obtrusive highways. The report, Freeways Without Futures, presents this moment as pivotal to freeway removals with the emergence of the Reconnecting Communities Act that was introduced in Congress in April giving these projects much needed steam.

The Reconnect South Park project not only wants to remove the segment of SR-99 that cuts through the neighborhood, it also wants to create a land trust to ensure the 40 acres it will free up are developed equitably. The land trust would allow residents a say in how the public land should be used.

“Our neighborhood needed more land for community and we’re making more land by decommissioning a monument to redlining,” Soerens says while she drives under the SR-99 overpass on South Cloverdale Street.

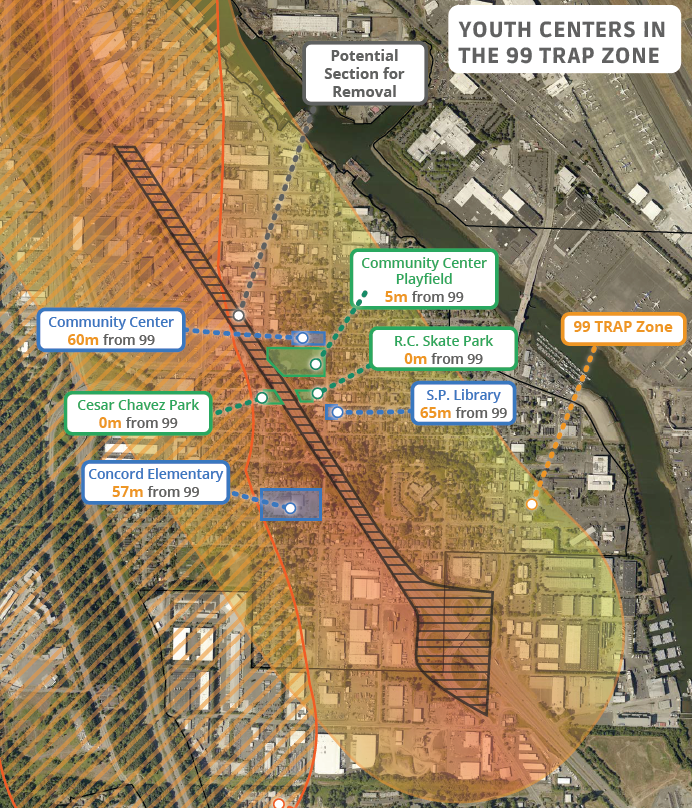

Soerens gestures to her left. “So, imagine if you remove that and you can reconnect Cesar Chavez Park with the skatepark and the community center,” she says, wide-eyed and smiling, while her baby coos in the backseat.

Soerens is a powerhouse within South Park. With the help from her surrounding community members, she led initiatives like “El Mercadito,” a food bank project that fed her community during the height of the pandemic. South Park is known for lacking any major grocery store, earning it the label of a food desert neighborhood. But Soerens doesn’t like being the hero of the story, after all, she says like “El Mercadito,” this project is a resident-led dream.

Of all the neighborhoods in Seattle, South Park is not only among the most diverse, but also the youngest, with little over 31% of residents under the age of 18.

It’s one of the reasons Soerens and her co-organizers want to badly decommission the segment of SR-99 that cuts through the neighborhood. The highway is steps away from many places where children congregate.

A map illustrates how the community center, the skate park, the library, Cesar Chavez Park, and Concord Elementary School are all within 65 meters from the highway. The health risks facing South Park residents have long been known — nestled between major highways, industry, and the Duwamish – a superfund site and one of the most polluted areas of the country — life expectancy for residents is much less than those of their neighbors.

“My kids have a 10 year less life expectancy than their friends up in North Seattle,” Soerens posits, her baby now crying in the backseat.

Residents have a life expectancy of about 73 years.

Crystal Brown has lived in South Park for the past six years. She used to be a teacher and says when she found out about the discrepancy in life expectancy for South Park residents, she felt a call to action.

“I don’t think that’s fair,” Brown says. “If we can stop it now, and I know this is cliché, but make it a better future for the kids in South Park, that’s my driving motivation.”

As part of Cultivate South Park’s next steps toward making this dream a reality, Brown is currently interviewing South Park residents for a video. The video will be used as part of the project’s fundraising initiative and to engage with the community. Brown is asking residents to imagine their life without the SR-99 corridor in their backyards, what would they want to see instead?

“I think the freeway is something residents have just accepted,” Brown says. “Who thinks you can move a freeway?”

Many, such as the Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, have pointed to the disproportionate impact freeway projects have had on Black and brown communities over the years, often completely displacing their communities. The conversation is gaining traction too because of a recently passed $1 billion infrastructure bill. Buttigieg’s remarks are echoed by other politicians, as well, some closer to home.

Ahead of the legislative session next year, the city of Seattle has already included highway removal within its agenda.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold, who has rallied behind Cultivate South Park’s mission said she looks forward to giving testimony in Olympia in support of this project. She also said South Park is a prime example of a place that is layered with environmental impacts that residents have had to contend with for generations.

“I don’t think there’s another neighborhood like that with these sorts of challenges,” Herbold says.

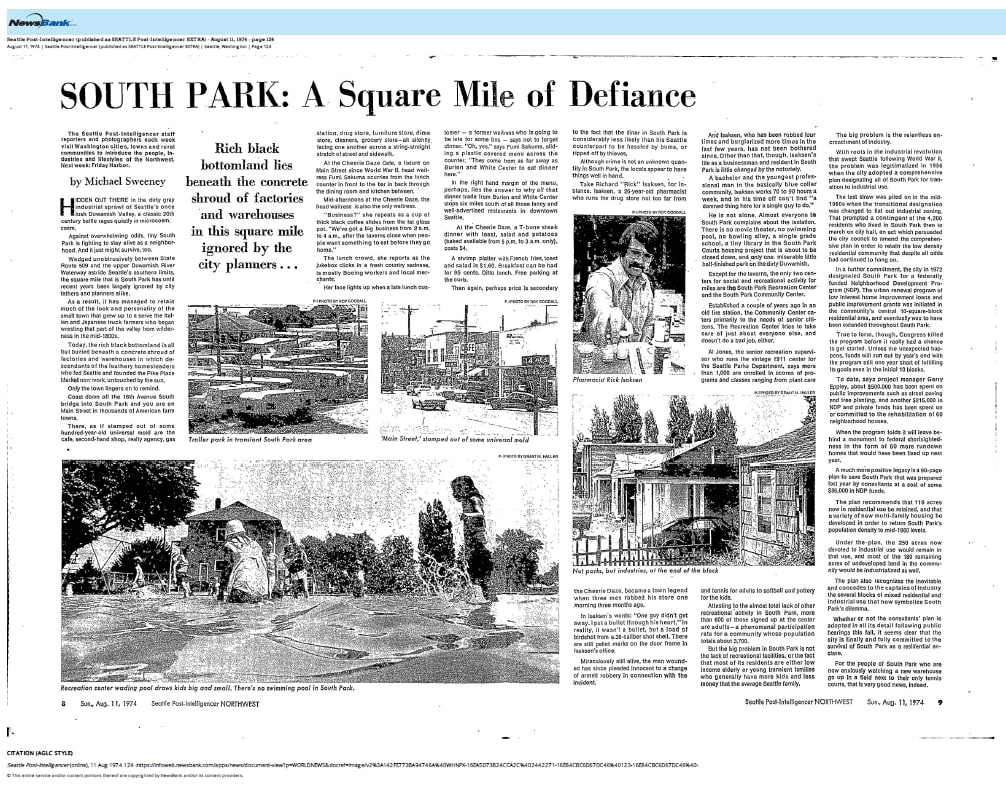

This past year, Seyyada Burney interned at the city’s Office of Planning & Community Development. She decided to piece together the history of South Park and the highway that cuts through it. What she found was both inspiring and alarming.

For generations, South Park has faced displacement after displacement in more ways than one, be it colonization, racism, or rezoning efforts. First, when the Duwamish people were pushed out by settlers. Again, when Japanese farmers in South Park were interned during World War II and then when Seattle rezoned the area for industry to great opposition from residents in the mid-1960s.

“I was really stunned by how much has happened within this one square mile neighborhood,” says Burney. “It’s a testament to how resilient this community is.”

During her research, Burney also discovered that the highway that bisects South Park, which was built in 1959, was demoted from being a federal highway to a state road sometime between 1963 and 1969.

It’s a detail that isn’t lost on Soerens.

To get this project off the ground Soerens has tapped the shoulders of many stakeholders, ranging from those representing her industry neighbors, politicians, and organizations doing similar things across the country.

Earlier this year, Soerens connected with Placemakers.US, an online resource group and movement that connects people trying to create community-driven spaces. That’s how she met Madeleine Spencer and Ryan Smolar from California. When she told them about her project they immediately decided to jump in and help her as they’d been working on a United Streets of America project. That project was invigorated by the way the pandemic had changed the way cities across the country use streets.

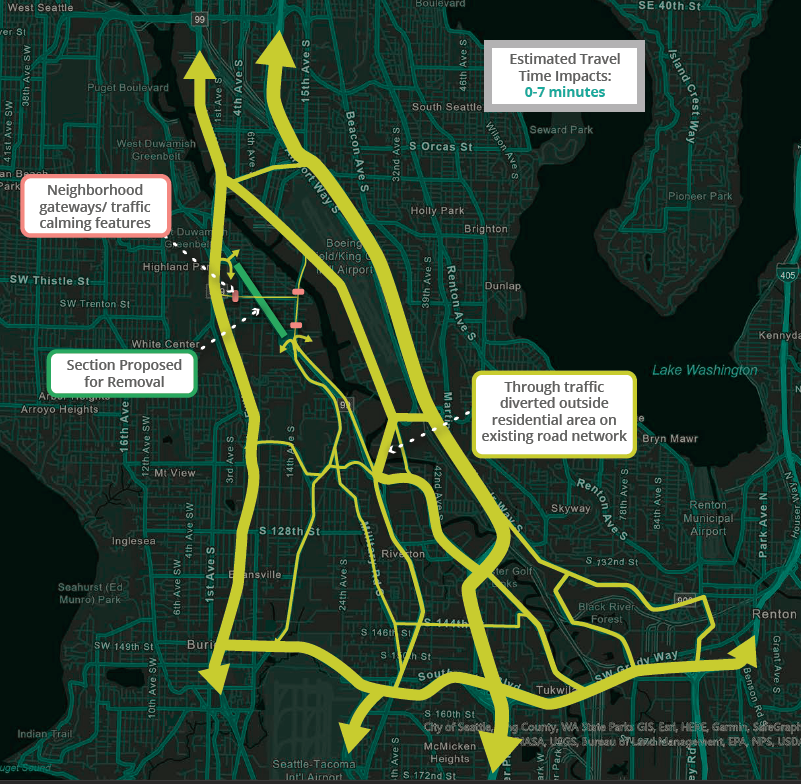

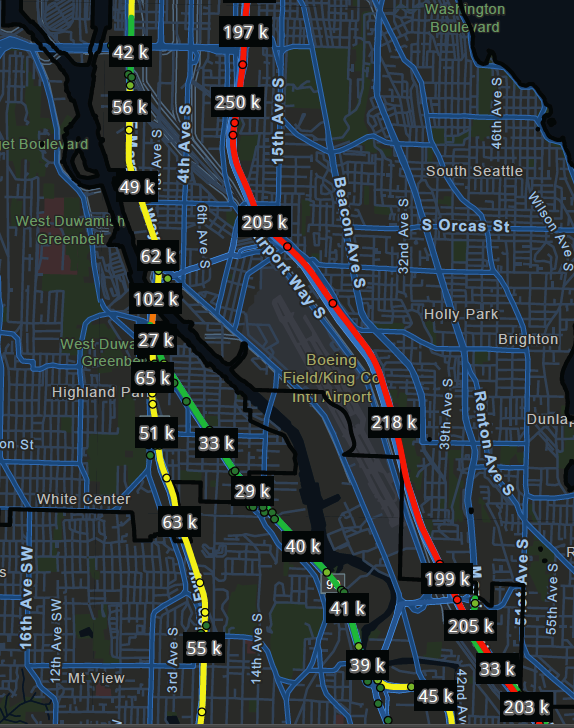

Not only does Soerens think the highway was a mistake, but numbers provided with help from Smolar and Spencer found that SR-99 is barely used compared to 509 to the west and I-5 to the east. Combine that with its 1969 demotion to a state road “it’s the smoking gun,” says Soerens.

Still, the project faces challenges, which politicians such as Sen. Rebecca Saldaña point out.

Saldaña, who sits on the transportation committee as vice-chair, says transportation and infrastructure projects always come with huge price tags but adds that this project is just the kind of thing that could fit under new federal funding.

“The community in South Park are fierce organizers and bring a lot of heart to what they do, and I think there is a pathway and it’s building up the organizing to change the conditions to make this dream possible,” says Saldaña.