When bicyclists started rolling into the small farming town of Tekoa in 2017, farmer John Heaton took notice. In a place where the wheat sways more often than people come and go, it was hard to miss.

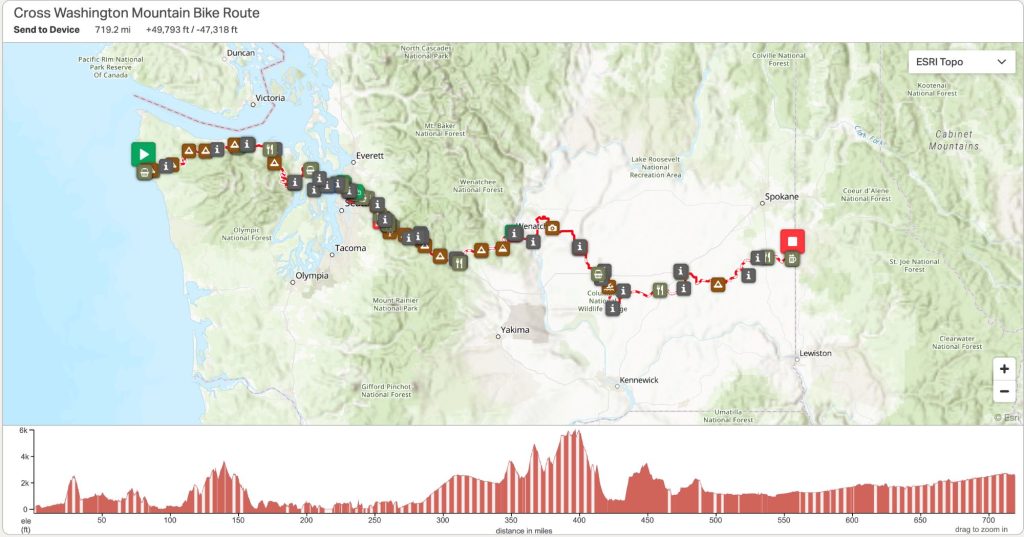

The next year, Heaton couldn’t help himself and approached the riders. That was the first time he heard about the Cross-Washington Mountain Bike Route (XWA), a 700-mile bikepacking race that stretches from the town of La Push on the northwest tip of the state to Heaton’s hometown of Tekoa, on the Idaho border south of Spokane.

“We’ll take any kind of excitement we can get around here,” Heaton said.

Every year since, Heaton has become a “dot watcher,” someone who tracks the progress of participants via GPS as they make their way across the state.

In a gravel parking lot at the center of town, it’s become tradition for him to welcome riders with the ringing of his cowbell and loading bikes on the back of his truck, giving cyclists a ride to Spokane.

“It’s kind of like a thing of pride,” Heaton said. “I have to be down at the finish line, by God, no matter when they arrive. I’ll be there at two o’clock in the morning on a Wednesday.”

Heaton’s experience is just the tip of a larger story: how the slow-growing sport of bikepacking is connecting communities across Washington, and drawing both national and international attention.

Stitching of the Route

The growing stream of dusty cyclists arriving in Tekoa each spring can all trace their journey back to one person: Troy Hopwood.

At the age of four, Hopwood was crashing bikes into his neighbors’ front yards in Oregon. From there, his love for biking led him to compete in mountain bike races in college, and eventually to a documentary about the Tour Divide, the longest mountain bike route in the world.

After being voluntarily laid off during Microsoft’s recent mass firing, Hopwood can now focus his full attention towards bikepacking: a mashup of mountain biking and backpacking that requires cyclists to carry all their gear, including tent, sleeping bag, food, water filter, tools, for days or even weeks at a time. For many, it’s an escape from modern convenience; for others, it’s a grueling form of sport.

In 2016, Hopwood stitched together a route, mapping every forest road, gravel trail, and bike path that could link the Pacific Ocean to the rolling Palouse.

The result was the XWA.

Riders traverse everything from misty rainforest and snowy mountain passes to barren scablands and wheat-covered hills. It’s not for the faint of heart. The route often demands dealing with unpredictable spring weather in the west and rocky, unmaintained paths in the east.

“People who live in the state oftentimes don’t even realize how diverse the state is until they take on the route,” Hopwood said.

He wasn’t sure anyone would want to join him.

But in 2017, a small group of riders took on the route together in what’s known as a “grand depart,” a mass start in La Push. Since then, the race has quietly grown, year by year. In 2024, 54 riders registered; this year, that number has grown to 138.

Attracting riders from across the U.S. and even abroad from South Africa to the United Kingdom, the route is also becoming a destination for tourists who are looking to experience what Washington can offer. Cyclists from around the world start by facing the unpredictable weather of the Olympic Peninsula.

Stephen Page is participating in the race for a second year, this time with a friend. Serving as an escape to his busy and structured life in Canada, Page returned to race and reconnect with nature.

This year also saw more women participating. Emanuela Agosta, a member of the Mountaineers bikepacking division committee, acknowledged the challenge that women still face in male-dominated sports, but said it’s not impossible.

“It’s not as scary as it sounds. It’s just putting some gear together and going on overnights,” Agosta said. “You racing is all subjective… It’s a different challenge for everybody.”

Keeping the state connected

Not all is smooth biking, however. Throughout the years, the eastern section of the route has faced challenges.

After the last train ran on the Milwaukee Railroad that connected Seattle and Chicago in 1980, contention arose over who would own the land where the rail tracks lay.

Chic Hollenbeck founded the John Wayne Pioneer Wagons and Riders Association, a group that has done an annual pilgrimage on the trail since the 1980s, and lobbied against landowners who wanted the trail to become private land.

Hollenbeck’s group advocated to keep the John Wayne Pioneer Trail public, which much of it was for decades. But in 2015, legislation by Rep. Joe Schmick (R-Colfax) along with Rep. Mary Dye (R-Pomeroy) would have closed a 130-mile section east of the Columbia River and given it to farmers citing maintenance costs, underuse, and crime.

The legislation didn’t pass due to a typo.

Now named the Cascade to Palouse State Park Trail, which mostly covers the scabland section of the route, Hopwood said one of his motivations in creating the XWA was to protect this trail from future legislation that could take it away from the public.

Audra Sims, area manager for Washington State Parks who manages 10 different parks in the southeastern region of the state, including the Palouse to Cascade Trail, shared her excitement about the development happening in the area.

“A lot of enthusiasm and support for different sections of the trail and all of those things combined can have some impact on how certain developments happen and where and when they happen,” Sims said.

In 2022, the Tekoa Trestle opened to the public, offering additional access to locals. Sims said that current trail and route developments adjacent to rural communities could bring economic development.

Washington resident Robert Yates, who was involved with the Palouse to Cascade Trail Coalition, said that rural communities are becoming more open about outsiders and the potential of the route despite the lingering oppositions of some landowners.

The 2020 Economic Analysis of Outdoor Recreation in Washington State shows that bikers riding on paved and gravel routes generated approximately $1.5 billion worth of business.

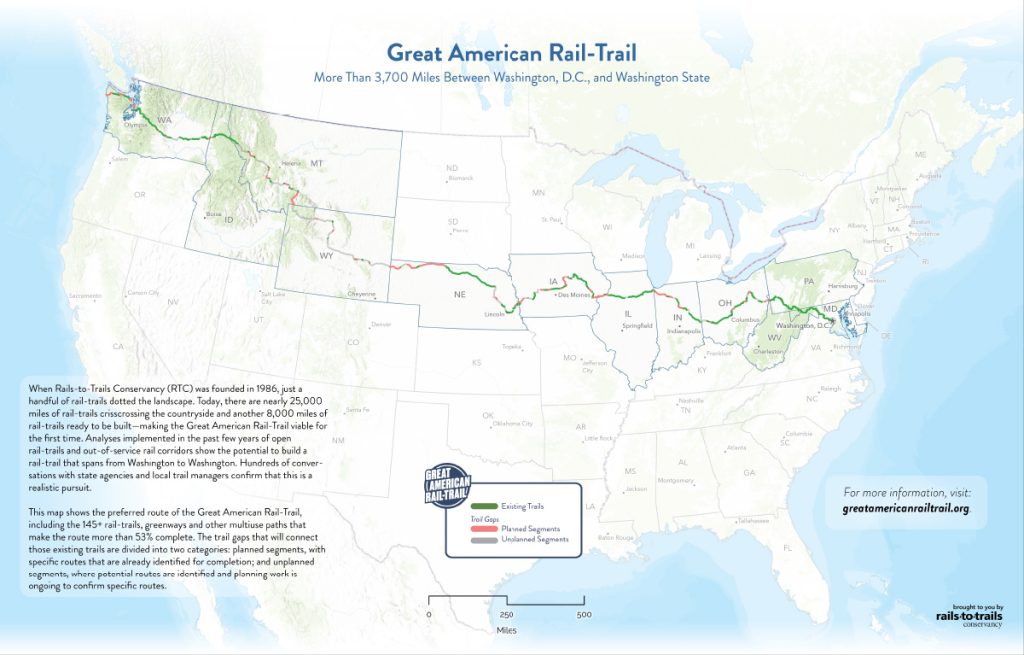

The trail is also part of the 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail, which aims to connect Washington, D.C., and Washington State by revitalizing old rail corridors that could funnel in more visitors across the country. In 2023, a $16 million federal grant advanced work to build out the Olympic Peninsula section of the trail.

It’s a free ride, but respect is required

There are no fees or sign-ups required to participate in the grand depart, which usually takes place during the third week of May. However, riders are encouraged to stay connected on the Facebook group on route changes, trail conditions, and GPS tracking options.

A permit is required for the Palouse to Cascades section of the route, which also provides riders with gate codes necessary for access along parts of the trail.

Riders can take on the XWA at any time of year. For those who want to experience the journey across Washington on a less demanding route, Hopwood has created the XWA Lite, a version that follows a more direct path to the Idaho border.

Whether riding the entire length or just a portion of it, riders should be aware of their skill level and what they are signing up for.

“This ride is 100% self-supported,” Hopwood said. “Nobody will be looking out for your safety other than you. I do not guarantee the route is safe. In fact, this is a dangerous activity. There is a very high likelihood you will get hurt or worse.”

Ultimately, Hopwood often reminds riders to respect the trail by following Leave No Trace principles and being mindful of local residents and private properties near the route.

“Waiters, cashiers, and others don’t care that you are trying to set a personal record,” Hopwood said. “You can tell people you are in a hurry, but the small towns you pass through operate at a different pace. Be patient.”

From Competition to Connection

But for some, it’s not even about the money or the biking.

Flapping in the western winds of La Push, a yellow flag bearing a huge smiley face and a printed “XWA” was propped on the back of Brook Muldrow’s RV. He had driven all the way from Oklahoma to serve as a trail angel, someone who supports riders along the route.

A massage gun, thoughtfully arranged high-calorie snacks on the table, and a watchful eye anticipating muddy riders showing up around the bend make it clear Muldrow has done this for years.

“I enjoy being able to provide some of the supplies that the riders need at a critical time,” Muldrow said.

Trail angels like Muldrow are scattered throughout the stretch of the trail from folks in North Bend to Tekoa, oftentimes just leaving marked containers filled with food and supplies outside for bikers.

Among the riders who have come to cherish the XWA race for more than just the competition is Eric Miller.

Miller has taken part in the race seven times, having become a regular presence over the years. At first, he was drawn to the challenge primarily to compete – both against himself and against others on the route.

“It started as a personal challenge, something to prove to myself,” Miller said. “But what kept bringing me back year after year wasn’t just the race itself, it was the people.”

During the pre-race meeting on May 17, hugs and huge smiles rivaled the warmth of any parka jacket present. For Miller and other riders, XWA has become a yearly reunion of friends, a time to reconnect and recharge.

Through trail angels like Muldrow and the riders he met on the route, Miller discovered a tight-knit community that transcended competition. The shared struggles, stories, and moments of support formed lasting friendships that gave the race a new meaning for him.

That same spirit has inspired people like Heaton, who has welcomed strangers year after year with cowbells and open arms.

After years of cheering from the sidelines, Heaton dreams of participating in the race himself next year – not just for the challenge, but to become part of the community that’s already changed his town and maybe even him.

Juan Jocom is a Filipino multimedia journalist based in Seattle. A University of Washington graduate, his work has appeared on Seattle Met, South Seattle Emerald, Real Change, The Ticket of Seattle Times, International Examiner, The UW Daily, The Nudge.