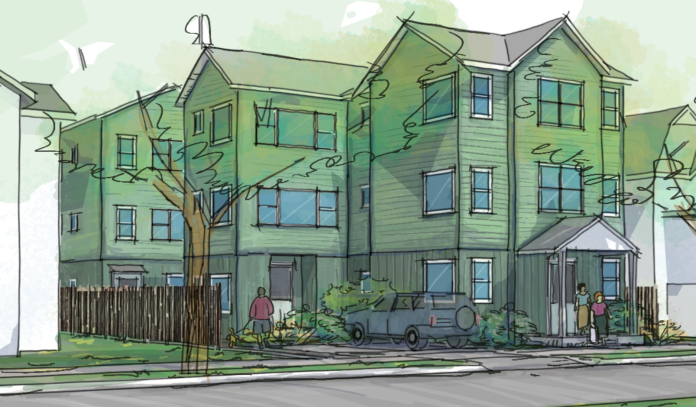

Ahead of a vote later this month to rezone Seattle’s residential neighborhoods to allow more types of housing, the city’s Planning Commission is broadly united in urging caution when it comes to some potential amendments that may be on deck at the city council.

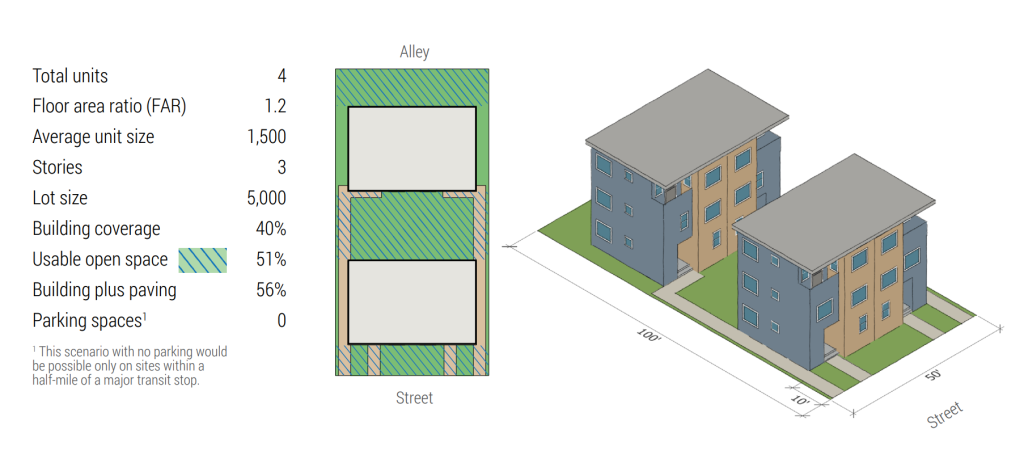

The zoning changes, which will allow property owners to build up to four units on all residential lots across the entire city and up to six units near light rail stations and RapidRide bus stops, are required by a 2023 state law, HB 1110. Facing a deadline to implement changes by the end of June, the Seattle City Council is set to adopt a temporary — or “interim” — ordinance that will remain in place for up to a year until permanent regulations can be adopted.

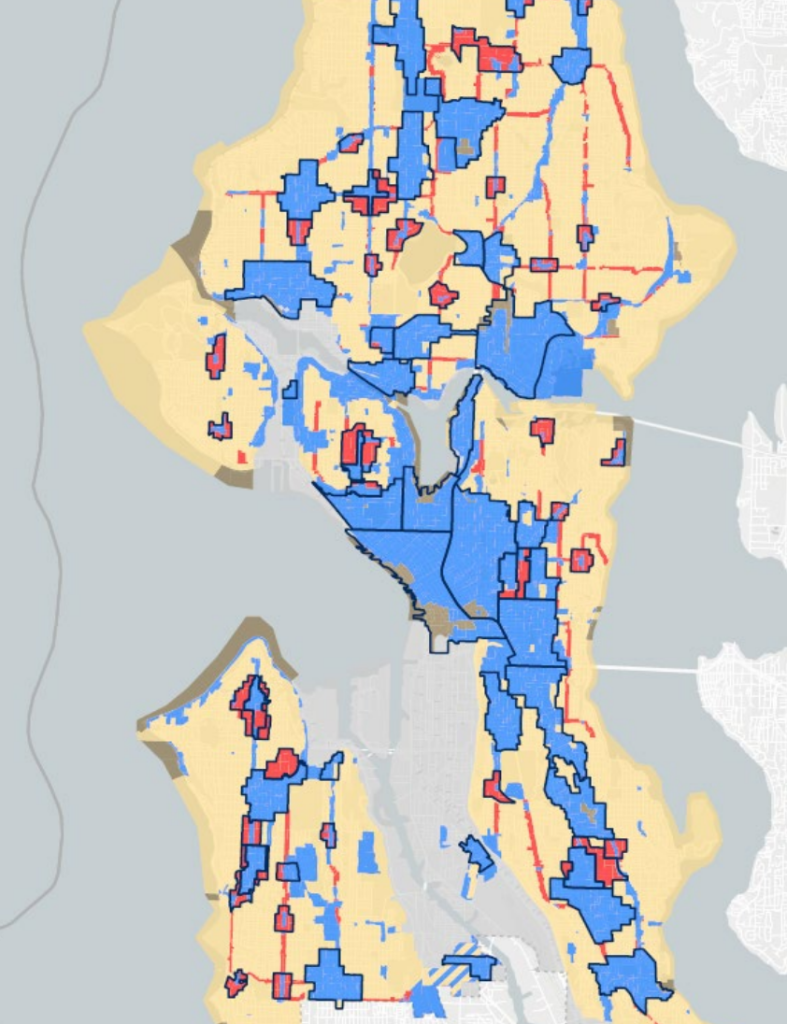

A plan to adopt permanent legislation to implement HB 1110 was thrown off course by a set of legal appeals against the city’s broader Comprehensive Plan. Even bigger zoning changes, including legalizing apartment buildings near frequent transit routes and in 30 new “neighborhood centers” around the city, have been officially pushed into 2026.

Amendments to the interim code haven’t officially dropped yet, and will be discussed at a committee meeting this Wednesday. But some ideas have already been floated by councilmembers, or presented as potential options by the city council’s independent central staff. At a meeting in late April, the Seattle Planning Commission discussed what those amendments might look like — and raised severe concerns about many of them.

For years, the commission has been a voice for going bolder when it comes to Seattle’s opportunity to make zoning changes, criticizing the status quo where most of the multifamily housing in the city gets sited in a relatively small number of areas. “Many renters, low-income households, and people with disabilities will still be unable to access housing in many of Seattle’s neighborhoods near amenities like parks, schools, and low-traffic, slower-speed tree-lined streets,” the commission wrote on an official comment letter on the draft Comprehensive Plan last December.

Now they’re raising the alarm about the negative impact proposed amendments could have on the ability for Seattle to add much-needed housing.

“The things that I’ve seen suggested — as in additional areas for tree protection, changes to the design review requirements, potential street improvements, and [Mandatory Housing Affordability], for that matter, are all potentially poison pills that are going to have the overall effect of dampening the implementation of middle housing throughout neighborhood residential zones,” Commissioner Matt Hutchins, an architect (an occasional contributor to The Urbanist), said.

“These are all things that are going to make a very difficult development market even more difficult. We’re going to see less housing come out of it,” Dylan Glosecki, another architect and urban designer, said. “The idea of a poison pill is what a lot of these will end up being.”

Mandatory Housing Affordability expansion

Housing advocates have long been bracing for a particular set of amendments, signaled by Councilmember Cathy Moore, dealing with the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program. Within the city’s urban villages — and the forthcoming neighborhood centers the council will be considering next year — developers are required to include a certain number of units that are made available for lower-income residents, or pay a fee that will subsidize the creation of those units elsewhere.

The Harrell Administration considered the idea of expanding that program to the entire city, but ultimately discarded that idea, publicly citing concerns about adding additional requirements onto smaller-scale developments. For months, Moore has criticized this decision, suggesting that if developers wanted to add units in the newly upzoned neighborhood residential zones, they should be required to also provide affordable housing.

“We’re going to open up the city to tremendous development and density, which is good, but we need to make sure that we’re utilizing all our tools, and MHA is a powerful tool,” Moore said at a meeting in March, at least the third time she brought up the idea this year alone. “It can be tweaked, but to simply say it shouldn’t apply across the board, I think, is a missed opportunity.”

Right now, an average MHA fee adds $28 per square foot to the cost of construction, a cost that can more easily be absorbed when a developer is moving forward with a large apartment building but which would likely become one more disincentive to adding additional units on the scale of middle housing. A study released earlier this year, completed by consultant ECOnorthwest, showed that middle housing would likely only be feasible on around 20% of lots within the city without adding MHA costs, due to a combination of current land costs and demand.

“What middle housing does is provide less expensive typologies of housing [the opportunity] to flourish,” Hutchins said at April’s Planning Commission meeting. “Those are townhouses, those are flats, those are backyard cottages. Those are things that aren’t as expensive as single family detached houses that are the dominant paradigm. What all these poison pills do is make all those things more expensive, and therefore reduce their benefit.”

If Moore is successful in adding MHA requirements to neighborhood residential zones, that move will set a strong precedent for the permanent code to be adopted later this year. But she’ll have opposition from at least one of her colleagues.

“I’m not supportive of expanding MHA to neighborhood residential zones because of the concerns of how it would make middle housing pencil,” Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck told The Urbanist. “We are in a housing crisis, and things are not getting much better right now, I’m deeply concerned about the impact of everything related to this trade war and the materials to construct said housing.”

Street improvements

Another potential tweak that could be on deck relates to adjacent street upgrade requirements. With around one in four city blocks in Seattle missing sidewalks, filling in the gaps in pedestrian infrastructure and basic accessibility is undoubtedly a change that needs to occur as the city continues to get denser. But planning commissioners raised concerns about asking developers to pick up the tab for those upgrades.

Currently, developers building in the city’s neighborhood residential zones are only required to build sidewalks, curbs, and curb ramps if a project includes ten or more units, or if the project would create at least 10 new lots. But the council could change that requirement, adding on a stipulation that middle housing types like four- and sixplexes also need to come with this infrastructure. If they do, that could ultimately create an incentive back toward single-family homes, which would likely be able to include detached and attached accessory dwelling units (ADUs) without triggering any adjacent upgrades.

“I really, really, really do want to see more street improvements happen, but it just kind of feels like another kind of way to disincentivize the redevelopment in our neighborhood residential zones, and not actually an intention to create sidewalks, because what it will do is yield no development and no street improvements, instead of the actual intent,” commissioner McCaela Daffern, who works in affordable housing policy at King County, said.

Commissioner Cecelia Black, one of the city’s biggest advocates for new sidewalks in her day job as a community organizer with Disability Rights Washington, was also in agreement that it shouldn’t be on the housing developer to add those sidewalks. “There’s just so much better ways to build sidewalks than taxing new developments,” Black said.

With Seattle’s housing market already facing significant headwinds, all eyes are on potential council amendments this week. Major changes could put a significant damper on updates that are only expected to have a modest impact on the city’s housing supply as it is.

This Wednesday’s Select Committee on the Comprehensive Plan meeting will focus entirely on those amendments, with public comment accepted both virtually and in-person starting at 2pm. On Monday May 19, the council will hold a public hearing to solicit broader comments on the overall proposal, starting at 9:30am for speakers who are calling in by phone and at 4pm for in-person commenters.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.