An agency report obtained by The Urbanist lays out three key scenarios to implement fare gates with the goal of driving up fare compliance and revenue.

Fare policy has a been a hotly contested issue at Sound Transit for the past few years, due in large part to concerns with punitive penalties and racially disproportionate impacts of the old fare enforcement paradigm. That led Sound Transit to radically adjust its fare enforcement system by being more forgiving toward violations, focusing on compliance education, and providing a friendlier face to the system with fare ambassadors, but it hasn’t been supported by all agency boardmembers.

Repeated calls for tougher consequences and use of fare gates due to high fare evasion rates have come from various corners. To that end, Sound Transit has quietly been evaluating use of fare gates at some or all of its rail stations.

Last December, a third-party report prepared for the agency offered a look into the pros and cons of implementing fare gates. The report strongly suggests that fare gates could provide a high rate of return on investment. That’s because fare gates would dramatically push down fare evasion on Link and help Sound Transit raise more revenue that it’s otherwise unlikely to realize.

Implementing fare gates, however, may be easier said than done. Gating stations after they have opened can require considerable custom design to fit and trigger expensive retrofits to meet safety codes. Fare gates also demand some forethought for how they will be managed, integrate with existing fare payment systems, and maintain station flow.

Fare gates could offer a good return on investment

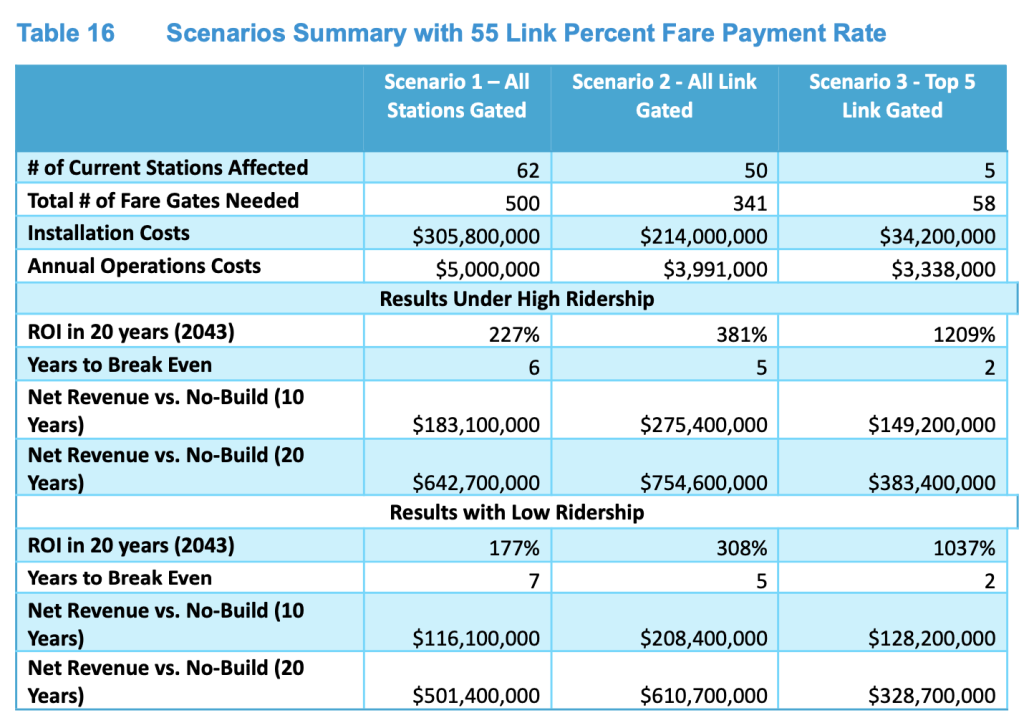

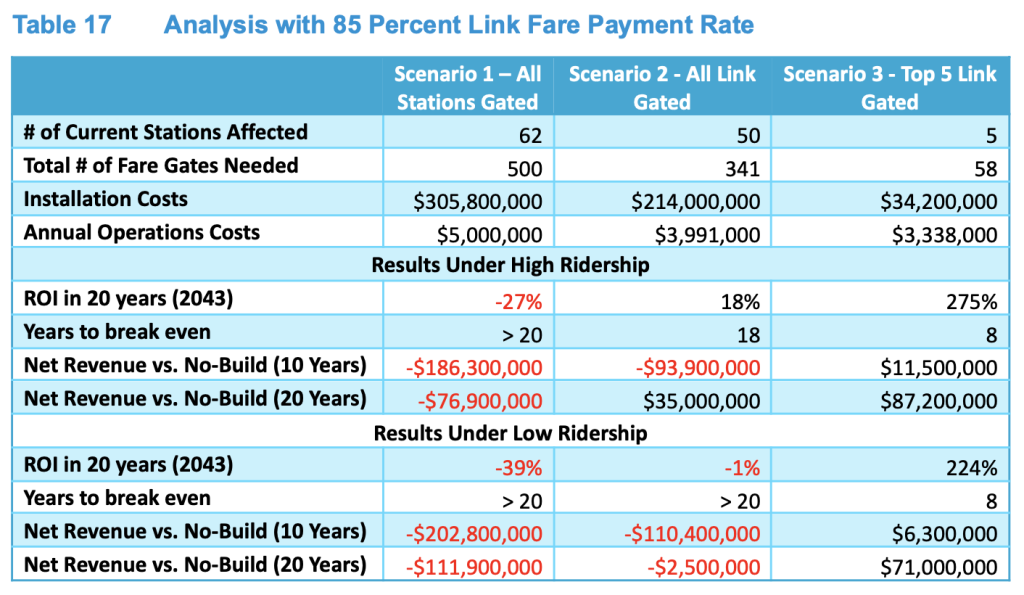

The fare gate report details a dozen cost-benefit scenarios for fare gate deployment. Scenarios are modeled based upon several assumptions, including baseline Link fare payment rates (tested at 55% and 85%) prior to fare gates, high and low ridership projections, and gating all or some Link and Sounder stations. Underpinning these scenarios are several other key assumptions, including the projected fare payment rate with gating, a reasonable annual discount rate on the future value of money, a generous construction cost contingency rate, and some fare gate replacement after 10 years of operation. Fare gate payment rates are assumed to be 95%, which is in line with peer systems’ real-world experience.

Revenue projections from the model should come with a bit of caution as agency staff flagged issues with ridership calculations earlier this year. But directionally, the scenarios paint a fairly clear picture on potential return on investment (ROI) from fare gates.

The report has baselined scenarios on a current fare payment environment, modeled at the agency’s 55% fare compliance estimate. The study found gating the five busiest Link stations would deliver the best ROI on a percentage basis. The high ridership scenarios suggest that near-term net revenue could range from $149.2 million to $275.4 million, depending on how many stations are gated, and the longer-term net revenue could reach as much as $754.6 million. The low ridership scenarios could still provide significant net revenue anywhere from $116.1 million to $208.4 million in the short-term and $328.7 million to $610.7 million in the long-term. Across scenarios, the break even point could be as short as two years, with the longest pay-back period being seven years, according to the study.

Scenarios were also tested at an 85% fare payment rate environment, prior to gating. The results of that are far less impressive with only scenarios gating the five busiest Link stations providing a marginal value for the investment.

Though fares make up a relatively small share of Sound Transit’s annual revenue, they are an important source of funding that would be difficult to replace in the agency’s long-range finance plan, which funds both operations and capital expansion. Fares are currently estimated to fund around $5.5 billion of the $148.2 billion plan through 2046. Estimates made prior to the pandemic for the plan had projected $9.3 billion to $9.5 billion in fare revenue, but that was in a time with a much higher fare compliance rate and more robust ridership for the size of the transit system then.

Since the pandemic, fare evasion rates on Link have climbed; agency estimates peg it at about 45%, translating to a 55% fare payment rate. Rosier numbers calculated via the new fare ambassador program found that fare evasion rates hovered around 13% earlier this year, but that program doesn’t seem to be capturing an accurate fare evasion rate, as the agency has continued to cite the 45% estimate.

In short, if the real fare compliance rate is only around 55%, then fare gates could be a good investment for the agency. If the figure is closer to the rate observed by fare ambassadors, it would make a poor investment. Accurate fare compliance data will be essential to the agency ensuring their decision is fiscally prudent.

Beyond higher rates of fare payment and more revenue, the report notes what it considers potential secondary benefits of fare gates. Those include regulating passenger flows onto platforms, collecting better ridership data, improving security, and reducing loitering at stations.

Implementing a fare gate system would require careful consideration

Sound Transit has three general types of stations: at-grade stations, underground stations, and elevated stations. The fare gate report suggests that installation of fare gates at elevated stations is generally easier since they typically have more space under and around them to place fencing and line up gates. Underground stations, particularly the older ones, could be more challenging given the tighter space constraints of them and existing structural elements. And at-grade stations present a bigger challenge to retrofitting for fare gates since they often allow access at both sides of a narrow platform in difficult-to-control environments.

If Sound Transit elects to install fare gates, one option that the agency could pursue is starting small and focusing on just the highest ridership Link stations, the report said, following the strategy of systems like LA Metro and San Francisco’s Muni Metro. Targeting stations like Westlake, Capitol Hill, and Northgate would provide a very high ROI, as evidenced in the aforementioned tables. The agency could, in time, strategically expand fare gates to other locations if deemed economically beneficial or as part of multi-phase rollout.

Fare gates aren’t without their flaws though. “Interviewees noted that these physical barriers are not impenetrable,” the report said. “Riders who seek to evade fare payment do so by jumping gates, tailgating (following someone inside), pushing gates open, and entering through emergency exit zones.”

Many American transit agencies are in the process of hardening their fare gates in response to increased fare evasion rates, a cycle that the report warned could become recurring to respond to new ways riders evade paying fare. San Francisco’s BART, Washington DC’s Metrorail, and the New York City Subway are examples of this with ongoing efforts to install new equipment that makes it more challenging to evade their systems.

The fare gate report also warned that by installing fare gates at just a few stations, there is a risk for spillover fare evasion to nearby stations without fare gates. Consequently, expansion of gating may quickly become a priority to stamp out elevated fare evasion rates at those other stations, its own form of cyclical fare gate investment.

Transit agencies using fare gate systems must have robust operational strategies, the fare gate report said. Maintenance response times, for instance, need to be quick. Inoperable equipment can become a fixed barrier to passenger flows and a safety risk in the event fare gates are needed for emergency egress. Inoperable equipment can also be an opportunity to defeat fare payment if gates are stuck open. Customer service is another operational imperative. Invariably, there will be times that riders need help in passing though gates, so having something like a call button response or fixed station agent staffing strategy is critical to maintain a positive rider experience culture.

If Sound Transit does implement a fare gate system, it will also want to avoid the rider experience blunders other transit agencies have made in the past. Vancouver and New York City both offer cautionary tales.

In 2016, Vancouver’s TransLink launched its fare gate system with an equipment configuration poorly designed for accessibility, requiring station agents to help tap fare cards for disabled riders to pass through. The agency has partially rectified this through its universal access program, but the situation was bruising to TransLink’s reputation.

And in the 1980s and 1990s, the New York City Subway was focused on hardening fare gates, giving stations outfitted with them a very imposing and threatening appearance. That sent a very negative and unwelcoming signal to the public about the state of the transit system in an era when the city was already poorly portrayed because of high crime rates.

Upfront fare gates costs can run high

As the agency weighs fare gates, costs are certain to be an important consideration.

Upfront costs for fare gates can be quite substantial, as the aforementioned tables bear out, but the fare gate report tried to put a finer point on quantifying unit costs. “Fare gate units ranged in cost from $10,000 on the low end for older model turnstile gates without integrated fare media/fare validation to $50,000 on the higher end for modern paddle gates with integrated fare validation systems,” the report said. “Vendors emphasized that installation costs might be lower with a single product type chosen for all stations so as to streamline the install process through efficiency.”

Costs aren’t just tied up in the fare gates themselves, however. Fencing, wiring, retrofitting, security cameras, and more ticket vending machines all add to the effective cost. Because of that, the report estimates on the low end that installation of fare gates at the five busiest Link stations would cost $34.2 million for 58 gates, an effective cost of $590,000 per gate. Gating all rail stations could cost about $305 million for 500 fare gates, translating to a slightly higher effective cost of $610,000 per gate.

Ongoing operational costs though are projected to be fairly modest with yearly expenditures of $3.3 million to $5 million, depending upon the number of gates.

Whether or not fare gates will come to pass as a feature of Sound Transit’s rail system remains to be seen. David Jackson, an agency spokesperson, said that a briefing on the topic will come to the agency board early next year. Debate around pursuing station gating will surely be contentious among boardmembers and riders alike when that happens. But for now, the Sound Transit CEO isn’t expressing an opinion on the policy issue, declining comment to The Urbanist. So it’s unclear what position the agency will carry to the board beyond report findings.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.