One of the “fatal four” behaviors seen in traffic crashes is becoming widely seen on Washington roadways, but fixes will likely need to happen at the local level, not in the legislature.

In the fall of 2018, the City of Mercer Island and the Mercer Island School District celebrated completion of a brand new safe routes to school roadway improvement project at its new Northwood Elementary School building. The first new elementary school constructed by the school district in 50 years, Northwood had opened its doors just two years earlier and sits along NE 40th Street, one of the busier roads on Mercer Island that residents and visitors use to travel between the two main north-south routes that transverse the island. It shares a campus with the city’s popular Mary Wayte Swimming Pool and is near several other public and private schools.

The road project, which was funded via a $500,000 grant from the state Transportation Improvement Board and some additional city dollars, rebuilt wider sidewalks along the street, added paint bike lanes along the street’s gutter, and refreshed the street markings along the corridor.

Yet in late 2022, when the Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC) visited Northwood as part of its statewide school zone speed survey and recorded driver speeds near the school, they found that 98% of drivers during the morning drop-off time were disregarding the flashing lights and signage indicating an active school zone, with a 20-mph speed limit. During afternoon pick-up, 89% of drivers were exceeding 20 mph. Beyond the signage and lights, the street’s new design doesn’t signal to drivers that they need to reduce their speeds.

Speeding epidemic hits nearly every school in the state

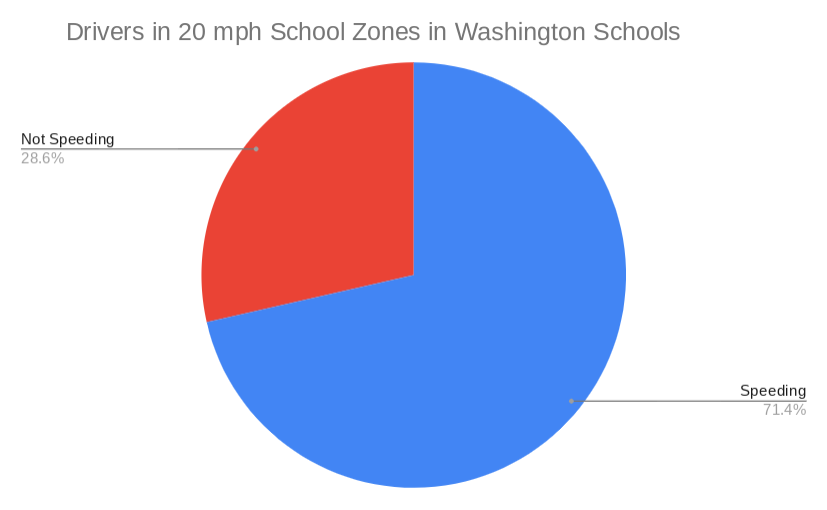

Northwood Elementary is far from alone. The commission’s statewide survey, conducted over the course of the 2022-2023 school year, found that more than 70% of drivers observed outside schools close to bell times were exceeding the posted 20-mph speed limit, with a majority of drivers observed staying under the limit at only around one out of every 10 schools. In all, nearly 20,000 drivers were observed as part of the study at nearly 100 schools, and the data paints a clear picture of the prevalence of speeding on Washington’s streets during the time periods when drivers are asked to be most aware of their speeds. You can explore the data for schools near you here.

The Washington Traffic Safety Commission (WTSC) has been trying to raise awareness of the dangers of speeding for years, with exceeding the posted speed limit included in its longstanding list of “fatal four” behaviors that are most frequently seen in deadly traffic crashes, along with drug and alcohol use, distraction, and a lack of wearing a seatbelt. In 2022, 31% of all traffic deaths in Washington involved a driver who was exceeding the speed limit, with pedestrians and people on bikes much more likely to be seriously hurt in a crash that involves a high-speed vehicle.

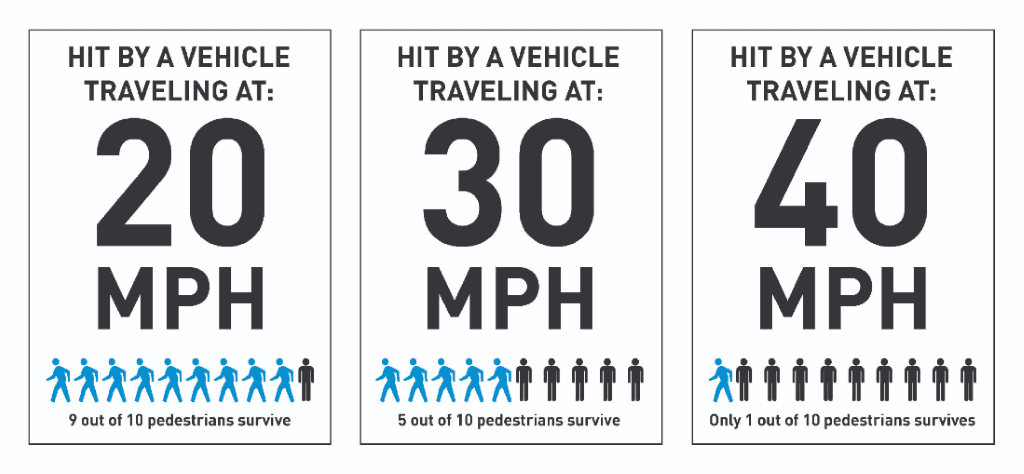

With children even more likely to be seriously injured in the event of a crash, the 20-mph speed limit immediately before and after school hours is a widely deployed remedy in communities large and small around the state. Data shows that the chances of a pedestrian being seriously injured at 16 mph is around 10%, and goes up to 50% when speeds exceed 30 mph.

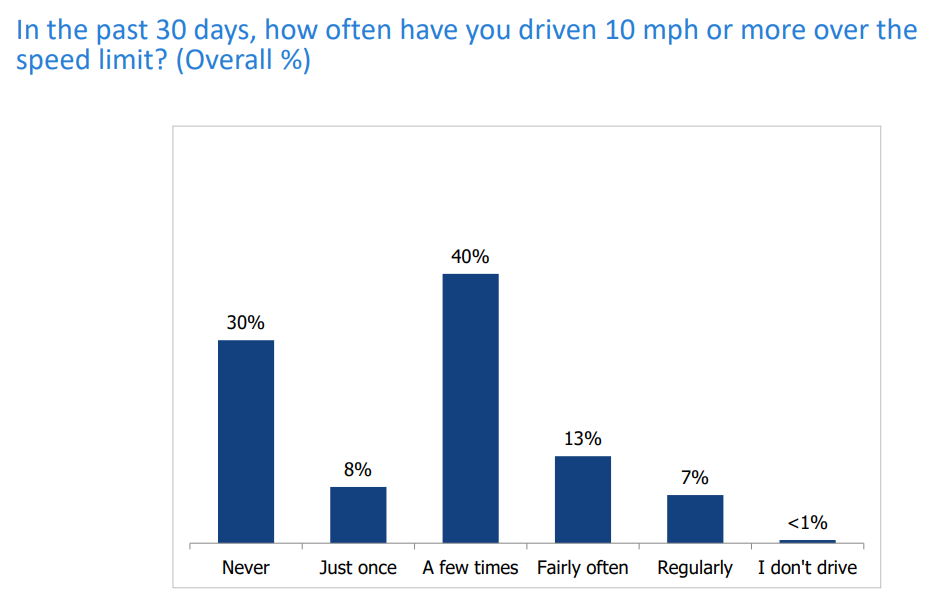

“It’s unfortunately one of the most acceptable high risk behaviors among the driving public,” Mark McKechnie, the safety commission’s director of external relations, told The Urbanist. “Generally, a lot of people admit to driving over the speed limit, even 10 miles over, and probably the majority of people will say they do it at least occasionally. And they seem to underestimate the risk that it poses to themselves or others. So I think we have a lot of education to do about the importance of reducing speeds.”

A WTSC survey conducted earlier this year found that out of nearly 11,000 Washington residents, only 30% of respondents said they hadn’t exceeded the speed limit in the last 30 days, with 20% saying they did so “fairly often” or “regularly” over that time frame. Driving 10 mph over the limit ranked lowest in a list of behaviors that respondents said was dangerous, with fewer than a third saying that it was.

“One of the additional alarming findings is that some of those people who are speeding through school zones are actually the people connected to the school,” McKechnie said. At Northwood Elementary, even out of the drivers who were specifically recorded as entering or exiting the school property, 70% were exceeding the 20 limit, with more than half going 25 mph or more. He pointed to educational campaigns that could specifically be aimed at local parents as a way to move the needle.

“If a principal or someone from the school can raise that issue, and generate the care and concern among parents and other people that are connected to the school and really emphasize the importance of slowing down and driving 20 miles an hour through their school zone, I think that that will be more effective in reaching one portion of that group that is driving too fast,” McKechnie said. “And then by slowing those people down, in a lot of places that’ll slow everyone down,” on roads where there aren’t any lanes available for passing.

But for the broader problem of widespread high speeds everywhere in the state, infrastructure solutions are likely to be much more impactful.

Automatic cameras make a difference

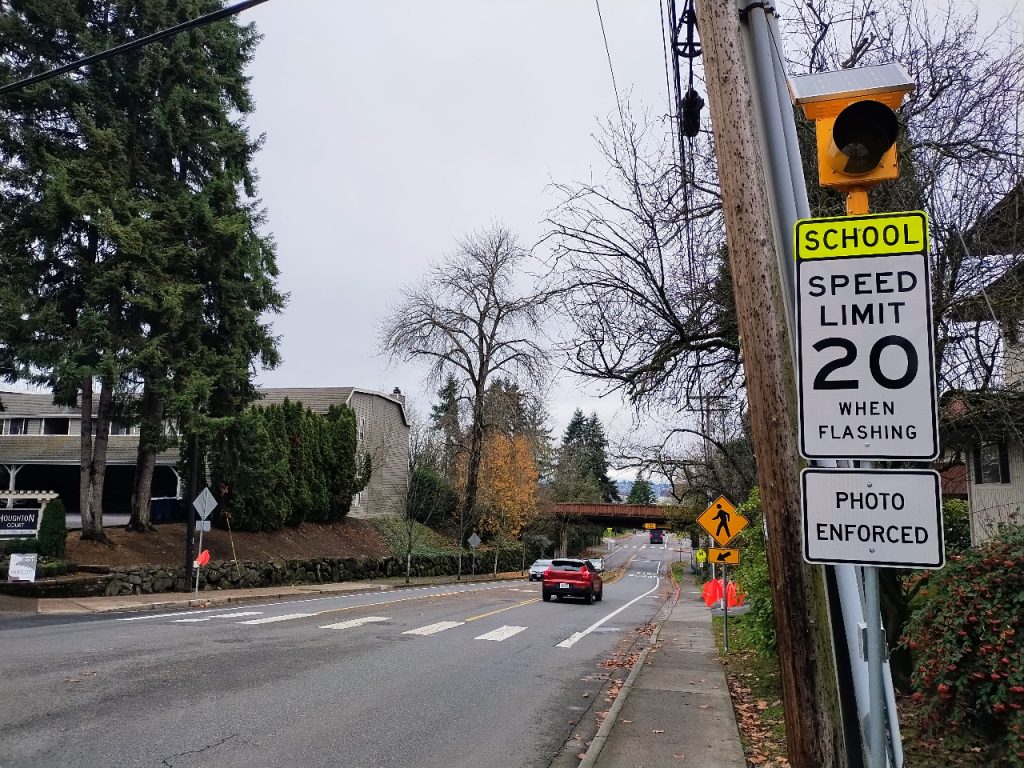

The school the safety commission visited with the highest rate of compliance to the 20 mph speed limit across the entire state — Showalter Middle School in Tukwila, where just 6.1% of drivers were exceeding the limit — currently has an automatic school zone camera in place.

This week, State Senate Transportation Chair Marko Liias (D-Edmonds) is visiting Finland, to get a better understanding of strategies Washington can use to reverse the escalating trend of traffic fatalities that the state is facing. Finland has deployed automatic camera technology fairly widely, with around 7% of the entire road network in the country covered by automatic traffic surveillance.

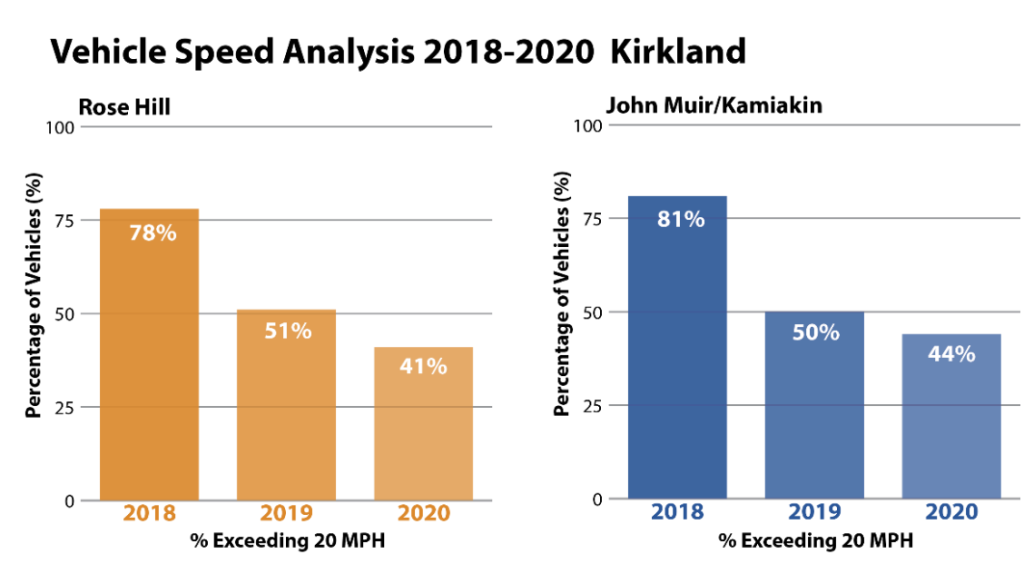

Several Washington cities have had success implementing school zone speed cameras, including Seattle and Kirkland. In Kirkland, which deployed a pilot program at two schools in 2019, the portion of drivers exceeding the 20-mph limit dropped by 37% by the next year. So far, 89% of drivers ticketed for speeding have not receive a second citation, something that aligns with Seattle, which has seen a 67% reduction in tickets issued at its camera locations since they started rolling out in 2012.

For many years, school zones were the only places where local cities could use speed cameras in Washington. But in 2022, the Washington legislature took steps to broadly expand the authority that local municipalities have to implement automatic speed cameras, allowing them to be used near more locations where pedestrians are likely to be present, like parks, hospitals, and school walk routes, and at locations where municipalities are seeing frequent crashes. But even though cities have the authority, nothing requires them to move urgently and to implement camera programs where they’ll be most effective — where driver behavior needs to change the most.

McKechnie told The Urbanist that the safety commission is not likely to recommend further expansion of camera authority in 2024, but instead will be pushing for legislation that can clean up the current requirements around cameras, making it more clear where cities can use them and potentially letting local jurisdictions keep more local funding for safety projects. In most of the places where cameras are allowed since 2022, like parks and hospitals, 50% of the revenue after the costs to issue tickets has to be returned to the state’s Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Fund.

While that funding has been finding a use at the statewide level, including in programs that help local cities apply for grants to improve their streets, that means less funding from cameras for direct infrastructure. Revenue from red light cameras, and school zone speed cameras, is able to stay at the local level, with many cities constructing guardrails around that funding to ensure it doesn’t simply bolster the general fund.

In Seattle, the debate around adding new cameras has centered around the fact that a majority of the city’s existing cameras are located in areas with more people of color than the citywide average — which are also, not incidentally, the areas with the highest levels of traffic fatalities. Cameras have financial impacts on drivers but also provide significant safety gains for other road users. In considering a deployment of additional school zone cameras over the next few years, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) proposes to add more cameras to schools in more affluent neighborhoods to balance things out, but it’s not clear that will have the maximum impact on safety.

Another guardrail the legislature added was requiring cities and counties to conduct an equity analysis before deploying cameras. “We’re looking at language to change that equity analysis requirement to make it more specific about what the goal of equity analysis is… to really focus their attention on: Who does it protect, and who’s likely to be cited,” McKechnie said.

With high speeds so prevalent across the state, the status quo is not tenable, but reversing the trend will clearly require a concerted effort at the local level everywhere — a heavy lift. To make the state’s roads safer, particularly for people walking and biking, there really isn’t another option.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.