FAME Housing is building an affordable housing development like no other in Seattle’s Central District

For over 50 years, Bryant Manor has provided affordable housing to families in an amenity-rich location in Seattle’s Central District. Part of First A.M.E. Housing Association (FAME Housing), Bryant Manor is a significant site for many members of Seattle’s Black community.

“Everybody has memories of Bryant Manor,” said Shawn Abdul, Executive Director of FAME Housing in an interview with The Urbanist. “It’s been known throughout the Central District as a haven for folks.”

Tucked next to a dynamic urban park, walking distance to elementary, middle, and high schools, and located a short bus ride to Downtown Seattle, Bryant Manor is known as a place that nurtures creativity in people. Notable Seattleites like hip-hop legend Sir Mix-A-Lot and Jite Agbro, a mixed media artist who created an immersive exhibit about Bryant Manor, have called the development home.

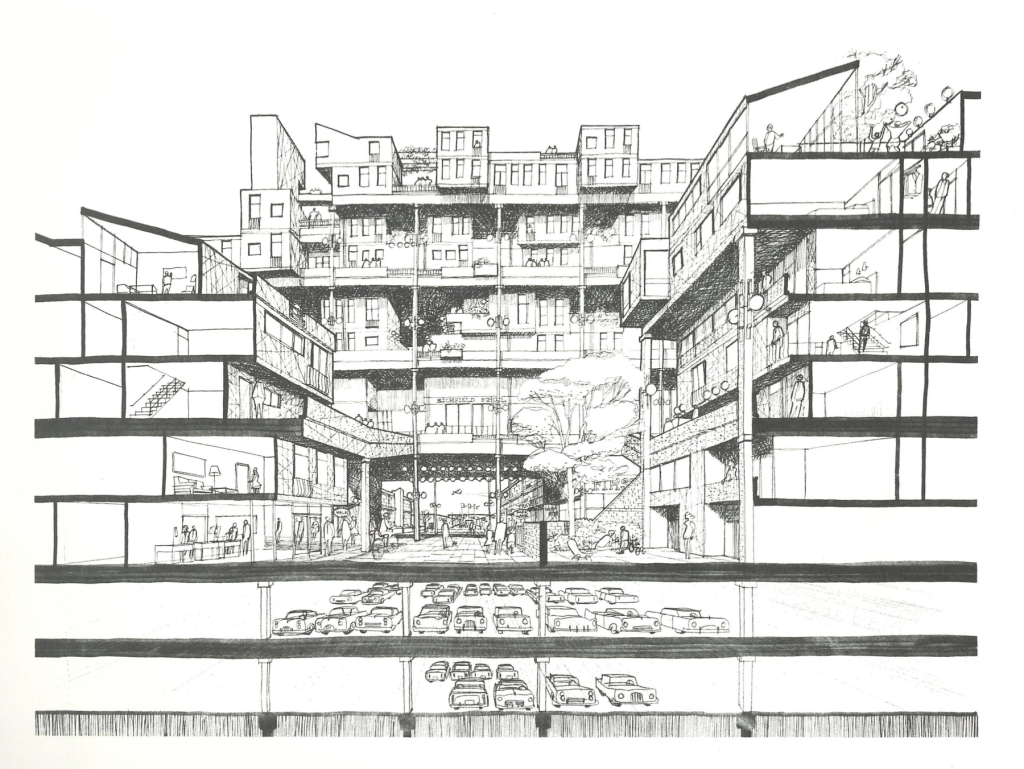

Now with the first phase of construction underway that will increase Bryant Manor’s size from 58 to 246 homes, the development is set to become a haven of affordability for more families than ever — potentially 1,200 people may call Bryant Manor home in the future. That’s because many of the units will have two, three, and four bedrooms, something uncommon in most affordable housing developments in Seattle.

“Our goal is to recapture Bryant Manor as a beacon for the Black community to come back to Seattle and come back to the Central District in particular,” Abdul said.

Marcus Price, a FAME Housing boardmember and advocate for the project, echoed that assertion: “Bryant Manor has always been viewed as an anti-gentrification tool. It has always been the goal of the board to help bring the kids back to the Central District in an affordable way.”

The fight for family-sized housing

Achieving this goal proved to be a challenge for FAME Housing who worked for 15 years to make the Bryant Manor redevelopment project a reality.

It’s not a secret that while it’s difficult to secure affordable housing in Seattle, it is even harder to find family-sized affordable housing. Because many affordable housing developments’ competitiveness for funding hinges on how many units will be created, developers angle toward plans that emphasize the creation of studios and one-bedroom homes. But FAME Housing wanted funders to understand that it is just as important to assess how many people will be housed by a project.

“We held fast there for the fact that our community, particularly the Black community, needed those larger size units because Black families in King County tend to be larger, two times larger actually, than their White counterparts,” Abdul said. “Therefore, housing that the city and the county and the state had been providing up to that point, which was typically studios and one bedrooms, would have never actually been able to serve the Black community properly.”

“So, we went on a kind of an advocacy crusade with all of the public funders, and we encouraged them to change the way that they look at their measurements,” Abdul explained. “Instead of saying, look how many units we’ve opened, we said look how many people we’re housing. Because if you put out 10 one-bedroom units, technically according to occupancy standards, you can only put in about 20 people into those 10 units. But if you had 10 units with four bedrooms, you’re housing way more people. It justifies the cost, as opposed to just saying, let’s build smaller units because they’re easier.”

When both phases of construction are completed at Bryant Manor, there will be 36 one-bedroom, 119 two-bedroom, 78 three-bedroom and 14 four-bedroom homes spread over 72,000 square feet of floor space. Abdul hopes that some of the one-bedroom units will house older family members, allowing for intergenerational living to flourish on the site. He also hopes that a small number of units will be available to sell as condos offering affordable entry into home ownership, but the details still remain to be worked on at this point.

Historic legacy and a commitment to the future

Bryant Manor was dedicated to the memory of Harrison J. Bryant, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church in 1972. While the name recognizes the importance of church elders in Bryant Manor’s history, their role is by no means confined to the past.

Ron Flynn, who was involved in FAME Housing for more than 40 years, including serving as board president, was a passionate advocate for ensuring that the ground floor of the new Bryant Manor features an early learning center. While Flynn passed away in 2022, his memory will live on in the Ashé Learning Community Center that will provide childcare and early learning for the building’s youngest residents when it opens as part of the first phase of construction. The wing of building in which the early learning center will be located will be named in Flynn’s honor to recognize his commitment.

Price attributed his motivation for becoming involved with the Bryant Manor project to the “community forefathers who said, ‘Let’s use our resources to provide for others.’”

“The elders were a real testament to missionary work,” Price added. “I remember one of them would come to our meetings with his walker in the rain. But that’s how he was committed, and his commitment motivated me. I’m thankful that I was able to witness all these great people.”

It was these elders who seized the moment decades earlier to make the original Bryant Manor a reality. In the late 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. government was interested in using factory production to quickly and affordably build quality housing for people of all income levels. To spur development, HUD created a program called, Operation Breakthrough, which sought partners like General Electric and Boeing to test out new homebuilding technologies and techniques.

Bryant Manor was Boeing’s attempt to enter into housing production using board-formed concrete panels manufactured in factories. The plan was for Bryant Manor’s concrete and wood townhouse model to be reproduced elsewhere, but like many of the developments created as part of Operation Breakthrough, it did not prove scalable. Bryant Manor marked the beginning and end of Boeing’s foray into housing.

FAME Housing, however, endured as an affordable housing provider in Central Seattle, even as the city and neighborhood changed in significant ways. As more and more immigrants arrived in Seattle, especially from East African countries like Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, the demographic profile of residents at Bryant Manor shifted too.

In addition to being a place for families, Bryant Manor has been where “new immigrants came and felt comfortable,” Price said.

Abdul estimates that today Bryant Manor’s residents are predominantly East African immigrant families. “The Black community has been a cornerstone of Bryant Manor throughout the years, but with that being said, we also continue to embrace the family we’ve found since then. Bryant Manor is highly diverse, and we love those families.”

Abdul said that they wanted to make clear that the current community understood that they could have a home in the future development.

“We told them that this work is to continue to embrace you and embrace other people like you. We have plenty of space for everyone,” he said.

Supporting residents through the redevelopment process

Prior to construction, residents of the first buildings to be demolished were moved at no cost to themselves to comparable housing in the area for which they continue to pay the same rent they paid at Bryant Manor. The relocation was managed by Housing to Home, a company that handles affordable housing residents’ relocation in a manner that complies with the Federal Uniform Relocation and Real Properties Acquisition Act of 1970 and other applicable local, state, and federal guidelines.

“Of course it was a challenge finding housing for all the residents given Seattle’s competitive market,” said Hannagh Jacobsen, CEO of Housing to Home in a conversation with The Urbanist on her company’s work, “but our staff were able to push through and find housing that met the residents’ needs, not just for [unit] size, but also factors like ADA accessibility. I’m really proud of their work.”

Residents are also checked in on regularly to make sure things are going smoothly for them in their current housing during this transitional time. Once the new homes are ready, Abdul expects residents will take advantage of their right to return to the new Bryant Manor. If not, FAME Housing will need to pay them financial compensation in accordance with federal guidelines. These rules, part of the Uniform Relocation and Real Properties Act, were created to protect Section 8 renters from displacement in the event of housing renovation or redevelopment.

As executive director, Abdul also has big plans for FAME Housing’s future with Bryant Manor. The plan is in the next 15 years for FAME Housing to become fully the owner, manager, and sponsor of the development. FAME Housing also plans to update its other existing affordable housing, the Imperial and Texada apartment buildings in Capitol Hill, and to continue to expand its housing portfolio as opportunities arise.

“I think that’s just such a true scrapper story,” Abdul said. “We are an organization that existed for 50 years, but only a small segment of this general Seattle community knew who FAME housing was. To break out of the gate and kind of have all this come to us at one time, it’s been a challenge, but it’s been such a rewarding challenge to see the growth that we’ve had.”

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.