A bill allowing single-stairway “point access block” buildings would enhance housing and neighborhoods.

On February 2nd the Washington State Senate held its first hearing on SB 5491, a bill that adds a powerful tool to the state’s housing arsenal by permitting point access blocks — compact single stair buildings with dwellings centered around a stairway and elevator core. These buildings have a single point of access vertical corridor leading to the upper levels, hence the name.

Point access blocks are already allowed under the International Building Code (the model building code adopted in most states) as well as the Washington State Building Code (a modified version of the IBC), up to three stories. However, Seattle has modified its version of the Building Code, allowing point access blocks up to five stories for purely residential, or six-story mixed-use buildings. In order to do this, planners must meet a whole host of conditions including sprinklering the building, limitations on travel distance, fire-rated doors and assemblies, and corridors separating units and stairways.

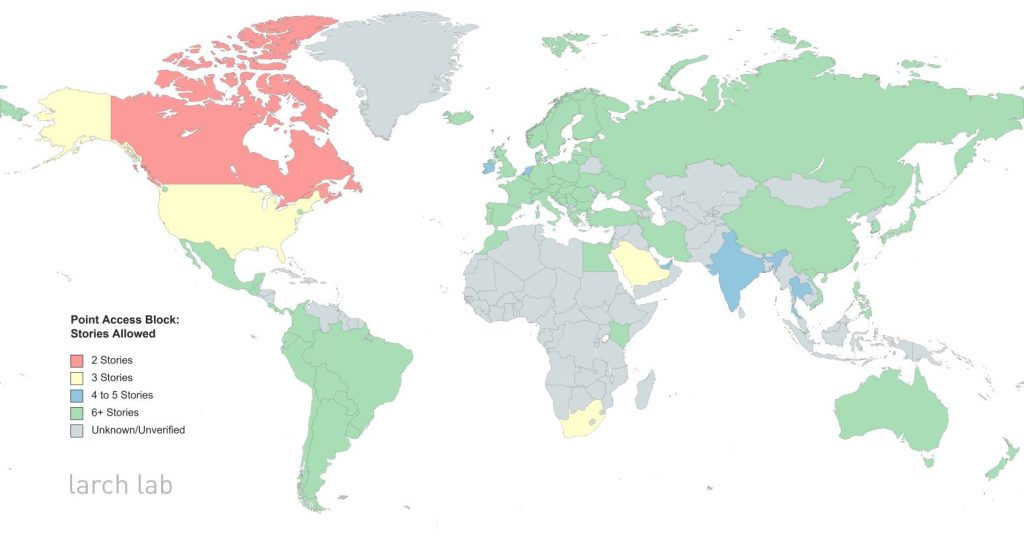

This bill, sponsored by Senators Jesse Salomon, Sharon Shewmake, Noel Frame, Marko Liias, and Derek Stanford, would allow Washington cities that have adequate fire flow, to adopt Seattle’s code provisions for point access blocks. These types of buildings six stories and taller are legal and common in most of the world.

From my research and work experience in Germany and the U.S., I can say without a doubt that the typical multifamily development in the U.S. is rare in other countries. I believe that allowing taller point access blocks statewide will unlock more small-scale development without the need for parcel assemblage, a process which increases costs and time of development. It could also unlock better development — especially between the ‘missing middle’ and mid-rise scales. This means more affordable housing, more climate adaptive housing, more multigenerational and family-sized housing.

Point access blocks offer a greater variety of architecture, as well as unit types and sizes, even on small urban lots. Floor plates tend to be very flexible, with a higher proportion of units ranging from two- to four-bedrooms. Current land use and building code requirements effectively mandate a double loaded corridor building, with a central hallway accessing units on either side of it. These buildings are largely studios and one-bedroom homes, and it is very difficult to get family-sized dwellings in them. Economically, a 3-bedroom unit is effectively competing against the income of three or four studios. Even rarer are 4-bedroom or multi-generational units — but these very homes are possible with point access blocks, and incredibly common in Germany and Switzerland. This seems to be a paradox, but it is directly related to the limitation on the number of units per floor — incentivizing larger units to maximize built floor area.

There are also several environmental benefits with point access blocks over typical development. Since the units tend to be situated either on a corner, or through running (that is, having windows on opposite sides of the unit), they have better daylight and the ability to better cross ventilate. This issue will become more of an imperative in a warming world, where the units found in typical construction today are extremely susceptible to overheating. Point access blocks are also compact buildings with narrower and more efficient floor plates. This reduces the embodied carbon of construction, as well as overall cost. It also allows for more space on the lot to be utilized for courtyards or open space — a dwindling amenity currently.

I would love to see a path to seven- and eight-story point access block buildings since these are heights that not only play well with mass timber, but also keep buildings under the ‘highrise’ threshold, which rightfully requires additional conditions and life safety protections. I believe this height would allow for better balancing of construction and elevator costs for small lot development as well.

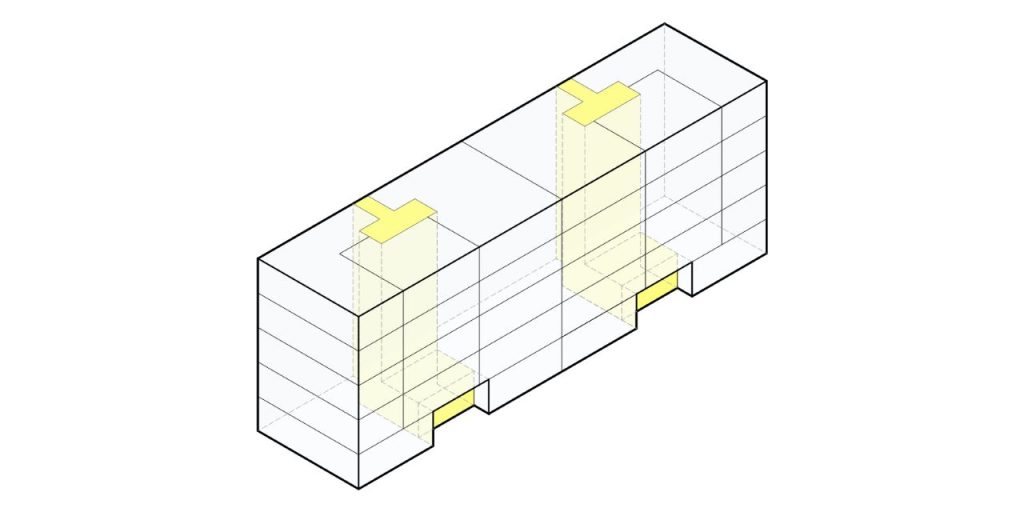

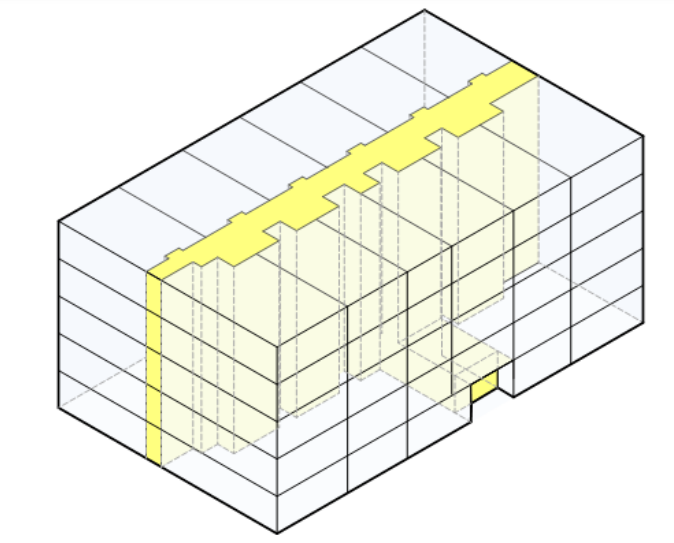

The proposed Senate Bill also matches Seattle’s requirement of allowing at most two point access block conditions per parcel. I could point to a multitude of projects in European countries with lower fire death rates that do not limit the number of point access blocks. This allows them to be connected in series, to create much larger buildings, or even perimeter block development while maintaining the livability and environmental benefits of this form of vertical circulation: better daylight, more family-sized units, and cross ventilation.

Regardless, this bill is a step in the right direction. It would enable more housing schemes found throughout the world. It will unlock abundant development on small lots. It would allow for stacked fourplexes or four-story eightplexes in areas outside of Seattle, where land costs are significantly lower.

The U.S. (and Canada) are extreme outliers when it comes to allowing these types of buildings, despite numerous other requirements that are not required for low- and mid-rise housing in European countries, such as fire sprinklers. There has been significant interest the last few years on changing this – with an article in Slate, the Niskanen Center, a recent panel at the UCLA’s Lewis Center, and numerous Cities and States exploring paths for reform. I also recommend Conrad Speckert’s Master’s thesis on Single Stair Buildings, which visually documents the regulatory and design differences on his website, Second Egress.

Fire doesn’t burn differently here than in Switzerland, Vienna, or Japan — but our buildings and subsequent multifamily housing certainly is designed like it does. Point access blocks are the fundamental building block of cities the world over — whether in new construction or existing. That fine-grained nature of cities that urbanists, planners, and politicians claim to love, but it is effectively illegal under our building codes. With the right framework, they can be used on a variety of scales, from small infill sites to large perimeter blocks. They also increase opportunities for small property owners, homeowners, small developers, community land trusts, and coops to meet today’s housing needs — groups typically unable to do large scale, well-capitalized projects.

Legalizing taller point access blocks starts the conversation toward enabling all of these benefits.

Sign in as pro and submit a comment in favor of SB 5491.

Mike is the founder of Larch Lab, an architecture and urbanism think and do tank focusing on prefabricated, decarbonized, climate-adaptive, low-energy urban buildings; sustainable mobility; livable ecodistricts. He is also a dad, writer, and researcher with a passion for passivhaus buildings, baugruppen, social housing, livable cities, and car-free streets. After living in Freiburg, Mike spent 15 years raising his family - nearly car-free, in Fremont. After a brief sojourn to study mass timber buildings in Bayern, he has returned to jumpstart a baugruppe movement and help build a more sustainable, equitable, and livable Seattle. Ohne autos.