This week, Issaquah councilmembers got a first look at a recommended concept for a potential new bridge over I-90 in Central Issaquah, a facility that city leaders see as an essential component of accommodating a future light rail station in the city. One of the biggest infrastructure projects that the City of Issaquah has ever attempted, the bridge is expected to cost upwards of $110 million in today’s dollars, though it likely won’t actually come to fruition for another decade or more.

Touted as a multimodal connection, the bridge is also a clear attempt to attempt to reduce traffic congestion in Issaquah, creating a tension between doubling down on the area’s current auto-centric uses and the city’s vision for a dense, walkable area around a light rail connection. While the light rail station isn’t set to open until at least 2041, getting the ball rolling now is becoming a priority, in part to get out ahead of any potential property acquisitions that Sound Transit will need to make in the area.

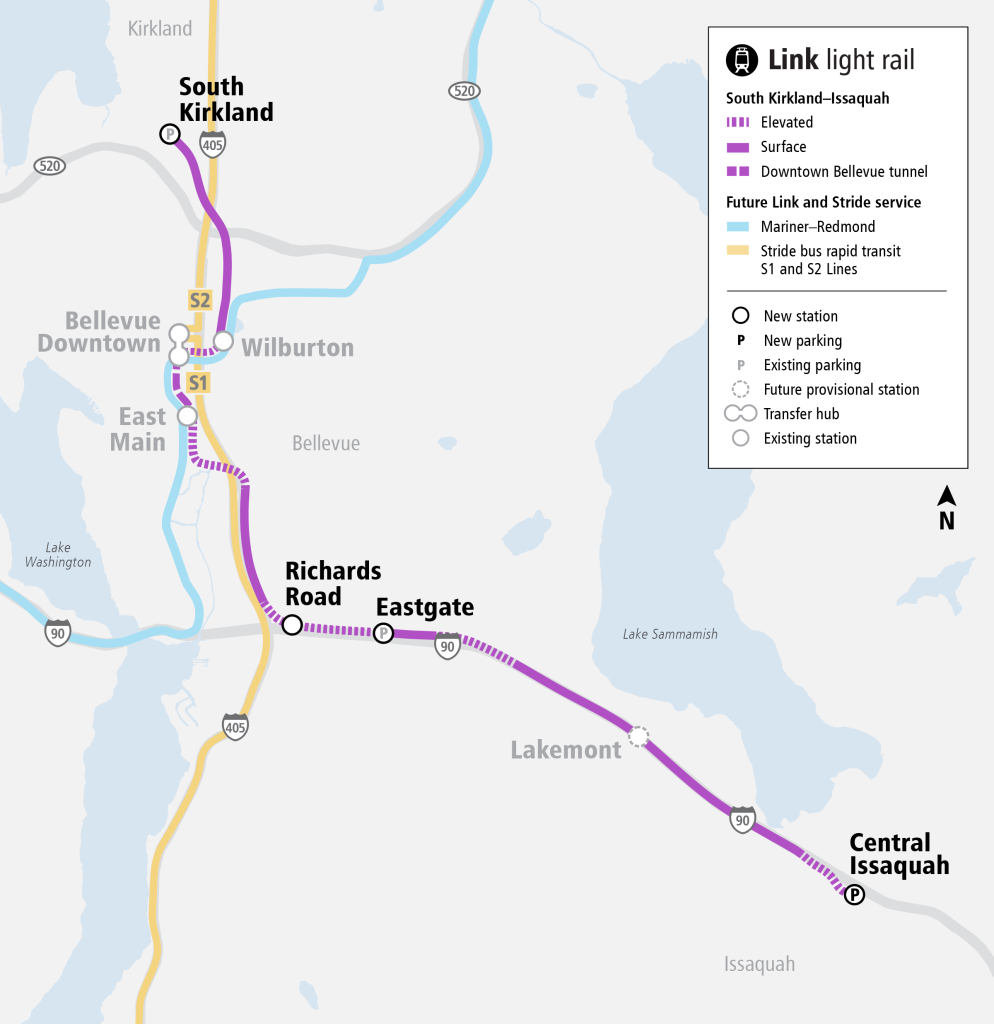

As part of the last Sound Transit 3 rail project planned to start construction, Issaquah’s station will sit at the end of a short line that ties into the existing 2 Line in Bellevue, with new stations at Eastgate, Richards Road, and South Kirkland and service to existing stations at East Main, Downtown Bellevue, and Wilburton. With comparatively lower expected ridership compared to other ST3 lines, the success of South Kirkland-Issaquah Link will depend on building up the areas near the stations, particularly in Issaquah.

The Central Issaquah area, which currently consists mostly of sprawling parking lots and big box stores, is divided in half by I-90, with two highway interchanges at 17th Avenue NW and Front Street N incredibly hostile for anyone not in a car. The city has been trying to prime the area for redevelopment for well over a decade, but other areas in the region have proven more enticing to developers and little redevelopment has occurred.

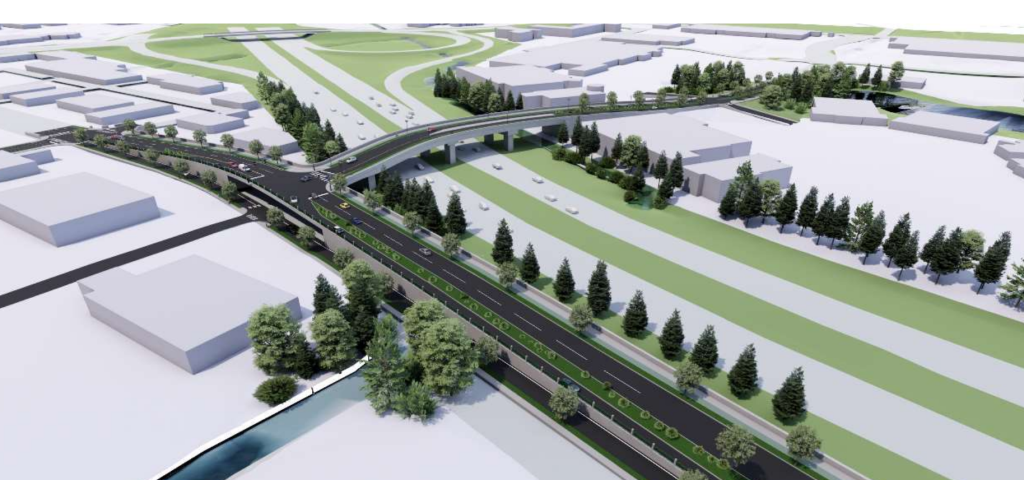

If the area is to transform into a transit-oriented neighborhood, more multimodal connectivity and walkable infrastructure needs to be on the way. Over the past few months, a consultant has been analyzing several different options for bridging I-90 in the general vicinity of an expected light rail station. This week, the council’s mobility and infrastructure committee got a full look at the recommended option picked by Mayor Mary Lou Pauly’s administration: a connection bridging 11th Avenue NW across the highway, with NW Gilman Drive raised up to make the needed change in elevation work.

The new bridge would include three travel lanes, including a center turn lane that converts to a median, protected bike lanes, and a relatively wide sidewalk. As a regional connection, the new bridge would provide a new option for people biking to get to regional trails like the East Lake Sammamish Trail as well as Lake Sammamish State Park.

“This project supports the vision of Central Issaquah of being a thriving and sustainable commercial hub,” Greg Lucas, Senior Transportation Engineer with the City of Issaquah, told committee members. “With the continued growth comes a necessity for safe and functional infrastructure, and this crossing aims to provide that. Additionally, it is designed to complement the future light rail station — while the exact location of the station and the park and ride remains undetermined, the study evaluated comparable footprints of similar stations and park-and-rides across the region to help inform our selection process.”

As part of its scoring criteria to grade the different options, the City looked at both the potential for a new walking and biking connection to reduce both vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and to scale up the percentage of Issaquah residents getting around outside of a car. However, the study also looked at the potential to reduce congestion and improve travel times — without much acknowledgement of the contradictory nature of those sets of outcomes. A bike and pedestrian-only bridge, potentially with transit, wouldn’t induce as much traffic into the neighborhood as a new bridge for general purpose traffic, but it wasn’t advanced as one of the alternatives.

Light rail planning is not set to start in earnest at Sound Transit for several more years, but the City clearly sees an impetus to move fast to avoid being caught up in the work that the agency will have to do to acquire property to build the line.

“Waiting multiple years also increase[s] project costs, as well as working ahead of Sound Transit, while difficult, could be arguably preferable than working behind them,” Lucas said. “Once they get going, you’re — for lack of a better term — left with their scraps. They don’t have the capacity to deal with each individual issue or goal or everything we want from Central Issaquah, they’re going to go fast, and we may not get exactly what we want out of them.”

At this week’s discussion, Issaquah councilmembers weren’t eager to jump right in on a project of this scale, citing a concern over ever being able to fund it. Potential funding sources were cited, including grants from the Puget Sound Regional Council, but the city would likely need to cobble together dollars from a large number of different sources to get across the finish line.

“I just don’t see how this is ever going to pencil out,” Councilmember Chris Reh said. “I mean, I just don’t mean to be Debbie Downer, but the political climate is not such that we’re going to see a great grundle of money coming from the state to fund this. Sound Transit, I would be shocked if they’re going to fund it. […] I want to be all over this, because I love having the idea of another crossing over I-90 living here, but I don’t think there’s any way in the current political climate that’s just ever going to get built.”

That concern was echoed by Councilmember Barb de Michele. “From my own point of view, I’m looking at the price tag on this project and thinking, gee, I just don’t want to make this based on just a couple of meetings and a couple of conversations,” de Michele said.

The timeline being eyed for the bridge would see the city advance design work through 2031, and not acquire any property until at least 2036. After it was decided that the issue should stay in committee, Issaquah City Administrator Wally Bobkiewicz urged councilmembers to zoom out and think on the scale of the project.

“One of the themes you’ve heard from us throughout the discussion, not only with this, but also with light rail itself, is this is a very long game, and that by staging this, spending appropriate time to work with stakeholders in the community, in the region, is important,” Bobkiewicz said. “The political climate does not lend itself to this, but political climates do change, and Issaquah is not going anywhere, and so we would not want to lose this.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.