By allowing taller buildings, smaller elevators, more efficient stair configurations, cities can broaden housing options and boost homebuilding.

In 1973, Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman tasked the Building Code Advisory Board with examining how the city’s building code could be modified to “encourage in-city living, redevelopment, and new construction.” Focused on reversing the city’s population decline and making city living more desirable, the Building Code Advisory Board’s recommendations were adopted into the 1977 Seattle building code and allowed apartment buildings taller than three stories to be served by a single staircase.

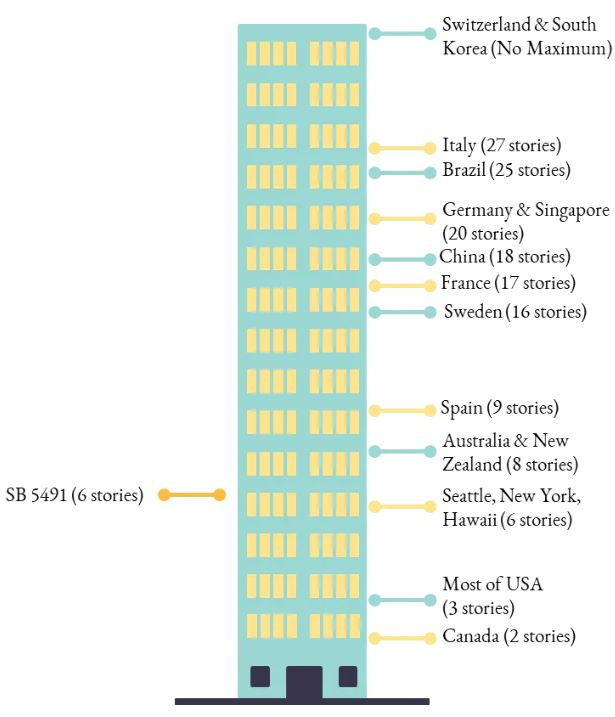

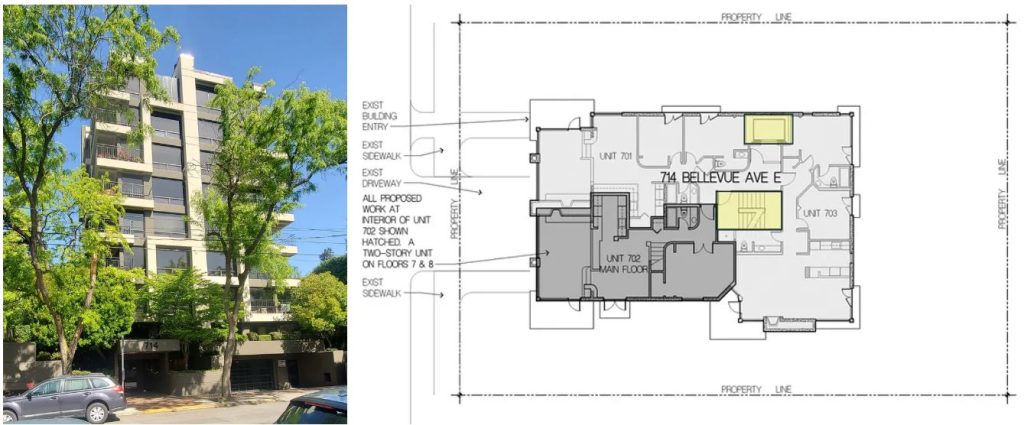

It didn’t take long for the code amendments to deliver results, as in 1978, the Pike and Virginia Building overlooking Pike Place Market became Seattle’s first taller single-stair multifamily building. Seattle’s single-stair code evolved over the decades, solidifying at a six-story maximum that almost 50 years later has become the reference point for statewide changes (2023’s SB 5491) and housing advocacy in other cities, states, and provinces across North America.

In 2009, a Seattle Planning Commission study on potential zoning changes to the city’s highrise (HR) zone started to highlight some of the building code restrictions that make Seattle highrises large, expensive, and challenging to build outside of Downtown and U District. Noted in the study was the finding that Vancouver B.C.’s and greater British Columbia’s ability to build more desirable highrise multifamily buildings for a reasonable construction cost is heavily influenced by their building code’s allowance for scissor-stair configurations and that without significant changes to Seattle’s codes we will not see similarly affordable to build highrise housing.

Lastly, in 2018, Seattle amended the building code to allow six floors of wood construction over a two-story concrete base. This change happened because architects and developers alerted city officials that they would be unable to fully maximize the new 85-foot multifamily zones that came out of the 2015 Comprehensive Plan and the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) updates.

This brief history lesson leads to the now, where the city once again has an opportunity to improve building codes for better multifamily housing. Building on the growing body of research related to housing supply barriers caused by building codes and referencing housing goals and policies in the One Seattle draft plan, I have identified a series of building code changes that would provide desirable and more accessible multifamily housing at a more reasonable construction cost than most current multifamily development in Seattle.

Although they may be busy, city officials should be familiar with the identified code amendments and the housing options they can provide because the Seattle 2024 building code update cycle is starting in 2025 (yes, this is behind as well, but it is not the city’s or the state’s fault on this issue). Whereas, the most significant zoning changes in the One Seattle Comprehensive Plan — the zoning changes to neighborhood centers, transit corridors, urban centers, and regional centers — are set to occur between 2026 and 2028.

Given that the 2024 building code update likely won’t happen until late 2026 and the following 2027 building code cycle won’t conclude until late 2028/early 2029. Not taking advantage of the current opportunity to improve Seattle’s building codes could hinder the phase 2 and 3 zoning code updates ability to maximize new housing development and achieve housing goals or lead to a similar situation that happened during the last Comprehensive Plan update where zoning updates are misaligned with the building code.

Therefore, the city should plan ahead and consider adopting the series of building code changes proposed in the research report I published earlier this year. The report covers in more detail the actual suggested code language changes and which changes support goals and policies in the draft One Seattle plan. The proposed code changes can be summarized as:

Taller Single-stair Buildings:

- At minimum, increase the allowed number of stories for single-stair buildings from six to eight stories.

- Remove the current limit of two single-stair buildings allowed to be built on a lot. Let lot constraints, zoning code, and design decisions dictate how many fit on a lot.

- Allow up to 15-story tall single-stair buildings under higher safety parameters such as being constructed with at least three-hour rated fire resistance material.

Scissor Stairs:

- Allow scissor stairs for residential buildings.

- Allow scissor stairs for small commercial and office buildings that are six stories or less.

Right-sizing Elevators:

- Adopt ISO 8100 as an equal elevator safety code option for elevator and conveyance compliance.

- Lower the minimum elevator car size for buildings that don’t require an elevator to 43 inches by 55 inches (1092 mm by 1397 mm).

- Lower the minimum elevator car size for required wheelchair full turn radius accessible elevators to 52 inches by 63 inches (1321 mm by 1600 mm).

- Lower the minimum elevator car size for ambulance accommodated and wheelchair full turn radius accessible elevators to 52 inches by 84 inches (1321 mm by 2134 mm).

- Lower the minimum elevator car size for ambulance stretcher accommodated elevators to 43 inches by 84 inches (1092 mm by 2134 mm).

Taller Single-stair Buildings

Single-stair buildings or point access block buildings are buildings that are designed with a single staircase and often with a single elevator core. Single-stair buildings are a common design of multifamily housing in most other high-income countries across the world. Many such countries allow single-stair buildings taller than the six stories allowed in Seattle. The benefits single-stair buildings bring to the people living in them and the overall housing market include:

- A greater diversity in unit sizes, which can support a greater number of family-sized units

- Homes that can cross-ventilate by having open windows on at least two sides of the unit

- Sun and light on multiple sides of the unit

- Increases small lot development and reduces need for costly lot assembly

- Increased building compactness or thinner buildings that are less “imposing” and leave more open space for residents

The recommended changes would allow single-stair buildings to be a viable development option in the city’s midrise zones, which draft documents suggest could be a more prominent zone in the city. For example, eight-story midrise buildings in Seattle typically have two stories of concrete and six stories of wood on top due to the 2018 building code amendments. Seattle also allows mass timber construction level C (Construction Type IV C), a max height of 85 feet, and eight stories for residential development.

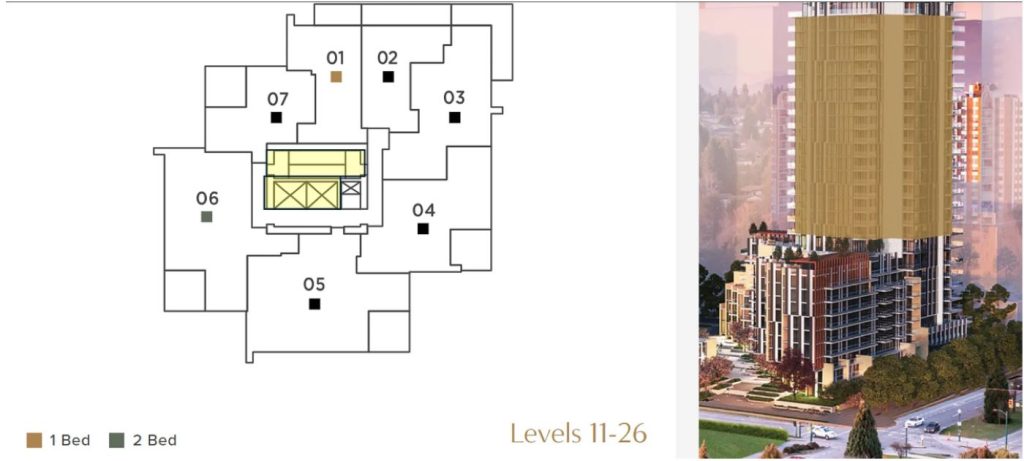

Raising the max height of a single-stair building to eight stories aligns with several building construction type methods that allow builders the option to maximize allowed heights in a cost-effective manner. Similarly, raising the single-stair height allowance to 15 stories would align with mass timber level B (Construction Type IV B) or concrete construction. Therefore, allowing phase 3 of the One Seattle Plan to consider zoning changes that would enable 12–15-story apartment buildings in urban and regional centers in areas near light rail stations. Such areas may not be feasible for the large 10,000+ square foot building footprint highrises in Downtown or U District but are very likely to be feasible for the 2,000–4,000 square foot building footprint highrise that would be allowed under the building code changes.

Also, other countries that allow taller single-stair buildings do not limit the number allowed per lot. By limiting the number of single-stair buildings on a lot, one essentially guarantees that development on large sites such as old parking lots or old transit construction parcels near light rail stations will be larger bulky buildings that always have a larger percentage of studios and one-bedrooms and large, expensive commercial spaces.

Scissor Stairs

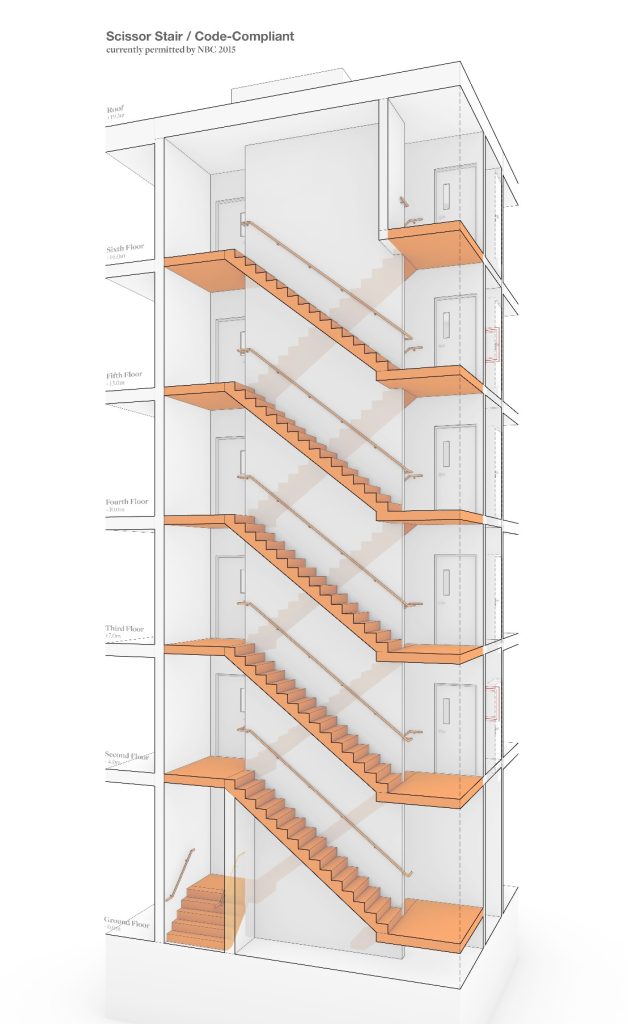

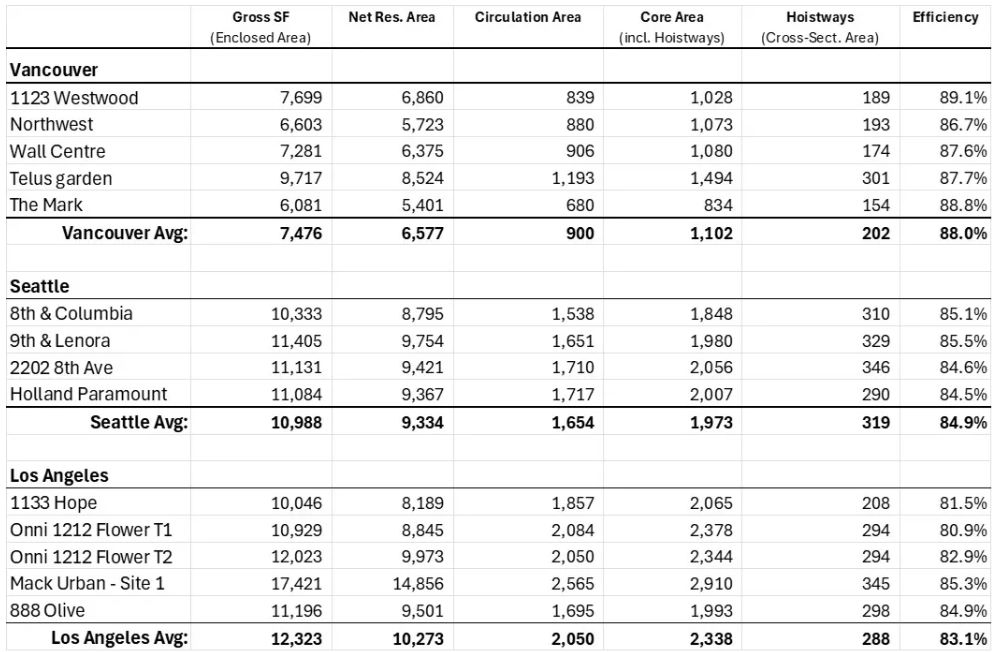

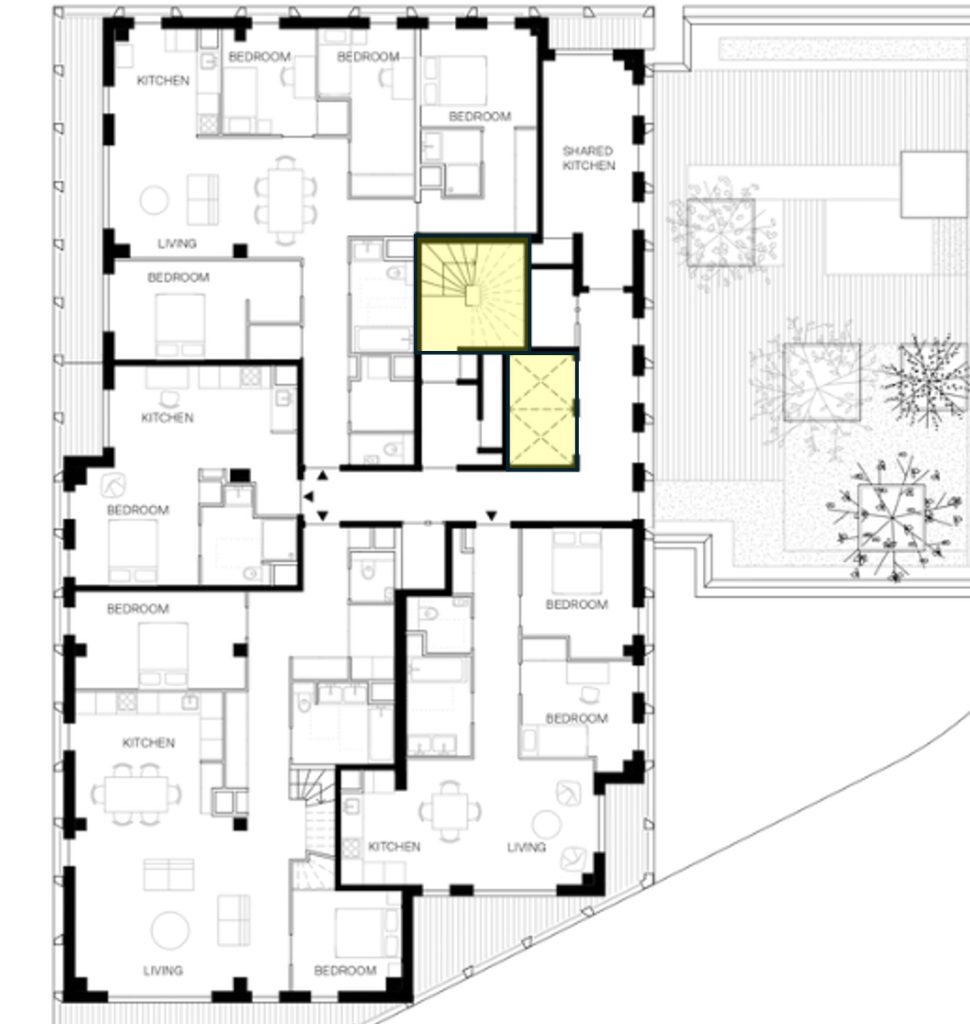

Scissor-stairs are a two-stairway configuration that includes two interlocking stairways that provide two separate exits located within one enclosed fire-protected stairwell. The stairways in a scissor-stair configuration never cross or intermingle with one another because there is a fire-rated wall separating the stairways. The highrise condo and apartment buildings popular in Vancouver, British Columbia’s (B.C.) downtown, and broader B.C.’s Transit Oriented Development and city centers are often designed with scissor stairs.

Scissor stairs allow for less space dedicated to stairs, hallways, and elevators in a building and more space for living space. This allows for the entire building to be skinnier or more compact than the buildings we typically build in Seattle, which saves on the amount of land needed to construct the building and the overall construction cost because one is constructing a smaller building.

For comparison, building footprints of residential highrises in Vancouver generally range between 6,000 and 7,000 square feet. Whereas in Seattle, residential highrise development typically has building footprints between 10,000 and 11,000 square feet. Even when trying to compare a similar-sized development in Vancouver (i.e., Telus garden) to a Seattle development (i.e., 8th & Columbia), the Vancouver development with scissor-stairs has 2.5% or 225 to 275 square feet more leasable building area per floor than the Seattle development with spatially remote stairwells. That may not seem like much of a difference, but 70 to 100 square feet can mean an additional bedroom or private outdoor deck space for several units per floor.

As part of Phase 3 of the One Seattle Plan, Seattle will likely consider allowing more residential highrises in regional centers and near new light rail stations to achieve housing, transportation, and climate goals. In Vancouver and other cities worldwide, residential highrises are a great housing form for dense housing that supports family-sized units near transit and other desirable locations. Having codes that allow for such structures to be compact and thin makes them more feasible while also increasing the separation between adjacent structures, which provides better views, enhances interior lighting, and provides for more ground-level open space.

Right-sizing Elevators

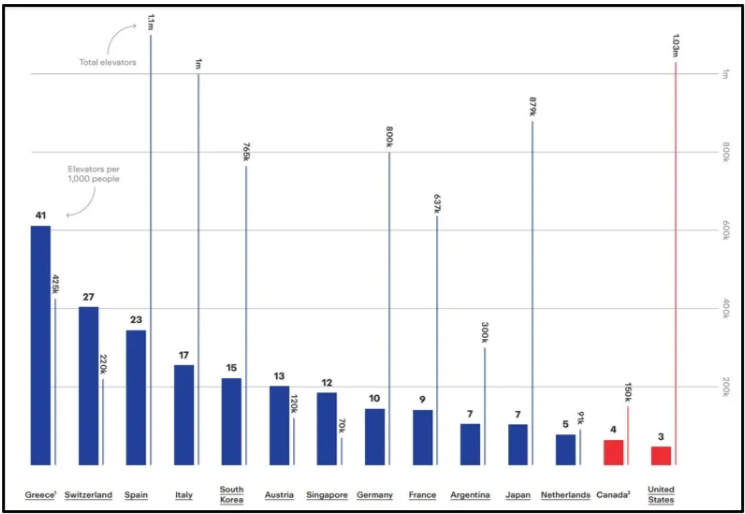

As the Center for Building in North America points out, the United States has the fewest elevators per capita of any other high-income country, with three elevators per 1,000 people. Other countries like Greece have 41 elevators per 1,000 people, Switzerland has 27 elevators per 1,000 people, and South Korea has 15 elevators per 1,000 people. This shortage of elevators is caused by codes and regulations that force elevator cars to be at least twice the size of elevator cars in Western Europe, which leads to the installation of new elevators costing at least three times as much as they cost in Western Europe and East Asia.

The cost of American elevator installation and the extra leasable space American elevators take up means developers really only add elevators in taller mid-rise and high-rise residential developments that serve more units (the general rule is at least 40 to 50 units). Functionally, the size and cost of American elevators, together with other regulatory and market forces, pushes housing developers to build townhouses instead of flats or small apartment buildings in low-rise multifamily zones and reduces the amount of accessible housing available.

Stephen Smith, the executive director of the Center for Building in North America, said it best during the Senate housing committee public hearing for SB 5156. “There are practically no new walk up apartment buildings in Western Europe, while they are still common in the United States and in Washington State. It’s not good for disabled people. It’s not good for elderly people. It’s not good for parents of young children. It’s not good for first responders. The situation is unbecoming of a country as wealthy as we are.”

The recommendations would right-size elevator sizes specifically for smaller multifamily projects with six to 30 units, increasing accessibility in new multifamily buildings. The smallest elevator size draws inspiration from the typical dimensions of elevators in Europe. The medium elevator size draws inspiration from the typical dimensions of elevators in South Korea, which, while being smaller than US elevators, still typically allows enough room for wheelchairs to turn 180 degrees inside the elevator. The largest elevator size is a hybrid between European and South Korean elevators that can accommodate a fully flat stretcher, which maintains a requirement of American elevator codes.

Questions around safety and whether these changes are safe are bound to come up. The report and citations cover some of the safety concerns in more detail. However, people should also ask themselves whether it is really believable that people in other high-income countries live in deadly, dangerous, death-trap buildings? Was the hotel or short-term rental you, a family member, or a friend stayed in when visiting internationally structurally dangerous, and you were just lucky to return home alive? Would these countries’ people let their governments not do anything to improve building safety if this were a genuine concern?

People in cities across the world live full, satisfying, and safe lives in part because their building codes allow these housing options to be abundant in their housing market. Also, Seattle is a rich city in the richest nation in the world. The idea that countries and cities not as wealthy as us can build at scale safe, desirable, taller buildings with a single stair, scissor stair, or smaller elevators, but we, Seattle, can’t do so, just doesn’t hold up.

Seattle, again, has the opportunity to innovate and encourage new construction, higher-quality city living, and accessible housing. I hope we choose to act sooner rather than later.

Enjoy a sampling of housing we’re missing out on

This article is a cross-post that first appeared on Markus Johnson’s Medium page.

Markus Johnson is an advocate for better, desirable, convenient cities. He is a professional urban planner that is particularly interested in housing, transit, and bike lanes.