If someone complains about the “Seattle freeze,” they’ve likely never strolled through their neighborhood art walk. The city offers few opportunities better suited for building community and sparking conversation with strangers.

The Central District Art Walk demonstrated this on June 6 when a few dozen art lovers gathered in a vacant commercial space adjacent to the nonprofit Arte Noir’s gallery in Midtown Square at 23rd and Union, which the nonprofit had activated for the “Baggage Claim” fashion show.

The audience assembled in the unfinished space, lit solely by the evening sun, to watch 12 Black models cycle through, appareled in timeless wares that personal stylist Justin Leggett curated from the collections of local vintage stores: Jamil, The Lemon Grove, and Throwbacks Northwest. Each model entered carrying a retro handbag packed with tops, accessories, and outer wear that they’d slip into to modify the fit they initially wore, before strutting out, leaving their luggage behind, only to return a few minutes later wearing a new base outfit and toting yet another bag perfectly complemented to whatever they now wore.

When the audience wasn’t admiring Leggett’s eye for fashion, they chatted amongst themselves and browsed the clothes racks the retailers had installed for a one-night pop up to accompany the show. The event, like so many art walk activities in the Central District, brought together all the things that Jazmyn Scott, Arte Noir’s executive director, said she loves: “art, Black people, my community.” Those are the very things that inclined her to accept the role leading the organization after her mother, Vivian Phillips, founded it in 2021.

Phillips, Scott, and Arte Noir have been vital to rejuvenating the Central District art scene as they’ve worked alongside other arts organizations, restaurants, and shops to create a vibrant hub at an intersection essential for Seattle’s once Black-dominated enclave. In Midtown Square, depending on the day, you can catch a concert, take a dance lesson, attend a yoga class, or pull up to a party. As a former program director, Scott said she regularly asks: “What are the ways that we can reel people in and sometimes give them something that they never knew they were going to get?”

Arte Noir is just one of several community-first arts spaces throughout the city that exemplifies how the cultural sector brings communities to life, and helps neighborhoods recover from down turns—or even help prevent them from happening. Other organizations and spaces that do this particularly well are Base Camp Studios and Common Area Maintenance, each of which operates two locations in Belltown.

(Disclosure: Syris Valentine is a paying member of the writers program at Common Area Maintenance.)

When Nick Ferderer and Base Camp Studios, the nonprofit arts collective he founded, first began cleaning and renovating their second space on the corner of 3rd and Stewart, the former storefront had sat vacant and vandalized for three years—just one of many 3rd Avenue businesses shuttered by the blight of downtown closures that hit during the pandemic lockdowns. Bergman Luggage, the previous tenant of Base Camp’s new gallery whose sign still adorns the corner of the building, was just one of many businesses on that stretch of 3rd that closed during the pandemic.

“For the most part,” Ferderer said, “[the Third Avenue Cafe] was the only thing that had any activity on the ground floor” when Base Camp moved in.

Over three months at the end of 2023, Ferderer, with some support from friends and family, hauled 55,000 pounds of trash out of the building’s second floor. That trash went on to form the core of the “Ghosts of Belltown” show that both mourned and commemorated the neighborhood’s legacy. But an avant garde art show wasn’t his main motivation: he wanted to clear the upper level quick as he could to convert it into a collection of private art studios to start bringing the building back to life. While cleaning out the mass of debris, Ferderer found among it all a permit from 1996, which led him to believe that the second floor may have lain vacant for decades longer than the Bergman storefront.

These kinds of closures and vacancies can have a negative ripple effect, Ferderer said, with foot traffic slowing down and potential public nuisances creeping in. But a similar effect can ripple in reverse as organizations and businesses start moving back in. He’s seen this happen over the two and a half years since Base Camp Studios 2 first opened to the public, with businesses popping up on both sides of 3rd, and Cannonball Arts converting the former Bed Bath and Beyond just down the block into a 66,000 square foot contemporary arts center.

Ferderer was quick to add that he doesn’t believe Base Camp is the sole catalyst for any of these openings. But, he said, when someone knows they won’t be moving into a ghost town, it can make the decision to set up shop somewhere just a little bit easier.

Because artists and creatives have a particularly scrappy, do-it-yourself attitude to creating spaces and conjuring beauty with whatever resources they happen to have at hand—and bring their community along for the ride—the sector has been a major part of the mayor’s Downtown Activation Plan.

One program in particular has supported this: Seattle Restored, an initiative led by Seattle’s Office of Economic Development and two nonprofit partners, Shunpike and Seattle Good Business Network. The effort has tapped artists and small businesses to activate vacant storefronts at 56 locations across the city through art displays, pop-up shops, and, in some cases, long-term leases. Seattle Restored has even partnered with Base Camp to subsidize studio rentals for around a dozen artists at the 3rd Avenue location.

This has been critical not just to revitalize downtown after so many businesses closed, but because the pandemic hit the city’s art sector itself particularly hard. Downtown Seattle is the artistic core of the Pacific Northwest. Two thirds of creative careers in Seattle are housed there, according to the Downtown Seattle Association, and the neighborhood accounts for around 20% of the region’s artistic workforce. As a share of local employment, Seattle ranks as the city with the fourth largest creative economy in the country, beating out Nashville, Atlanta, and Chicago, among others.

But Covid-related disruptions caused nearly half of all creative workers downtown to lose their jobs. Thankfully, the arts scene has nearly returned to pre-pandemic levels thanks in part to Seattle Restored and other efforts, like the Hope Corps grant program run by Seattle’s Office of Arts and Culture, which has funded artists and creatives across the city for three years running and which will host dozens of events this summer. But many artists and organizations still feel like the city can do more, even as they applaud what’s already been accomplished.

###

In Belltown, the city has an opportunity to expand the impact of Seattle Restored and related programs to further support the efforts of local arts organizations to revitalize downtown. There, a historic building called the El Rey may soon be torn down after a series of misfortunes befell it, but a dedicated group of artists dreams of rescuing it from demolition.

Around a year after SOUND Behavioral Health acquired the El Rey, which served as a residential facility for up to 60 people in need of mental health care, the nonprofit had to shutter it after deferred maintenance led to sewage leaks and plumbing troubles. Sometime later, a vandal broke in and tore through the building to scavenge a meager amount of saleable copper, all while inflicting a million dollars in damages. Because the plunder impaired the main fire and electrical panels, water and electricity to the building had to be shut off, and SOUND Behavioral Health became responsible for placing the building under around-the-clock fire watch at the cost of around $45,000 per month, the group said.

The maintenance required to make the building once more fit for the services SOUND Behavioral Health provides, alongside the ongoing security costs, led them to apply for permits to tear down the historic 115-year-old building because, despite the extensive retrofits that have aimed make the structure earthquake-ready, demolition is the only option they say they can afford.

The arts-nonprofit Common Area Maintenance, often simply referred to as CAM, operates one of its shared studios in a commercial space next door to the El Rey. Soon after their leadership heard that the building may come down, CAM got involved in conversations about what it might take to save it. Those conversations emerged in part because of concerns that the demolition could affect the integrity of the building that CAM currently occupies, which was built at the same time as the El Rey, but also because Timothy Firth, CAM’s founder and executive director, recognized what the building could mean for the organization and the community if they took it over themselves.

“Demolition was one of the only options that [SOUND Behavioral Health] had,” Firth told The Urbanist, “until I approached them and said, ‘Hey, we could save it for a community-benefit purpose.’”

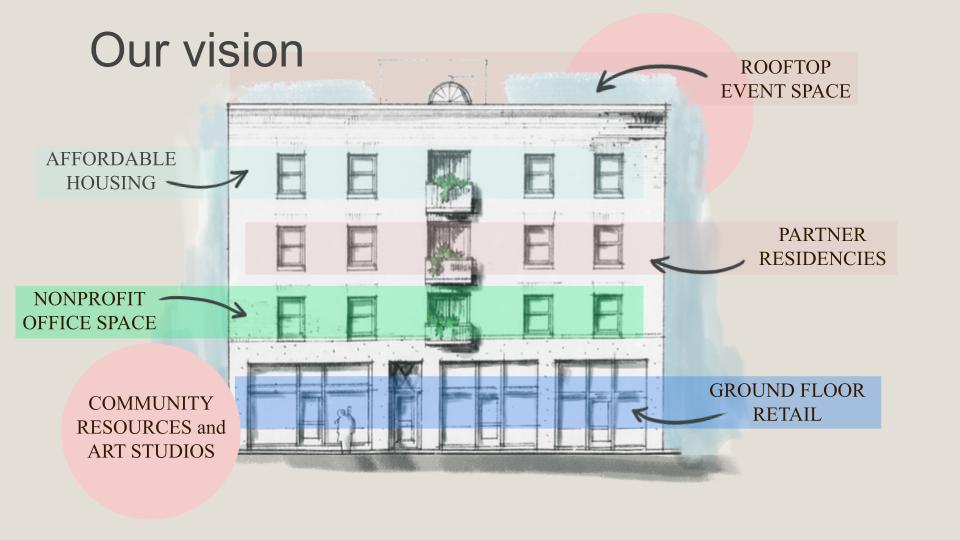

Firth and CAM have imagined manifold community benefits that would bring a unique use to each of the four floors of the building, plus the roof and the level below grade. The basement could easily become a ceramic studio and fabrication space for CAM members, Firth said; the first floor would provide storefronts, community resources, and art studios; the second floor, nonprofit offices; the third, residency space for artists and writers that partner organizations bring to town; the fourth, affordable housing; and the roof, an intimate event space with views of the Space Needle, Elliott Bay, and the Olympic Mountains.

Firth said that SOUND Behavioral Health and the contractors they’ve hired for the demolition already love the vision that CAM has for the El Rey. But to realize it, CAM has to get the City on their side as well.

Right now, SOUND Behavioral Health has a $2 million loan on the property held by the Seattle Office of Housing, and riding along that loan is a covenant that requires the building owners to provide 60 units of housing affordable at 30% area median income. That requirement makes the El Rey almost impossible to sell, particularly given the building doesn’t even host 60 individual apartments, and SOUND fulfilled the quota by providing multiple beds in the same unit.

But, as Firth has talked more with the Office of Housing, the office has expressed a willingness to facilitate the sale of the building to CAM, even though their vision for just 10 affordable housing units doesn’t meet OH’s needs. That still leaves CAM with the challenge of dealing with the loan. “For us,” Firth said, “the idea of buying this building for $2 million is completely out of reach.” But they’re eager to pursue one path in particular: getting the city to lift the housing covenant and facilitate the sale of the building for a single, symbolic dollar at the same time that it defers the loan for 40 years of public benefit, at the end of which the city would waive the loan. It “happens all the time,” Firth said.

For instance, a similar deal was struck between the city and Africatown Community Land Trust, so the Black-led nonprofit could transform the historic Fire Station 6 into a community center.

(Syris Valentine was previously employed at Africatown Community Land Trust, where he supported the renovation of Fire Station 6.)

If CAM could convince the mayor and city council to agree to a deal like that, the last obstacle would be raising the estimated $3.5 million required to renovate and restore the building, “which is absolutely something we can do,” Firth said. The organization would plan to activate the building in stages, Firth said. That would ease the fundraising pressure and allow them to use early successes to attract more grants and donations to bring the rest of the building to life.

But CAM is working against a tight timeline. There may be only weeks, months at most, before the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections issues SOUND Behavioral Health its demolition permit, and as soon as they have paperwork in hand, the building will start to come down, because SOUND can’t afford to wait.

Should the miraculous happen and CAM acquire the building, the organization would have ample work ahead. A tour of the building reveals missing ceiling panels, torn out dry wall, dangling wires, and drilled out cement. While some of that damage was done by the copper scavengers, most was done by the contractors as they assessed what it would take to demolish the building, Firth said. Despite the debris, Firth talked on the tour as if the building were already the pristine arts and community space he envisions.

Part of his ability to so crisply visualize what the El Rey could become comes from his experience taking vacant, dusty spaces and enlivening them. This is what he and his community did when they occupied their first location 10 years ago on 2nd between Blanchard and Lenora, and it’s what he is currently doing at their second location on 1st and Vine. Both of those spaces had been empty for years before CAM took them over, and before Firth and company put in the same sweat equity that Ferderer has given to Base Camp Studios.

Pursuing these activations is important not just in the short term for providing continued recovery post-pandemic, but for the future of the city as well, especially with the World Cup coming to town next summer. The international event could bring three-quarters of a million people to Seattle a year from now, and if the city wants to take full advantage of it, Firth said, the best option is investing in more than just temporary, short-term installations but funding projects that provide long-term opportunities for artists to own the spaces they activate, which is exactly what the El Rey represents. Permanence and ownership is also something that Jazmyn Scott emphasized as important.

By supporting the transfer of El Rey to CAM, the city would create a permanent space for artists and creatives in a downtown neighborhood that will bustle during the World Cup, and Firth is confident CAM could easily activate the ground floor in time for next year’s tournament. The alternative, if the mayor and city council don’t help facilitate this deal, could mean yet another empty plot would be left behind to haunt the city’s core—possibly for decades, similar to the Civic Square pit next to city hall.

Ferderer, Firth, Scott, and others interviewed for this story all talked about how vital the arts are not only for the economic activity they spur, not only for the tourism opportunities they create, but for the essential nourishment they provide for the human spirit. As the Office of Arts and Culture’s manager for creative placemaking, Alex Rose put it: “Were we not resourcing arts and culture, we’d be lacking in our human experience, in our civic life.”

Which is to say that Arte Noir, Base Camp Studios, Common Area Maintenance, and the artists and organizations that receive support through Rose’s programs, all collectively make Seattle what it is. And without those groups and without those artists, the city would lose its spark and become a place where people may still live and work but which, ultimately, feels hollow.

“If you don’t value the arts,” Ferderer said, the question then becomes: “what do you value?”

Syris Valentine is a Seattle-based writer and journalist primarily focused on climate solutions, social justice, and the just transition. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, Grist, High Country News, Scientific American, and elsewhere, and you can follow them @ShaperSyris on social media and through their newsletter, Just Progress.