More than 2,000 units of affordable housing in King County alone could stop being affordable by the end of the decade because of the expiration of federal tax credits that locked in affordability for 30 years.

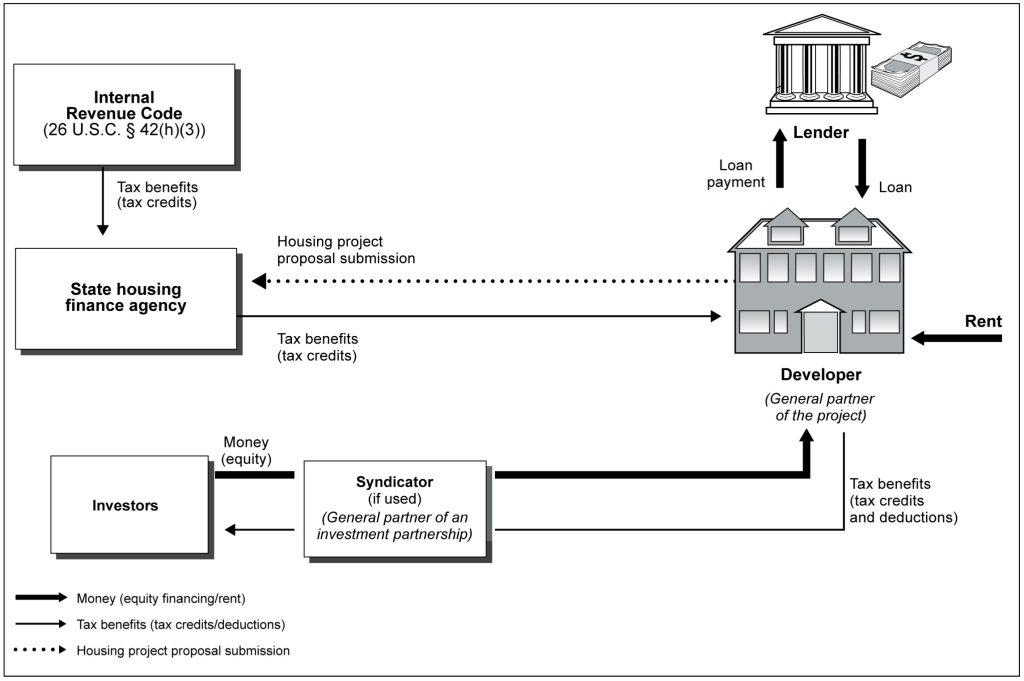

The Low Income Housing Tax Credit program (LIHTC) provides financing options to developers in exchange for below-market rents. The credits are often used to finance the construction of properties, but can also be used for maintenance and acquisition of existing buildings.

However, they expire after 30 years, and the IRS stops auditing them after 15, leaving the fate of thousands of affordable housing units up in the air. Owners of the buildings can sell to a for-profit owner, for instance, or otherwise mark up the units to market rate.

While King County-based nonprofit organizations — which the state refers to as “mission-driven” entities — with tax credits expiring this decade say they have no intention of hiking rates, the threat of the credits’ expiration has had real-world consequences in other places.

In March, Oregon Public Broadcasting reporter Alex Zielinski wrote about a move by Washington County to buy the 172-unit Woodspring Apartments complex that houses many low-income seniors in order to preserve affordability — the tax credits expired in 2021 and company that had purchased the building five years earlier announced that year that it would be hiking rents.

Organizing led by tenants and supporters caught the attention of local government leaders who said they would intervene to buy the property. While Woodspring may be saved, it was a one-off deal, leaving thousands of other properties across Oregon in limbo.

According to Washington state records, 24 properties totaling 2,071 units will hit the 30-year mark between 2023 and 2029 in King County alone. Statewide, that figure leaps to 5,531 units.

The LIHTC program was established through the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Given that credits have a 30-year timeline, the state doesn’t have much experience in these projects expiring. About a dozen expired in 2022, and the Washington State Housing Finance Commission (WSHFC) expects a similar number this year, said Melissa Donahue, manager of Asset Management & Compliance with WSHFC.

In some cases, these units are not going to come back, Donahue said, but WSHFC mainly lends to those “mission-driven” housing providers.

“The folks that are mission-driven housing providers, their goal is to keep all these projects affordable housing for as long as they can,” Donahue said.

DESC is one of the largest housing and shelter providers in the region, and it has used tax credits in its projects. However, it’s never had credits expire, wrote Claire Tuohy-Morgan, communications and community relations manager with DESC, in an email.

That will change this year: Tax credits on the Union Hotel building — with 50 units of affordable housing located in downtown Seattle — will expire on Dec. 31, 2023.

Other funding sources for the building outside of the tax credits mean that the Union Hotel has to stay affordable for 50 years, which is another two decades from now.

“As a mission-based nonprofit, we have no interest in raising the rents, evicting tenants into homelessness and operating a market rate apartment building,” Tuohy-Morgan wrote. “If we were ever to sell a building after the tax credits expire and pay off the loans, removing the rent restrictions, it would not be done lightly.”

The organization expects that it will be able to negotiate extensions or get new loans on the buildings to keep them available to low-income households, she wrote.

Sales to outside organizations aren’t frequent, but they do happen. At least five buildings belonging to nonprofit housing providers that were funded with tax credits have been sold before the 30-year credit period was up, according to research by Camille Gix of House Our Neighbors!, a project of Real Change that campaigned to pass the I-135 social housing initiative in February. (Disclosure: Gix conducted this research while holding an intern role in the Advocacy Department.)

So, how do LIHTCs work?

Warning: This is about to get wonky.

The tax credit program is made up of two funding types: the 9% program and the 4% program. The 9% program is pure tax credits, usually used to build or rehab a building. If a housing provider uses 9% LIHTCs, the bulk of its funding is coming from tax credits.

The 4 percent program pairs LIHTCs with tax-exempt bonds, another financing tool. This can get complex. According to the 2023 WSHFC policy document for the program, there is no federal cap on 4 percent tax credits if more than half of a project is financed by bonds issued by the commission.

However, while the tax credits aren’t limited, there is a cap on the amount of bonds that the state will issue, determined by the state’s population. Of that bond cap, 42% can go toward housing.

When multifamily bonds are oversubscribed — as they have been for many years — the commission announces a “bond round,” which means competition for the bonds. In 2022, 21 applications requested allocations totaling $561 million, but only 10 of those received allocations totaling $249.3 million.

The federal government does limit the amount of credits available through the 9% program. In the November 2022 application round for 2023 9% credits, $32.3 million in requests were chasing $16.7 million in credits, according to the 2023 allocation list.

Most housing finance authorities use a pretty even mix of the two programs, but WSHFC’s mix of 4 and 9% LIHTCs leans a bit more heavily than most toward the 4% program, Donahue said.

Finally, a twist: Tax credits are sold to investors, because most nonprofit organizations don’t have sufficient tax liability to make them worthwhile. That’s how the credits generate cash flow for the projects.

The need for affordable housing in Washington state means that more projects are chasing more credits and bonds than are available.

Every year, the National Low Income Housing Coalition produces a report called “The Gap,” which looks at the difference between the supply of and demand for affordable housing. According to the 2023 report, issued in March, Washington state needs 174,821 units of housing affordable to people with extremely low incomes — 30% or less of the area median income (AMI) — and 220,225 units of housing affordable to people at 50% of AMI or below.

While the potential loss of units may seem dire, Donahue cautioned against alarm.

Subsequent rounds of LIHTC allocations mean that more units will come online even as some come off the books, and many will remain affordable either because mission-driven housing providers ensure it or housing providers go through a “rescindication process,” meaning they receive another allocation to rehab an aging building.

This article was produced in partnership with Real Change News, where Ashley Archibald is the editor.

Ashley Archibald

Ashley Archibald is the editor of Real Change News, a nonprofit journalism outlet covering economic and social justice issues in Seattle and beyond. She can be reached at editor [at] realchangenews.org and on Twitter at @AshleyA_RC.