This month, King County announced roughly 45,300 residents experienced homelessness at some point during 2019, while in 2020, the number dipped slightly to 40,800 people. The revised figures are from a new integrated reporting system that the County considers far more accurate than its predecessor.

The statistics paint a sobering picture of the magnitude of the region’s homelessness crisis. To put those numbers in context, the amount of people who experienced homelessness each year roughly equates to the population of Edmonds, which the 2020 census cited at 42,800 residents.

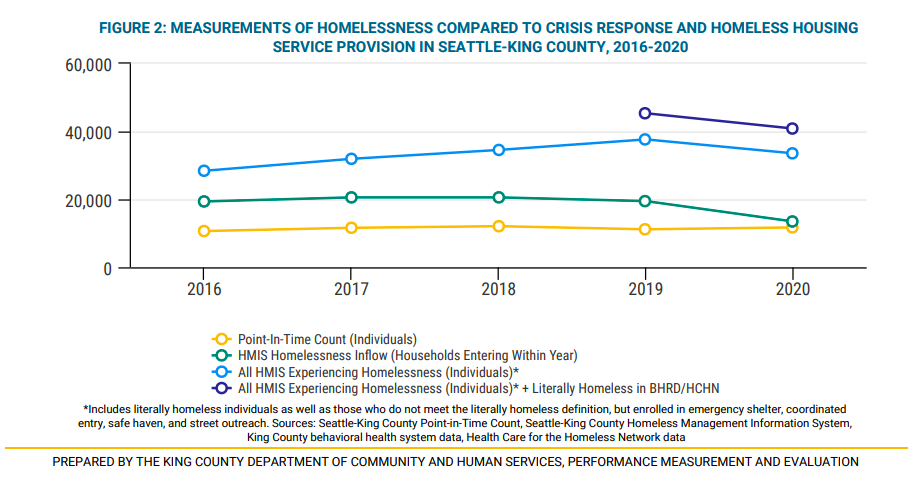

Prior to its new integrated data collection system, one of the methods King County used to estimate the number of people experiencing homelessness was its annual Point in Time Count. Since 2005, the federal government has required counties to conduct a PIT Count at least every two years in order to maintain eligibility for funding. But PIT Counts, which are conducted by volunteers and service providers relying on firsthand observation, fall short in several ways. By counting only once per year, they fail to capture the people who experienced homelessness at other points over the course of the year. The PIT count also struggles to locate homeless folks who have sought out remote locations so as not to be bothered or who are couch surfing. Thus, homeless experts consider PIT counts to be undercounts.

In January 2020, King County’s PIT Count estimated that 11,751 people were experiencing homelessness — an estimate that came up significantly short of even the 13,500 people who were newly entered in the County’s homeless response system that year. Looking at all Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) programs, the number spiked to 33,500 for 2020. Yet, evidence suggested those numbers were still coming up short — a hunch that the new report backs up.

Underestimating the number of people experiencing homelessness leads to many repercussions. Without having access to homeless counts that accurately reflect the true scale of crisis, cities and counties continue to request funding that falls far short of real needs for emergency shelter, social and medical services, and affordable housing. Many taxpayers become upset when they observe the homelessness crisis continue to worsen even as funding increases — not understanding that the baseline for measuring the problem was off the mark to begin with. Not grasping the scale of the challenge, taxpayers may even become fatalistic and think interventions are going nowhere and should be abandoned.

Bad data and poor understanding of the issue of homelessness fuels a vicious cycle, one that has arguably entrapped King County for years, if not decades.

Integrating data sources provides more accurate counts

People experiencing homelessness remain invisible for many reasons: some camp or live in vehicles out of the public view, while others sleep on couches or in garages, moving from one precarious short-term housing situation to the next. Even people seeking out services may not reveal they are struggling with homelessness, further complicating attempts to collect accurate data.

Starting in 2018, King County invested in data infrastructure to connect several key county data sources for understanding homelessness. In addition to the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) mentioned earlier, King County also integrated the Health Care for the Homeless Network (HCHN) and Behavioral Health and Recovery Division (BHRD), among other sources, into its data collection.

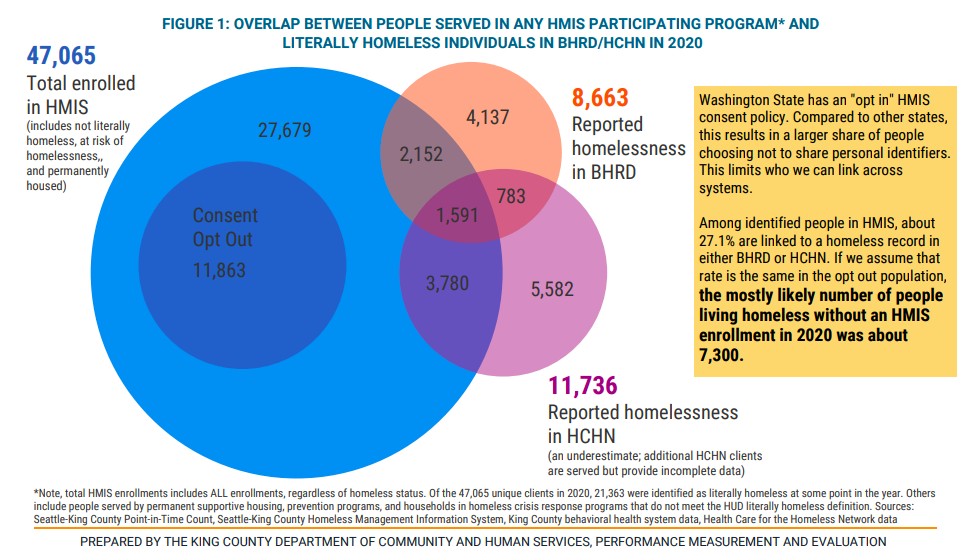

Drawing on multiple data sources has allowed King County to identify people experiencing homelessness who would remain invisible during PIT Counts. Crucially, the integrated approach also helped to expand the data to include people who opted out of the HMIS consent policy. Washington State is the only state that requires local providers to ask people if they agree to sharing their personal information when receiving services for homelessness. Nearly 30% of people receiving services opt out of sharing this information.

In order to create an estimate of how many people experiencing homelessness may have elected to opt out of the HMIS consent policy, a study was undertaken linking HMIS data to a homeless person’s record in either the County’s HCHN (healthcare) or BHRD (behavioral health and recovery) systems. Applying that percentage to the 30% people who elected not share their personal information with HMIS programs resulted in the number of people estimated to have experienced homelessness in 2020 increasing by 7,300, or 22%.

Beyond opting out of the HMIS consent policy, there are other reasons why people experiencing homelessness remain invisible. It is well-known that affordable housing is scarce in King County and wait times are long. These realities may discourage people from seeking services when they are in need. Behavioral health is another major contributing factor with people who have high behavioral health needs more likely to not seek services or encounter barriers to entry or assessment when they do. Geography also plays a role — many suburban and rural areas may lack many homeless services. In this instance, people experiencing homelessness are more likely to be identified when seeking to access healthcare, making it vital to integrate this information into the larger system to ensure they are counted.

Data reveals demographic differences in service use

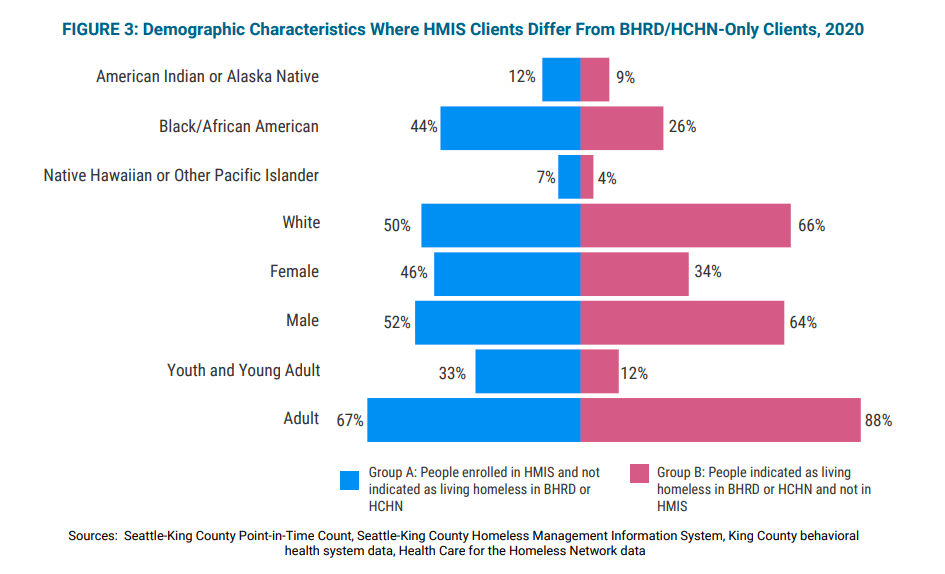

The ability to integrate data has also allowed King County to develop a more accurate picture around the demographics of who uses different homeless services. To do so, the analysts identified two main groups. Group A included people who were identified in the HMIS (Homeless Management Information Service), but were not identified as homeless in either County provided healthcare or behavioral health and treatment services. For Group B, the opposite was true — people were identified as homeless by healthcare and behavioral health and treatment services, but were not entered into HMIS.

While many differences in service use appeared, most striking was the fact that White male adults identified as homeless by healthcare and/or behavioral health and treatment services were the least likely to be included in HMIS data, leaving them uncounted by former data collection techniques. As a whole, King County has expressed the need to better understand differences across demographic groups in program access in order to improve outreach and services.

Next steps

Now that it has more comprehensive data available, King County plans to put it to use by improving homeless program operations and coordination, identifying gaps in services, more accurately evaluate promising new programs, and improving program outcomes and equity. King County hopes this will yield better insights into the factors that drive the homelessness crisis and identify new opportunities to improving the use of existing resources, especially with the new Regional Homelessness Authority guiding the efforts.

But, this new data also should incite King County — and the cities within it — to take a hard look at their budgets and assess whether they’re investing enough to address homelessness. If we were missing at least 20% of homeless people in previous counts, spending must be increased to meet the real need. In his recent budget proposal, Governor Jay Inslee called for investing $815 million in addressing homelessness, more than double than what he had requested for 2020. His request moves in the right direction; now armed with new data, other levels of government should also opt to invest more in getting people into housing.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.