Even in the automobile age, transit is popular, woven into America’s DNA, and primed for a comeback.

Like the beads in a kaleidoscope, popular myths about transportation in the United States have warped reality into a colorful illusion of logic for many otherwise intelligent people. The experience of growing up in car-oriented suburban societies has permitted anecdotal notions to masquerade as universal axioms: cars are always the best way to get anywhere, personal vehicles expand freedom while transit restricts it, and Americans love their automobiles as much as apple pie and baseball.

However, citing these unfounded assumptions illuminates nothing more than the antiquated mind palace of a bygone era — Japan, South Korea, Venezuela, and Mexico all have more baseball fans per-capita than the United States, and Americans love public transportation.

Out-of-touch motorists often whimsically declare that Americans do not favor transit expansions by waving around context-devoid statistics about how many Americans currently drive, treating present circumstances as wholly disconnected from past efforts to force motorization upon a nation sewn together by rail. Having been born into a trap doesn’t mean people desire to remain inside, as Americans in Seattle demonstrated by repeatedly approving transit measures, including when 81% of voters approved $39 million in annual transit funding in 2020.

Scrutinizing the country beyond Seattle, the Mineta Transportation Institute published a 2015 report compiling and analyzing polling data on transit opinions from across the United States. They uncovered massive popular endorsement of public transit expansion: more than half of Americans expressed support for increased government spending on public transit, and two-thirds (enough to amend the national constitution) said transit is of “medium or more importance.” The majority of Americans have expressed a desire to improve and expand their public transportation access: anyone claiming otherwise is speaking about an imaginary country.

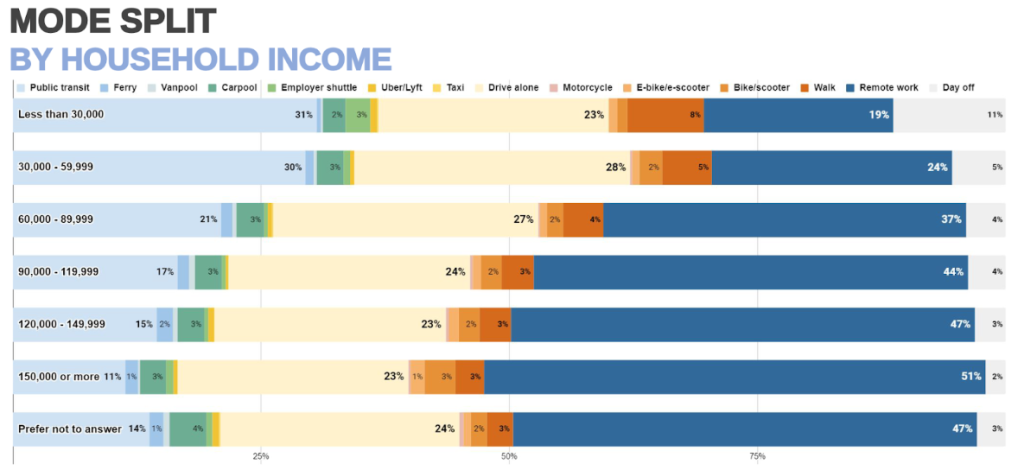

Returning to the famously car-flooded and drought-prone Pacific Coast, those in Washington State possessing the financial means to remain car-dependent still thirst for transit as California’s almond farmers pine for the Colorado. Data from the 2017 census showed transit was more popular among Seattleites earning more than $75,000 a year than those earning less, a notable social shift given the country’s history of classist narratives deriding transit users.

The will to use transit in Seattle is so strong that Link’s weekend ridership has been surpassing all-time highs even after the pandemic completely reversed Seattle’s commute patterns. Contrasting this with Metro bus ridership decreases — along with a 2023 poll from KOMO News indicating 84% of Seattle voters favor light rail expansion — and the view of American transportation demand in Seattle sharpens: people want frequent reliable rail transit which can accommodate flexible schedules.

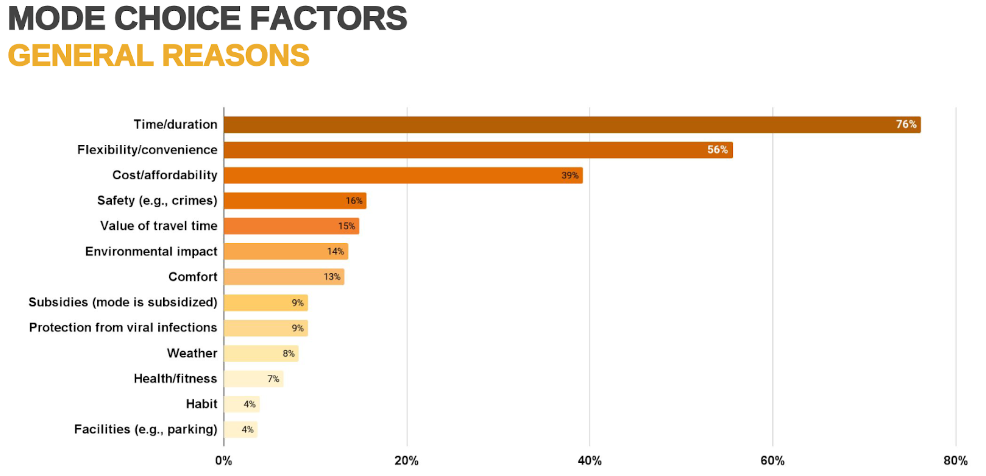

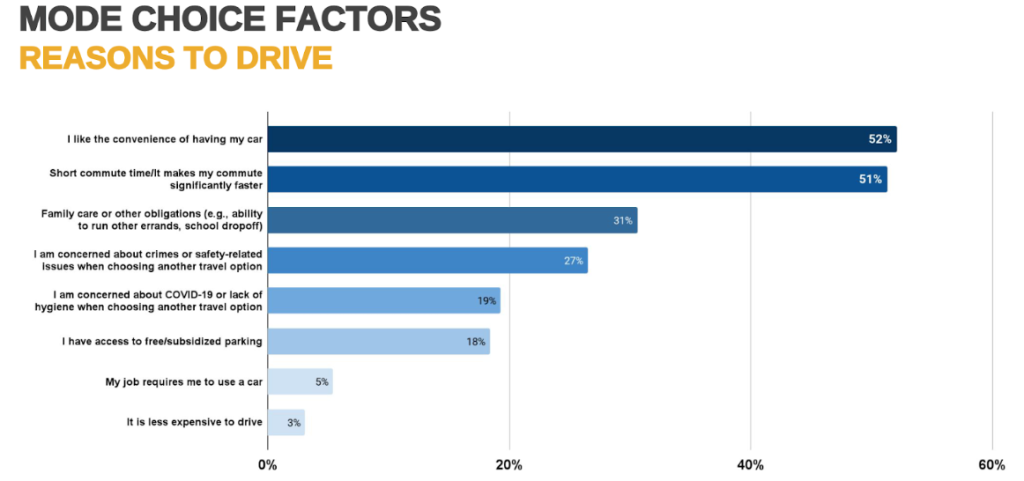

Survey data from Commute Seattle’s 2022 report makes this abundantly clear, as the three primary motivations for any mode choice are time, flexibility, and cost. When it comes to capturing mode share from drivers, providing speed and flexibility in scheduling will help address their main reason for getting behind the wheel: convenience. Only people who have never lived with reliable transit believe the myth that cars alone liberate movement; frequent, consistent, and reliable rail service liberates one from the confines of parking spaces, after all.

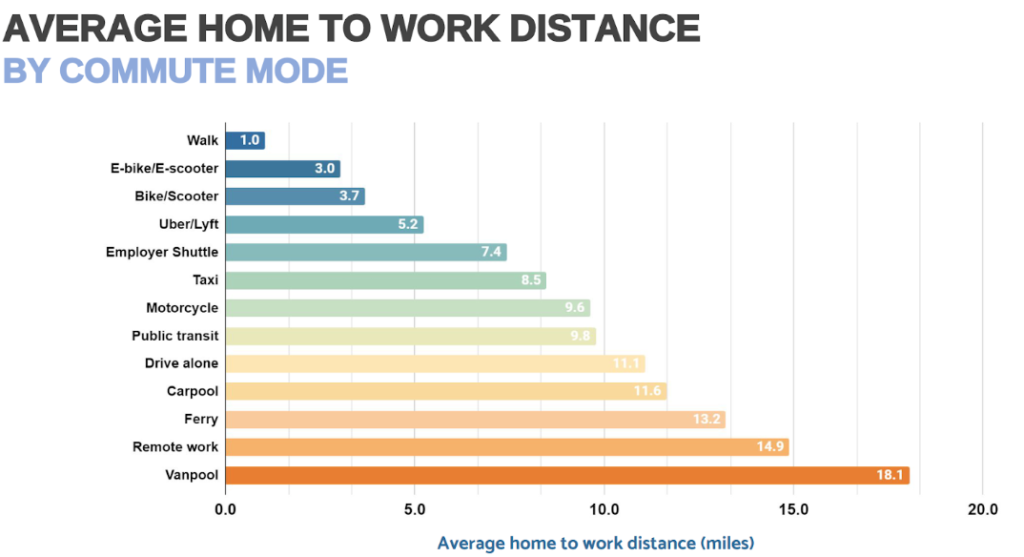

Cross referencing mode choice factors with data on home to work distance by mode reveals a picture containing a gap which longer more reliable rail services could fill: distances exceeding 10 miles. This gap has been closed before. Commute Seattle’s 2019 report measured an 18.1 mile distance for rail commuting, and the 2021 report shows rail distance falling behind driving for the first time. The statistical decrease in rail journey distance is likely attributable to Link’s ridership increases and Sounder’s plummeting numbers, further compounding the point that frequency and flexibility will be key in expanding rail’s ridership post-pandemic. Americans in Washington use rail if the schedules permit flexibility beyond 9-5 commuting.

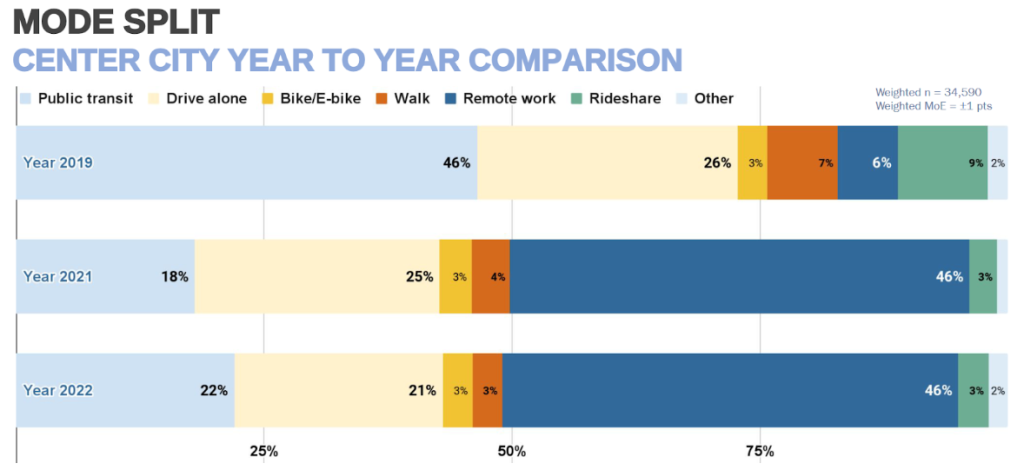

Even without improvements to Sounder’s schedule, commuters in Seattle are choosing transit over driving alone. Working remotely has remained stagnant at 46% after its astronomical increase from 2019 to 2021, but transit has increased from 18% to 22% since then while driving alone decreased from 25% to 21%. Recalling Link’s expansions over that time period, it appears that when Americans gain access to fast, frequent, and reliable rail service, they choose it over driving.

The data proves Americans choose rail over driving when they are given a reasonable choice, so why do myths about Americans’ preference for cars persist? There are many reasons — 70 years of federal and state emphasis on motorization, 70 years of foreign policy objectives focused on lowering oil prices, 70 years of automobile manufacturer lobbying and advertising, etcetera — but the most significant on an individual and cultural basis is classism, a social ill that has warped American policymaking from the country’s inception. Cars originated as a luxury vehicle for the elite, and the automobile remains a significant symbol of the conspicuous consumption which has historically reinforced class and aristocracy.

Meanwhile, public transit has historically served working class people, and Commute Seattle’s data shows this remains the case, in spite of the system’s newfound popularity with high earners. Policymakers are generally from the upper classes, which in combination with the neoliberalism of the Anglosphere inclines them towards sensibilities like those attributed to Margaret Thatcher: “Anybody seen in a bus over the age of 30 has been a failure in life.”

Allowances for democratic expression has permitted the people of the United States to elect transit-riding “failures” like Claudia Balducci to public office to counter this false narrative attacking more efficient modes of transportation, but the truth about common people’s preferences is waging an uphill battle against more than a thousand years of the hierarchical classism which has defined elite English-speaking social thought. This is why we continue to see hundreds of millions of dollars wasted on parking spaces and billions thoughtlessly sacrificed for highway expansions by a state ostensibly committed to increasing the fuel-efficiency and ecological sustainability of transportation. Educating out-of-touch leadership or replacing them with those who actually represent the people is how the mountains of unjust history are summited one step at a time.

Unlike narrow-minded classist policymakers, historically conscious Americans won’t find the popularity of rail surprising: inter-urban electric rail swept the nation long before the federal government prioritized car infrastructure, and inter-continental rail materially solidified the conquests of manifest destiny with golden spikes in the desert. While we can and should interrogate the morality of this colonial conquest, the fact remains: the United States, for better and worse, exists because of rail — the government solidified its hold over its present territory through rail expansion and its people continue to hold a keen cultural fascination with the locomotives which pulled them across time zones, biomes, and nations.

The history of American rail reflects the history of the country; our proudest achievements and greatest shames were all enabled by and connected to rail, from the genocide of Indigenous nations to the defeat of fascism. Today, rail gives us a chance to add a point of pride to our history: to fight climate change and increase equity. We should remember our honest and complex history and appreciate how it can impact the future by choosing leaders who represent the suppressed majority and the true spirit of its peoples.

Collin Reid

Collin Reid is an educator who moved to the Central District of Seattle in 2024 after having lived and worked in St. Petersburg Russia for eight years. His background in political science and international experiences led him towards urbanism and transportation as the foundational elements of society. He is a member of the Seattle Democratic Socialists of America.