The way cities conduct public outreach and local elections stacks the deck against homebuilding, research shows. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Seattle’s City Council has been pushing more public meetings for the Comprehensive Plan and rezone process — despite significant outreach that the City has already carried out. Research shows that public meetings systematically and structurally privileges wealthier, older homeowners, and even indicates that the public meeting process cannot be easily reformed.

This bias in meetings affects policy outcomes and decisions, which makes it harder to address Seattle’s housing crisis. It is an ongoing myth that the voices of typical public meetings accurately represent “the community.”

As part of Seattle’s one per decade Comprehensive Plan, Mayor Bruce Harrell ended up proposing 30 neighborhood centers, clusters newly zoned to support mid-rise multifamily housing amid existing commercial districts. Many of these new centers would include areas with existing single-family housing. Opponents have already attempted to reduce the number of neighborhood centers, as well as excluding single-family zones from the addition of new apartments.

The voices of these opponents are often heard through public meetings, when they assert that the community has not been “sufficiently consulted.” However, neighborhood groups tend to dominate town halls and other public meetings, and play a large role in setting a narrative of resistance to housing developments.

Meanwhile, builders contend the process needs to be faster, not delayed through unnecessary meetings overwhelmingly influenced by opponents. This is particularly true for smaller multiplex builders who don’t have the resources to wait out delays.

The public participation research

Critiques of public meeting processes do not just come from pro-housing advocates who are dissatisfied with the turnout. A number of key studies have shown that public meetings disproportionately represent older, wealthier homeowners, and show that the issue is a structural one.

For example, research from Katherine Levine Einstein, associate professor at the department of political science at Boston University and her collaborators found that “the people who show up to these [public] meetings are largely unrepresentative of their communities. They’re more privileged in a variety of dimensions,” said Levine Einstein. “They’re more likely to be homeowners, they’re more likely to be older, and they are also overwhelmingly opposed to the construction of new housing.”

The imbalance in whose voice is heard tends to be built into outreach processes.

“There are many barriers for public processes. Maybe the fact that most people don’t know that they’re happening, they don’t know the influence, they don’t know the impact,” said Eric M. Budd, a member of the executive team of Boulder Progressives, and co-founder of Bedrooms for People. “The reverse incentive for a homeowner blocking new housing is that they know exactly why they’re showing up, they believe that [the development] is bad for them, and they are going to protect their investments or their quality of life or whatever they have determined.”

Renters and lower-income people are also underrepresented due to barriers like work schedules, childcare, and simply lack of awareness. When lower-income people may need to work multiple jobs, or have long commutes, night shifts, or other challenging schedules, attending public meetings is not possible.

“Everywhere I go, I ask people what their commute is like,” said Anna Fahey, principal director of strategy at the Sightline Institute. “I try to figure out if people in my community can live close by. It’s quite surprising how many people, especially people working in retail or lower wage jobs, have to drive a long way to get their work. You can imagine that they don’t have time to show up at a hearing in the evening. And also, it illustrates how the people who would like to live in a place also don’t show up at the city meetings for that place, because they can’t afford to live there now.”

In contrast, for homeowners, who tend to be higher-income, many of these barriers do not exist, or can be more flexible. Many people who attend public meetings are retirees or empty nesters, who no longer need to structure their lives around work or childcare.

“Obviously, people who currently are living in a city have the ability to be present in these processes,” Budd added. “Whereas if you’re talking about building new housing, the people that will benefit from that new housing have not even been identified yet. They may not live in the city. They may not realize that this is housing that they are going to benefit from, so they are completely excluded from these processes. […] It’s completely one-sided.”

Importantly, research done by Sarah Schindler, professor of law at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, and Kellen Zale, associate professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center has found that partially because of legal notification requirements, renters are simply not notified of public meetings that concern them. On the other hand, homeowners are required to be notified, and receive a letter in the mail whenever developments in the neighborhood are going to occur.

This anti-tenancy doctrine is “a thread that runs throughout the law in all sorts of different areas, where tenants are treated as less than homeowners and as second-class citizens,” said Schindler. “This type of discrimination is really prevalent, not just in giving notice to tenants, but also in how tenants are treated more broadly by the law.”

The complex and multifaceted imbalance in the public meeting process is described as a structural problem by Levine Einstein. This means that the issue is created by broader land use institutions and factors that can’t easily be changed by amending the public meeting process.

“The reason for this [challenge] is because new housing has concentrated costs and diffuse benefits. If I live next door to a proposed housing development, it’s really annoying. You get the construction noise. You get the changes in parking, potentially depending on what they’re building. It changes your views,” said Levine Einstein. “All of those things are highly motivating to you as a likely opponent of the project to show up to a meeting. In contrast, you could be the most pro-housing person on Earth, and it is not a rational use of your time to show up to every meeting about a housing development.”

When public participation processes are designed this way, they simply entrench existing biases that give more power to homeowners and wealthy residents. Some researchers have suggested alternate routes to making these processes fairer and more in the interests of vulnerable residents. For example, this can include adding incentives, online meetings, holding meetings at different times, or sampling residents directly. However, if participation problems are indeed a structural issue, these types of approaches are unlikely to significantly improve the situation.

As it stands, public meeting processes continue to entrench historical discrimination, through the long history of exclusionary zoning and homeownership. Zoning code writers have historically prioritized single-family homes, and sought to discriminate against people of color, immigrants, and low-income people. As a result, homeownership became most achievable for White, wealthy families with generational wealth.

Ultimately, this confluence of factors means most public participation processes only give the appearance of democratizing decisions, allowing community participation, and being open to all. On the contrary, they reinforce already-existing structural discrimination.

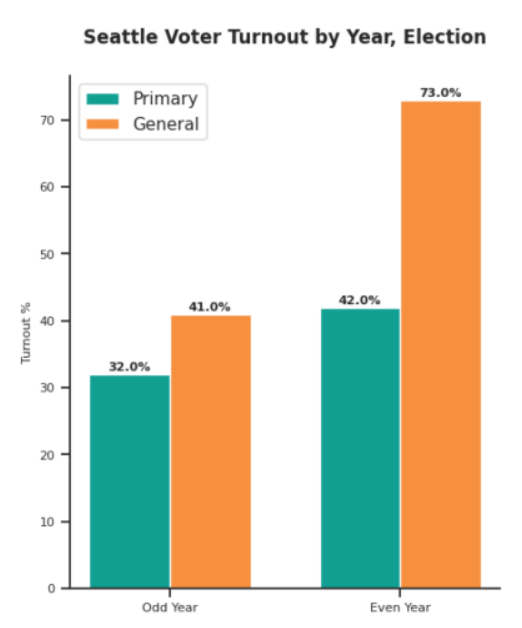

In addition, connections exist between public participation processes and local elections in terms of who participates. Particularly for off-cycle elections (which local elections usually are), the type of people who take part tend to be from the same demographic of public meeting participants: older, Whiter, richer, homeowners. “Essentially, there is a feedback loop between … who participates in public meetings, the public processes, the legislating, and who participates in [local] elections,” said Budd.

This means that large portions of city planning are driven by local officials elected through imbalanced, low-turnout voting, with public participation processes also heavily attended by housing opponents. This is in stark contrast to the state level and national level elections, which often elect pro-housing candidates, as well as wider opinion polling.

“We know from survey research, and from past public opinion research over many years,” Fahey said. “We just know that American voters are actually far more favorable to a bigger range of housing in their communities, than the handful of people who show up at a local hearing. We can show empirically that the people who show up do not represent the rest of the voting population.”

How this impacts Seattle’s housing policy

The consequence of over-reliance on public meetings is that Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan and rezoning process is being delayed — potentially to be shaped further by homeowner-led opposition. The development of new apartments and neighborhood centers gets delayed and perhaps watered down, with legal tactics playing a role, too.

For instance, residents in Madison Park, Hawthorne Hills, and Mount Baker have already put forward a legal appeal to request more environmental review beyond what the city has already completed. While on the surface it may appear that environmental review is a good thing, tactics like this are used to delay housing developments and maintain the status quo. The Seattle Hearing Examiner ultimately dismissed those appeals after two months of freezing progress on the plan.

For housing developments and the expansion of multi-family homes, mounting legal actions and appeals are a type of “predatory delay” approach. Predatory delay has historically been used as a term in situations where the fossil fuel industry has “stalled action on climate change for its own benefit.” When homeowners make use of legal mechanisms to draw out housing developments and prevent increases in density or changes to zoning, the primary benefit is to limit access to neighborhoods and maintain their own house prices and investments.

Some Seattle councilmembers have claimed to value outreach, without considering that the outreach they are asking for remains firmly in the camp of housing opponents. As Levine Einstein has noted, at a certain point it makes more sense (and is more equitable) for the city to ask for input early in a process to ensure that feedback from the community has been heard, and then to simply continue with the development in line with long-term city goals and the broader political consensus.

Searching for solutions

One big way cities have overcome these challenges is by making changes at the state or national level, to both give cities flexibility but also require certain changes to be made in housing development. For example, one option is “to have state-level policies that basically give cities the freedom to do some of the things that they want to do, even though they have all this local, vocal, opposition,” said Fahey.

“We worked on multiple state-level bills in Oregon, Washington, and Montana, where you, at the state level, legalize accessory-dwelling units,” Fahey added. “There is some question then about how cities actually implement this, and there’s a movement now about production accountability. Fourplexes are legalized, but you have to basically enforce that cities are making that happen.”

Making sure that accountability is tied to this freedom, e.g., of broadening zoning rules, is one step towards preventing process derailment through status-quo focused public opposition.

Another approach involves looking at potential reforms for public participation processes themselves. This includes weighted surveying, directly reaching out to renters and low-income communities, and improving incentives for attendance at public meetings. However, a number of these approaches will not actually change the problem, and miss the larger issue.

“We shouldn’t be soliciting public input every time we want to build a new unit of housing,” Levine Einstein said. “We shouldn’t be soliciting on a project-by-project basis public input, because that is never going to be representative of the broader community. It’s always going to be hard to make these meetings representative of the broader community, because getting a representative subset of people to show up to a three-hour meeting about zoning, is just not a reasonable expectation, given the average person’s interest in local politics. I think what we really need is to have more robust local democracies.”

Reducing public meeting processes would be a difficult task, however, both from a community perspective and from a legal one.

“There may be some over-participation going on,” Schindler said. “And maybe if we ratchet down the level of participation that would allow the decision-makers to make decisions free from so much homeowner influence.”

This type of approach however, can run into participation requirements that have become built into the legislation.

“There are procedural due process requirements, such as notice, and an opportunity to be heard is a requirement for certain types of actions, but not all of them,” Schindler said. “There definitely are ways that cities could decide to lessen participation. However, I do think there would probably be legal challenges to that, if they tried.”

Levine Einstein emphasized that one part of the solution is to create more accountability for public officials, but then let our public officials take charge of decisions about housing policy. The role of election processes should not be understated, despite often suffering from the same issues as public meetings. Many jurisdictions, Seattle included, hold local elections in odd-numbered years when voter turnout is much lower and the electorate overwhelmingly skews toward White, wealthy homeowners.

Shannon Grimes, a senior researcher at Sightline Institute, has analyzed voter turnout, and how to improve participation in local elections. She writes that “more voters participate when voting is easy: when they’re doing it anyway. It’s much easier to look up one more position and fill in one more bubble when you’re already completing a ballot than it is to open, research, and fill out an entirely new one at another time.”

Other research has found that “when cities switch to holding elections concurrently with presidential general elections turnout increases, the share of underrepresented groups increases, and the electorate is more likely to prioritize issues important to marginalized groups.” Changes to these processes can help get more pro-housing advocates elected in local elections, and allow the voices of lower-income residents and renters to be more present at all levels of governance.

Housing policy affects affordability, as well as urgent and pressing issues such as displacement and levels of homelessness in Seattle. As a result, comprehensive planning processes cannot be dominated by slow-moving, status-quo voices. While gaining input from the community is an important step in urban planning, research shows that public meeting processes are flawed, discriminatory, and often slow much-needed homebuilding down. When structural issues are pervasive and hard to fix, a complete rehaul and clear-eyed look at the planning process is sorely needed.

Leah Hudson is an editor and writer published by Insider, Atlas Obscura, and Penguin Random House New Zealand. Leah loves to write about sustainable urban development, mental health, and matters of the heart. She spends her time reading, walking her dog, and eating unreasonable amounts of chocolate. You can find her at https://leahhudsonleva.com/.