The stacked flat, a small multifamily building with six to 20 apartments, is an essential housing type that dots our residential streets from Columbia City to Phinney Ridge and beyond. At the turn of the century, Seattle needed housing for its rapidly growing population. Stacked flats offered quick solutions to house more people on less land. So, what happened to them?

The term “missing middle” is a label describing the lack of new housing being built between detached houses and five story apartment blocks. Once the mainstay of new housing, these smaller multifamily buildings have been legislated out of existence due to zoning restrictions, building regulations and financing practices.

Instead of growing housing within, Seattle pushed new homes out to surrounding suburban sprawl while downzoning our city and mandating single-family homes as the only construction option for 85% of our neighborhood land over the next 75 years. For the rest of the city, stacked flats were legal, but didn’t make sense with Seattle’s Urban Centers & Urban Villages planning concept, where housing supply was delivered in larger quantities by large apartment buildings through lot assembly.

Despite “missing” from modern planning, these beloved stacked flats hide in plain sight as fugitives of modern codes. They are part of the fabric of every Seattle neighborhood. They offer housing on a single level and with windows on two or three sides, good for people who want daylight, natural ventilation, prefer more space and don’t want to navigate a stair as often as townhomes require. Luckily, recent state laws have legalized them beyond slivers of “low-rise” zoned land, allowing them broadly citywide once again.

House Bill 1110, passed in 2023, re-legalized these four-, five- and six-unit projects statewide in all areas zoned for single family detached residential homes. Progressive leaders recognized that it was a mistake to prohibit these missing middle housing options and saw them as a solution for adding housing supply, a crucial part of affordability.

Legalization was the first step, but stacked flats still face numerous hurdles that prevent them from being built. These are hurdles that add enormous amounts of cost and complexity to this solution, resulting in this “legalized” housing model still missing from new supply.

Five key hurdles remain that must be overcome in order to make stacked flats viable:

State Level Hurdles:

1. Falling under Commercial Building Code vs Residential Building Code

2. Falling under Commercial Energy Code vs Residential Energy Code

3. Condominium definitions and liability risk

City Level Hurdles:

4. Seattle’s stacked flat bonus falls flat

5. Piled on infrastructure costs, affordability taxes, and permitting barriers

State codes stand in the way

1. Commercial Building Code vs Residential Building Code

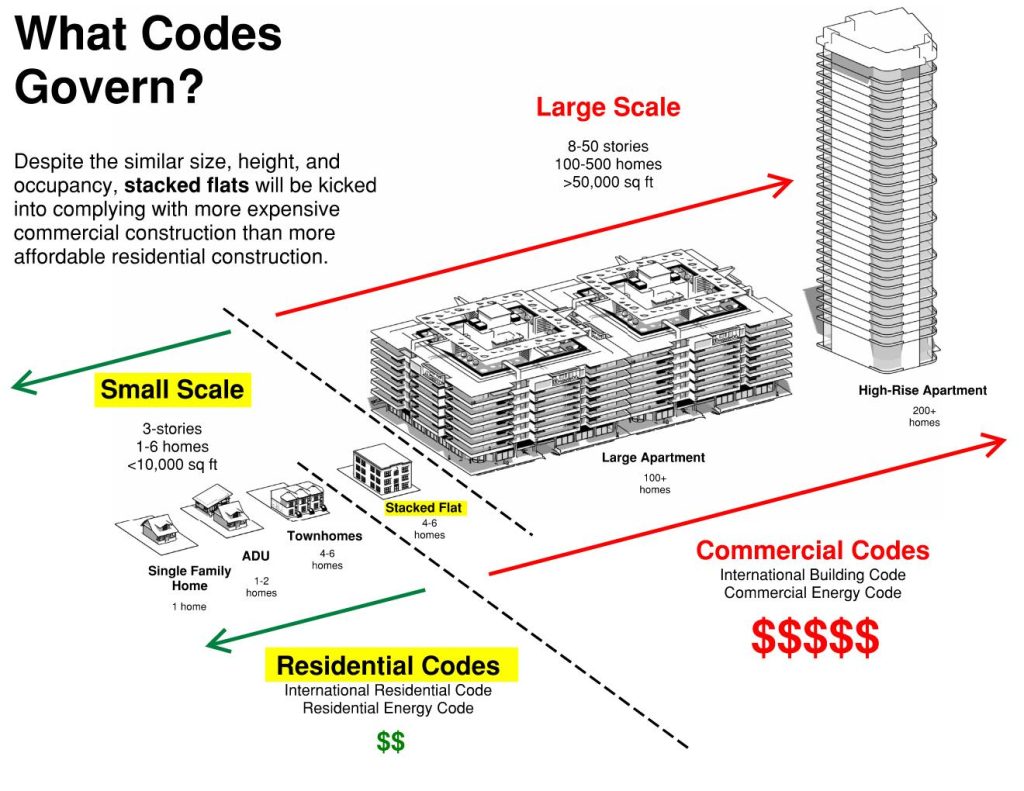

Residential buildings are currently governed by one of two codes. One is the International Residential Code (IRC)—typically reserved for single family housing, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), duplexes, and townhomes, and the other is the International Building Code (IBC)—reserved for everything else, typically for much larger buildings. The IBC requires expensive building upgrades that the IRC does not require. Unfortunately for stacked flats, they fall into the IBC, saddling a small six-unit building with many of the features and costs of a 400-unit full-block apartment building.

When built as three-story townhomes, these homes fall under the IRC, saving a lot of money, which is why you will see six townhomes built before you see six stacked with the same building area. To get ahead of this, Washington passed House Bill 2071 into law last year requiring missing middle housing to use the IRC.

However, the devil is in the details. Currently, the State Building Code Council (SBCC) is considering how to amend the state’s IRC to accommodate stacked flats. Amendments are proposed through the Technical Advisory Group. House Bill 2071 created this subcommittee, at the request of AIA Seattle’s Housing Task Force, with the specific intent of lowering costs for missing middle housing. This Technical Advisory Group has two proposed amendments to consider.

One proposed amendment is from the Washington Building Officials (WABO) — a professional organization of code reviewers and building inspectors across the state — requesting the IRC to reference sections of the IBC for missing middle housing. The proposal was submitted by a building official in Seattle. WABO’s proposal circumvents state law and would add over-engineered solutions and added costs killing these projects across the state.

If the SBCC accepts WABO’s amendment, new flats will have to comply with the IBC and provide robust fire sprinkler systems, more complex wall assemblies, expensive fire alarm systems, water pressure booster pumps, and other utility upgrades. IBC requires more detailed mechanical and plumbing reviews which translate to longer permitting review times and higher soft costs. None of these items are required in single-family homes or townhomes because the IRC recognizes that small-scale buildings with relatively few occupants are inherently less hazardous.

By imposing these IBC regulations on stacked flats, the cost per unit exceeds that of a townhouse, making stacked flats more expensive to build despite providing the same number of homes, occupants and built area. Very few developers will accept the additional cost, complexity and risk of stacked flats, when they could build townhomes under IRC instead.

The other proposed amendment is from housing advocate and planner Markus Johnson, which would keep these buildings entirely in the IRC without IBC code references. The amendment would treat a six-unit stacked flat similar to a six-pack of townhomes, recognizing the stacked flat is no different in size, scale and occupancy of six townhomes. This gives stacked flats the same chance at being built economically as townhomes and gives the developer a choice. Markus’s amendment would align with state law in lieu of the WABO proposal which circumvents the law by adding IBC code references into the IRC’s appendix.

You are encouraged to email the SBCC (sbcc@des.wa.gov) and tell them to reject the WABO amendments and support Markus Johnson’s amendments citing the desires of the state law and ability to lower the cost of housing.

2. Commercial Energy Code vs Residential Energy Code

Right now, the energy code defines what is residential and what is commercial based on where the residential entrances open. If they open to the exterior, it’s under the residential code, if they open to the interior (like a stair or corridor) it falls under the commercial code. This again is why townhomes fall under the residential code and these stacked flats would fall under the commercial code which is just adding complexity and builders’ unfamiliarity with construction practices.

Perhaps the black and white code definitions don’t fit this gray area? To avoid unforeseen costs we should revise the rules giving builders the choice of using the Residential or Commercial Energy code for stacked flats.

Last month, an energy consultant proposed this very amendment (Proposal 24-GP1-88R), citing the same logical discussion points brought up here, and the Technical Advisory Group narrowly voted it down. This is an ongoing process and a revision to the definition has also been proposed in the Residential Energy Code advisory group.

If you are interested in joining either the SBCC Commercial Energy Code Technical Advisory Group or Residential Energy Code Technical Advisory Group as a volunteer to promote missing middle housing and make these types of decisions, please email Tammie Sueirro at AIA Washington (tsueirro@aiawa.org) and see more information at the end of this article.

3. Condo Definitions and Liability Reform

Condo liability reforms have made their way through the state with House Bill 1403 signed by Governor Bob Ferguson on Wednesday, but those reforms are reserved for condos that are two-stories of housing or less. Three-story buildings would only qualify if one level is reserved for parking. A three-story sixplex with housing on all three levels would not fall under the exemption and poses yet another hurdle preventing banks from being comfortable financing this investment.

Simply put, if the same number of units and area can be achieved as townhomes with far less risk, why would a developer opt to build a condo building when they can just deliver townhomes and avoid this liability? We must reform this definition in order to give stacked flats the same chance of development as townhomes.

The City can do more.

4. Stacked Flat Bonus falls flat

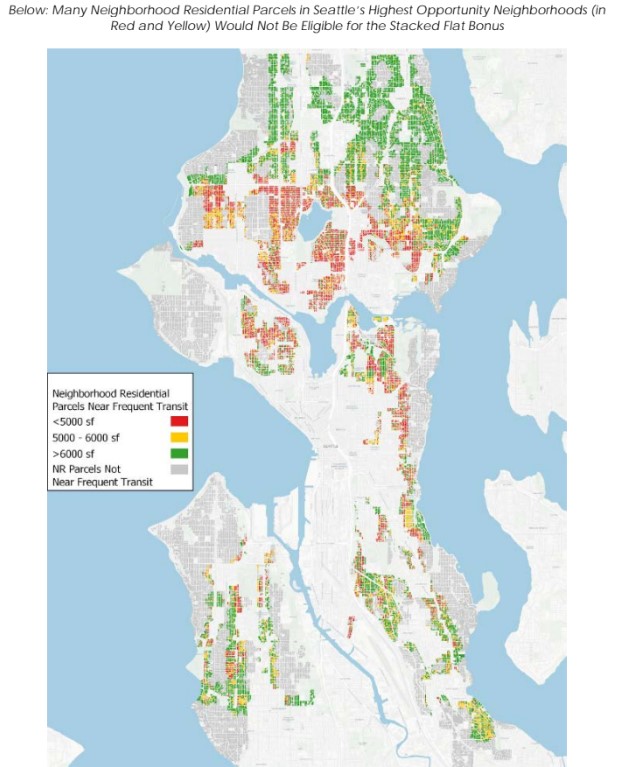

Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) is tasked with legalizing four and six units per parcel citywide as part of the One Seattle Plan. To encourage stacked flats, OPCD enlisted a bonus offering any lot with a minimum size of 6,000 square feet to increase their buildable area from 7,200 square feet to 8,400 square feet. The problem, however, is that this bonus doesn’t apply to enough lots or go far enough.

Seattle’s OPCD hired EcoNorthwest, an economic consulting firm, to study their solution and evaluate the financial feasibility of their plan. Long story short, the proposal fell flat. EcoNorthwest predicts virtually zero stacked flats being built in the next 20 years. The reasons outlined in their report include building code restrictions, condo liability, financing concerns, city-mandated infrastructure costs, and a lack of added incentive.

The report recognized that very few lots south of 85th Street meet the minimum lot standards for the stacked flat bonus, banning the pursuit before it can even be tried for almost half of the city in our most transit-rich and walkable neighborhoods. With proposed solutions to state hurdles and relaxing financing concerns, now we just need the City of Seattle to step up and offer better solutions.

Washington State’s model code ordinance does not require lot minimum sizes for a six-unit stacked flat and allows more building area than Seattle’s proposal for a six-unit stacked flat with the bonus. As a solution, Seattle should remove the lot minimum and double the building area bonus for any project pursuing a stacked flat to match the model ordinance’s floor area ratio (FAR) of 1.6 (or greater) for a six-unit building. This adds more incentive to pursue the effort and opens up more lots and neighborhoods across the city for adding this housing option.

5. Piled on infrastructure fees, affordable housing fees, and permitting reform

Currently, utility upgrades are levied against the first developer that approaches the block in need of upgrade, putting all the financial obligation and construction timeline on their project simply for going first. Mayor Bruce Harrell has wisely proposed a cost-sharing initiative intended to remove this barrier and encourage housing growth. We need more attitudes like this when it comes to infill housing solutions.

Seattle must maintain that these projects are exempt from Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA). Despite the position of the Seattle Planning Commission to maintain this exemption, Council is considering MHA fees on new missing middle housing. MHA fees are a burden to smaller projects and have shown us after a six-year experiment that it is mostly funded by a few large projects while cratering the townhome market in favor of single-family home and ADU construction to avoid the obligation or fee.

Despite not requiring Design Review for this zone, Council is considering adding this additional process for missing middle housing. Design Review is a hurdle that brings schedule uncertainty, added carrying cost at higher interest rates, frivolous design changes and requires an additional land use permit known as a Master Use Permit (MUP) which have historically added 400-900 days on average to the overall permit process. Design review has been suspended temporarily for all large-scale downtown and South Lake Union housing projects and single-family homes have never required to go through the program at all. Missing middle housing should be afforded an exemption and avoid this frivolous permit process and save on time, money and risk.

With current city council discussions occurring for MHA fees and Design Review being applied to missing middle housing, we encourage you to email your councilmembers recommending they do not impose the fee, require performance on site nor go through Design Review.

What kind of city and state do we want to be?

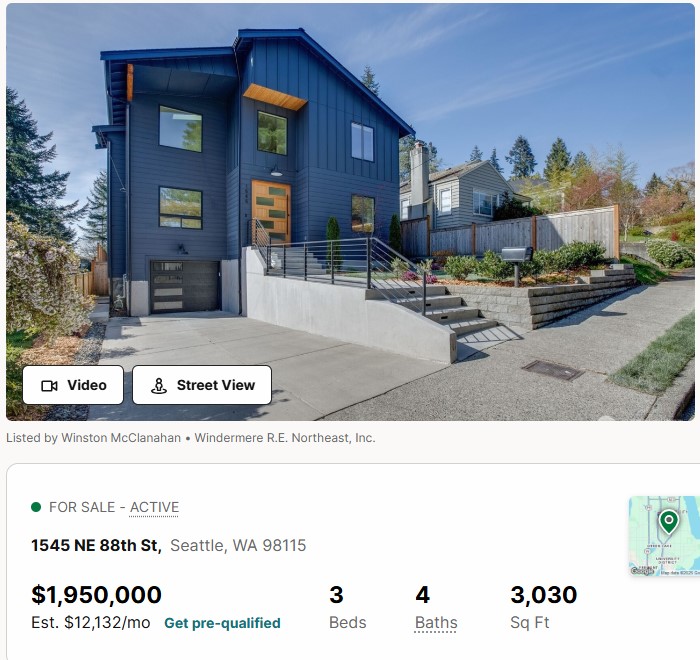

All of this to say, these reforms will not make any building more dangerous, it will not make them unlivable or ugly, it will just make them less expensive and easier to build. A single-family home today does not go into the commercial building code, or the commercial energy code, it does not have condo liability laws, it doesn’t have to pay MHA fees, it doesn’t have to pay for street improvements or most utility upgrades, it doesn’t need to get approval at design review, and it doesn’t face the same restrictions and hurdles anything slightly larger does. What does that say about who we are and what we want built when we incentivize behemoth mansions at the most unaffordable price range housing has to offer?

If the solution we want is a less affordable city, one with expensive new single-family homes, narrow and vertical townhomes, large apartment buildings of small units, and nothing in between, then we currently have the state codes and city zoning plan to deliver that vision. There is nothing wrong with owning a single family home, townhome or ADU and there isn’t anything wrong with living in a studio apartment in a large building, but if we want more housing options that include stacked flats, and we want to be a more affordable city for families, retirees, people with limited mobility, and people with children, then we clearly need to do something different or stacked flats will go missing forever.

Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck asked city planners what they can do to incentivize stacked flats based on the dire projection in the feasibility report, and the planners couldn’t give an answer. Instead, they threw up their hands and said the deck is just stacked against their proposal. When your job is finding housing solutions for the city, this is not a good enough answer.

When the deck is stacked against you, innovators don’t give up, they find success by identifying the challenges, proposing solutions, and they take action. Innovation is in the DNA of Seattle and this state as a whole, isn’t it? Are we still a city and state of innovators?

Because if we are, then it’s time to bet the farm on these solutions and take down the house.

*

This article is the result of input from passionate architects, planners and code committee members involved in the effort to increase the supply, variety, and affordability of housing in our city, region and state. We want to thank the hard work and dedication of the AIA Seattle and AIA Washington for all the foundational work done for missing middle housing reform.

Please encourage the state officials at the SBCC to support Markus Johnson’s amendment and reject WABO’s amendment, support flexibility in energy codes by changing definitions to include all housing types included in HB 1110. You can contact them at (sbcc@des.wa.gov).

Contact your state legislator and sponsors of HB 1403 to support condo liability reform for three story missing middle housing.

Please contact your city councilmembers about making stacked flats more viable in the One Seattle Plan by removing lot minimum requirements, doubling the bonus, maintaining MHA and Design Review exemptions, and removing costly street and utility permits.

If you are interested in joining the SBCC on their Single Exit / Multiplex Technical Advisory Group (TAG) team to help make stacked flats possible, there are positions open and available (Page 4) to be filled for Building Owner / Property Manager, Structural Engineer, Fire Systems Engineer, Manufacturer / Supplier, and Insurance / Appraiser. All you need to apply is a letter expressing interest emailed to (SBCC email) and you can make a difference on a state level. If you have questions about serving on the TAG, you can email Tammie Sueirro at AIA Washington (tsueirro@aiawa.org).

Bradley Khouri and David Neiman also contributued to this article.

Khouri is the founder of b9 architects focusing on infill urban housing in Seattle and is an Affiliate Assistant Professor at the University of Washington. He has served as the President of the AIA Seattle Board of Directors and Chair, including many AIA Seattle Task Forces.

Neiman is a partner at Neiman Taber Architects, an award-winning Seattle firm specializing in urban housing with a focus on issues of livability, affordability, community, and access to housing for all. He is a past member of the Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) Committee and NW Design Review Board chair.