A newly signed Washington State law aims to “improve safety for young drivers” by expanding access to driver’s education and raising the minimum age at which new drivers can get a license without completing a formal driver’s education course. Today’s minimum age of 18 will be raised to 22 over a phased implementation period, eventually mandating all new drivers ages 16 to 21 complete a comprehensive driver’s education course before getting their license.

Beginning in 2027, drivers ages 18 to 24 who incur two driving infractions will also be required to take a safe driver course within 180 days of notice or see their license suspended. Starting in 2031, the law modifies the requirement to a condensed traffic safety education course for young adult drivers with two moving infractions.

It may come as no surprise that adolescent drivers are more at risk of being involved in a serious collision than older, more experienced drivers. A relative lack of experience coupled with a developing brain impacts one’s risk perception and decision-making.

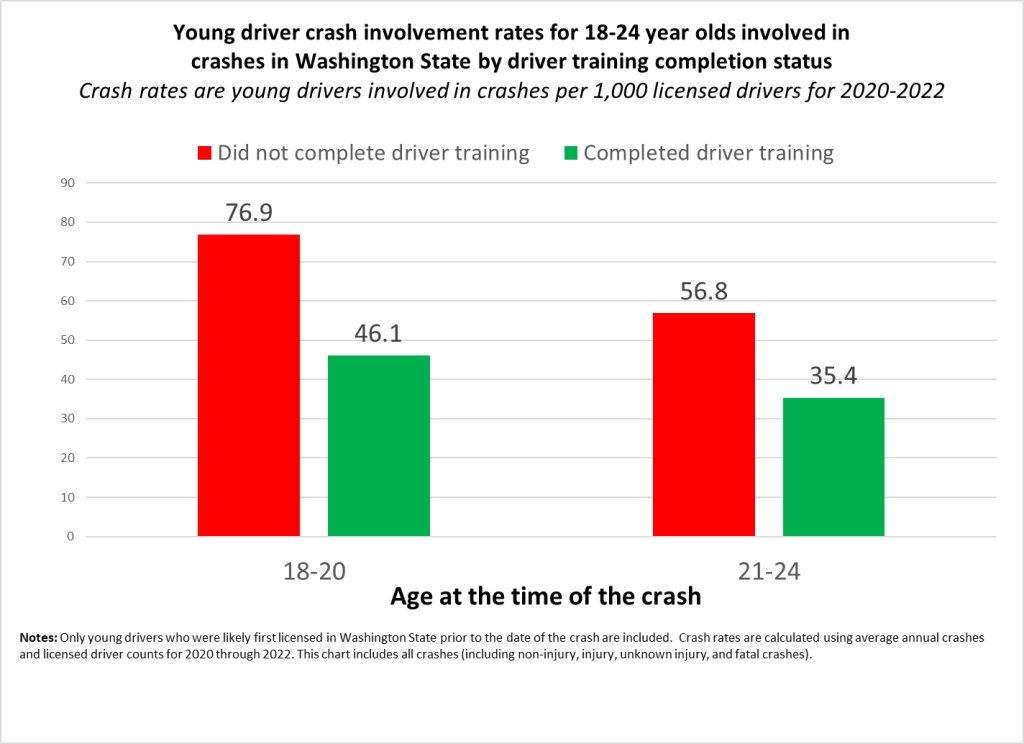

A crash history analysis published in 2023 by the Washington Traffic Safety Commission uncovered something more. In Washington State, novice drivers between 18 and 24 years old who don’t complete a driver’s education course are at a 70% higher chance of being involved in a collision resulting in major injuries and/or fatalities than their peers who took driver’s ed.

The Washington Traffic Safety Commission published a safety action plan in 2024 calling for a driver education overhaul similar to what ultimately became Everett Rep. Brandy Donaghy’s House Bill 1878. The plan also called for lowering the state’s blood alcohol limit to 0.05, but state legislators balked at that particular reform this session.

Driver’s education is more than learning how to operate a vehicle – it encourages reflection upon how one’s personal values and experiences influence decision-making behind the wheel, and helps to instill a sense of personal responsibility as part of the greater driving collective to keep roads safe for all people using them .

Washington State had previously required all individuals getting their first license at ages 16 and 17 to complete a 30-hour in-classroom knowledge course and 6 hours of behind-the-wheel instruction. For 18-year-olds and older, these requirements are lifted, and a person can technically acquire their license with the minimal knowledge and skills required to pass the written knowledge test and driving exam.

Janine Koffel, the Distracted Driving, Speed Management, and School Zone Program Manager at the Washington Traffic Safety Commission, holds a doctorate in prevention education and has been working in the field for 40 years.

“When a young person whose brain is still under construction [does not] get driver training,” Koffel said, “they’re at a sort of fundamental disadvantage because their brain is still evolving and they don’t have any contextual learning to compensate for those emerging skills.”

The complex task of driving relies on key executive functions: risk identification and evaluation, delayed gratification, and emotional regulation. These functions occur in the frontal lobe, one of the final regions of the brain to finish developing in adolescence, and development usually slows down around the age of 25. Because of this, adolescents’ brains are still malleable, which is why it is so important to introduce and ingrain the knowledge, skills, and habits of safe driving before development is complete.

High costs are a barrier to safe driving courses

Students (and/or their parents) often have to shell out over $1,000 for driver’s education expenses on top of examination and licensing fees. The cost of a full driver’s education course in Washington State, which includes a minimum of 30 hours of classroom instruction and 6 hours of behind-the-wheel instruction, ranges from $600-$800 depending on the driving instruction company. Additional driving practice sessions often cost around $90-100 per hour.

The fees associated with the written and behind-the-wheel exams can amount to over $100. These costs are about the same when taking these exams at the Department of Licensing (DOL). Some driving schools charge additional fees to students who choose to use one of these companies’ vehicles to take the test if they don’t have access to one otherwise.

Cara Jockumsen, a traffic safety specialist with the DOL who worked on the new bill, explained that for people in rural communities where the spatial scale is much larger and incomes are generally lower than in urban and suburban communities, driving is more of a necessity for everyday life, and these costs pose a significant barrier. For low-income students in urban and suburban areas where the cost of living is generally higher, these costs pose a barrier as well.

“The shift from school-based driver education to a privatized system over the last couple of decades has created some challenges that HB 1878 aims to address. Courses have become prohibitively expensive for many low-income students, and many parts of the state lack driver education programs. Private schools will typically locate where demand is greatest,” said Mark McKechnie, external relations director at the Washington Traffic Safety Commission. “It is important to provide stipends to low-income students because it helps make them safer drivers. And it should also increase demand in currently underserved areas of the state, with additional resources to attract more driving instructors to these areas.”

The safety commission expects the benefits to be widespread.

“These changes benefit everyone on our roads throughout the state,” McKechnie said. “Young drivers who have not had driver education are involved in far more crashes than their peers who have completed an approved course.”

The business of driver’s education sometimes seems to compromise its intended purpose: to ensure drivers are equipped with the knowledge, skills, and decision-making capability to safely operate a 2,500+ pound machine.

Another major component of this new driver education and safety bill seeks to address the cost of instruction by introducing a scholarship voucher program through the DOL to cover the average cost of driver’s ed for eligible individuals living in low-income households. The DOL will be able to issue vouchers to eligible novice drivers up to age 25, encouraging more young people to seek out driver’s education even after they are no longer legally obligated to. Today, such vouchers are offered through the Department of Social and Health Services and the Department of Children, Youth and Family Services.

In order to fund the voucher program, the DOL will raise some of the fees involved in the licensing and registration processes by no more than $15 per fee.

All accredited driver’s ed courses in Washington State require students to attend all 30 hours of classroom instruction in person, posing another barrier for many trying to complete driver’s ed. This means that people in rural areas who live far from the nearest driving school will have to find a reliable way to commute to and from their course, which usually lasts roughly two months, with no online-accessible alternative. Twenty states already accept hybrid online driver’s ed courses, and some states allow students to complete driver’s ed instruction virtually and at their own pace.

This law allows the DOL “to authorize portions or all of a [privately offered] course to be online, self-paced,” Jockumsen said. “Any of the topics could be covered online, self-paced,” or online in a synchronous format.

This aspect of the bill has drawn criticism from some driving instructors.

Alex Hansen, President of the Washington Traffic Safety Education Association (WTSEA) and veteran driving instructor, argued in a letter about HB 1878 published online in March that returning driver’s education to public schools is the “most equitable way to reach all novice drivers,” regardless of systemic barriers. He criticized the bill for not suggesting this.

Furthermore, Hansen points out that HB 1878 only encourages online components for private driver training schools and argues that it should also include offering online instruction in public schools, so long as it only applies to “limited modules that may lend themselves to that type of instruction. But never for a full course.”

Returning driver’s education to more public schools – the 30 hours of classroom instruction and six hours of behind-the-wheel training – was discussed in the state legislature during a House Transportation Committee session in January. While transportation experts largely agree upon the access benefits of returning driver’s education to public high schools, feasibility is highly uncertain in the face of a projected multi-billion-dollar budget deficit statewide, Koffel said.

“I really value in-person education as a teacher,” Koffel said, adding she recognizes the pros and cons of in-person, synchronous online, and asynchronous online education, “but I also recognize that […] either strategy has advantages for different kinds of learners.”

Grappling with a shortage of driving instructors

Students’ access to driver’s education also depends on the availability of instructors. There are two routes to become a certified driving instructor in Washington State –the first of which involves leaving the state.

“If you’re lucky,” Jockumsen said, prospective instructors can enroll in Western Oregon University’s driving instructor program. Only a certain number of Washington applicants are accepted into the program yearly. Oregon applicants are usually given priority, so if they reach capacity with Oregon applicants, Washington applicants won’t be accepted during that cycle. The other way to become an instructor is by training with and getting certified by an existing private driving instruction business. These two main routes often require prospective instructors to cover application, training, examination, and licensure fees, which can amount to over $1,000 out of pocket.

The Washington DOL does not offer financial assistance to cover these costs; however, some of the more established private driving schools can encourage recruitment by offering financial incentives to prospective applicants.

For instance, Olympic Driving School’s incentive package covers all training, initial licensing, application, and fingerprinting fees and pays trainees the state minimum wage while they receive the 100+ hours of instructor training. Additionally, the incentive structure offers a raise upon licensure as an instructor, a completion bonus after 90 days of holding an instructor’s license, and additional raises upon licensure as a road test examiner and once able to offer one-on-one lessons to new drivers.

To stimulate competition in the driver’s education industry, the DOL recently launched the Driver Training School Business Guidance Pilot Program, which offers guidance and training for people seeking to own and operate a private driving instruction business. However, the program does not offer any financial assistance.

Stalled progress on Target Zero safety campaign

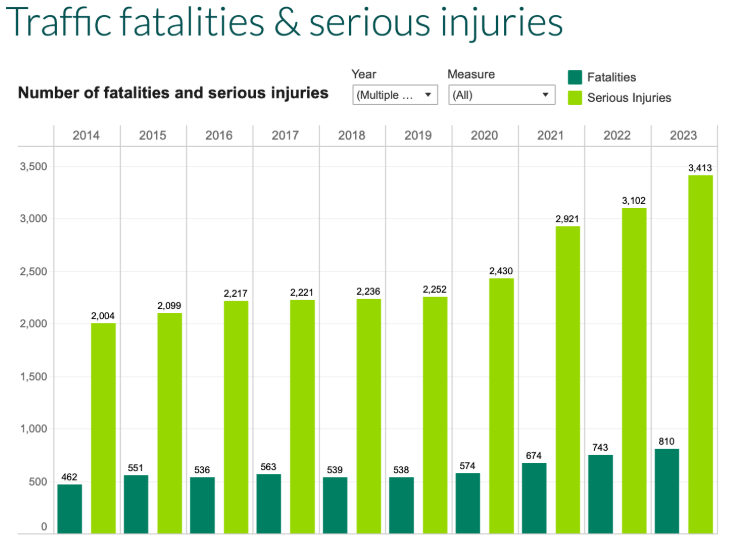

This young driver education and safety bill is but one avenue through which Washington State hopes to achieve Target Zero by 2030, eliminating deaths and serious injuries on its roads. Unfortunately, rather than trending toward zero, state traffic deaths are on an upward trend despite the decades-long Target Zero campaign, which is leading some lawmakers to call for reforms — or a more realistic goal.

As part of its Target Zero efforts, the state has made some headway on traffic enforcement and education measures. However, safe streets advocates have warned that the state has neglected safety-focused street redesigns, which they see as the key ingredient to reach the goal, as the state continues to lavish investments on highway expansion.

All road users play a part in keeping the roads safe while getting where they need to go. As long as driving is the most convenient mode of travel in Washington State, many people will drive. To develop the skills and habits to prioritize safety while driving, barriers to accessing driver’s education must be brought down. This bill is set to begin a long journey of making driver’s education more accessible to Washington residents, thereby making the roads a little less dangerous.

Hopefully, complementary safe streets investments will be on the way, as well.

Correction: This article was updated on June 16th to remove a quote mistakenly included from an on-background source and replace it from one from Mark McKechnie, the external relations director at the Washington Traffic Safety Commission. We regret the error.

Noa Resnikoff

Noa Resnikoff is an undergraduate student at the University of Washington majoring in journalism and public interest communications with a minor in urban design and planning. She was born and raised in San Francisco where her love for public transit and passions for urbanism and traffic safety took root. You can find her roaming around the U District on her sticker-covered bike named Shprintze.