Despite heavy attention on challenges funding transportation at the state level, shortfalls are projected to hit transit agencies and city transportation networks hardest.

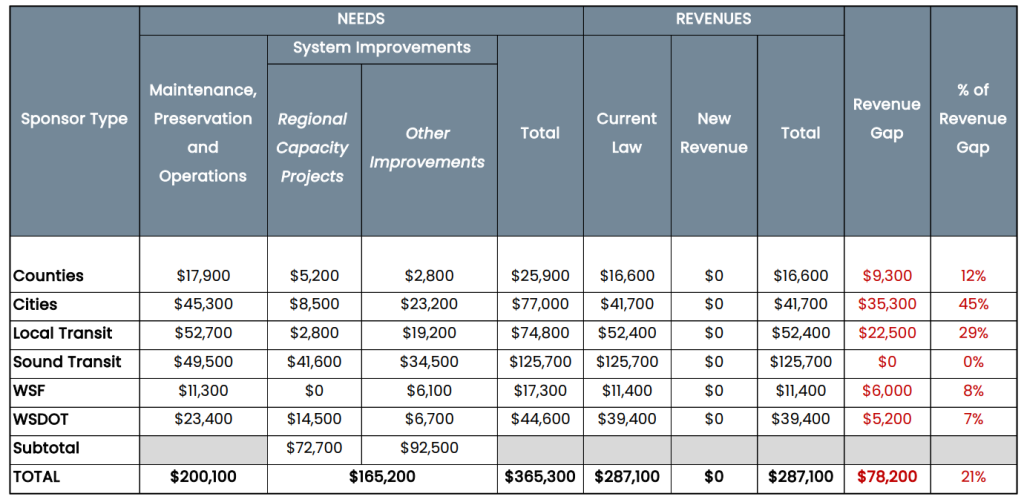

New analysis conducted by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) spells out a significant shortfall in available funding for transportation across all levels of government in central Puget Sound in the coming decades. By 2050, the gap between expected revenue and funding needs for transportation at state and local governments across King, Snohomish, Pierce, and Kitsap Counties is expected to exceed $78 billion — a 21% shortfall.

The giant hole is a stark illustration of the challenges local elected officials face in funding transportation. Many of the roadway facilities built in the golden age of the automobile continue to age, long-dependable revenue sources start to decline, and the costs of projects continue to increase. Earlier this year, state legislators raised taxes and fees across the board to balance the state transportation budget in response to many of these same challenges, but the long-term picture remains incredibly daunting.

At both the state and local level, critical maintenance needs continue to be deferred, increasing both their costs and the chance of any part of the system to fail.

The missing $78.2 billion is out of $365 billion in expected system needs — funds to maintain existing infrastructure, and to add upgrades to improve safety, increase mobility, and attempt to reduce traffic congestion as the region continues to grow. It includes projects like road repaving, bus purchases, ferry maintenance, and replacements for aging bridges.

But hidden behind that overall gap is even more alarming news for both city governments and the region’s public transit agencies: without a significant recalibration of how transportation funding is distributed in Washington, both are expected to bear the brunt of the funding shortfall over that two-and-a-half decades. Transit agencies are facing a $22.5 billion gap — a gap of nearly a third — and city governments are looking at a $35.3 billion gap, a number that approaches half of the expected need. Combined together, cities and transit agencies account for 74% of the overall funding gap.

To illustrate just how dire the balance sheet looks for local cities, consider this: the $45.3 billion expected to be needed to simply keep local streets and bridges in a state of good repair — not counting any safety upgrades or improvements — is less than the collective $41.7 billion in revenue those cities are set to receive to fund transportation across the board. Even if city governments direct all of their available funding to maintenance and preservation, that isn’t expected to be enough.

As the financial issues with the state transportation budget have taken center stage — a budget that had remained focused on system upgrades over basic maintenance to the state system — the issues funding local transportation needs are expected to be much more acute. And local governments have a much smaller universe of revenue options to tackle transportation, and many of those options are regressive, like sales taxes.

This analysis comes as PSRC prepares to refresh its Regional Transportation Plan on a regular four-year cycle, and policymakers will be faced with decisions on how to bridge that gap, at least on paper. The current plan, adopted in 2022, plugged a smaller hole with an ambitious new source of transportation revenue, a road usage charge (RUC). The RUC envisioned in the plan not only would charge drivers 5 cents for every mile they travel, making up for lost gas tax revenues as the transition to electric vehicles ramps up, but would double the charge during peak hours, essentially acting as a congestion pricing tool. The political viability of such a tool remains very much in doubt.

Meanwhile at the state legislature, a RUC pegged simply at an equivalent rate to the gas tax (2.7 cents per mile) has proven a non-starter, failing to advance since the 2022 session. The most recent road usage charge proposal, put forward by House transportation committee chair Jake Fey (D-27th, Tacoma), would have required any future revenues be restricted to “highway preservation and maintenance purposes” — apart from 10% surcharge intended to fund bicycle and pedestrian safety programs. That would help the state highway system, but not deteriorating local road networks or transit agencies that are badly in need of funding to expand service, getting cars off the road.

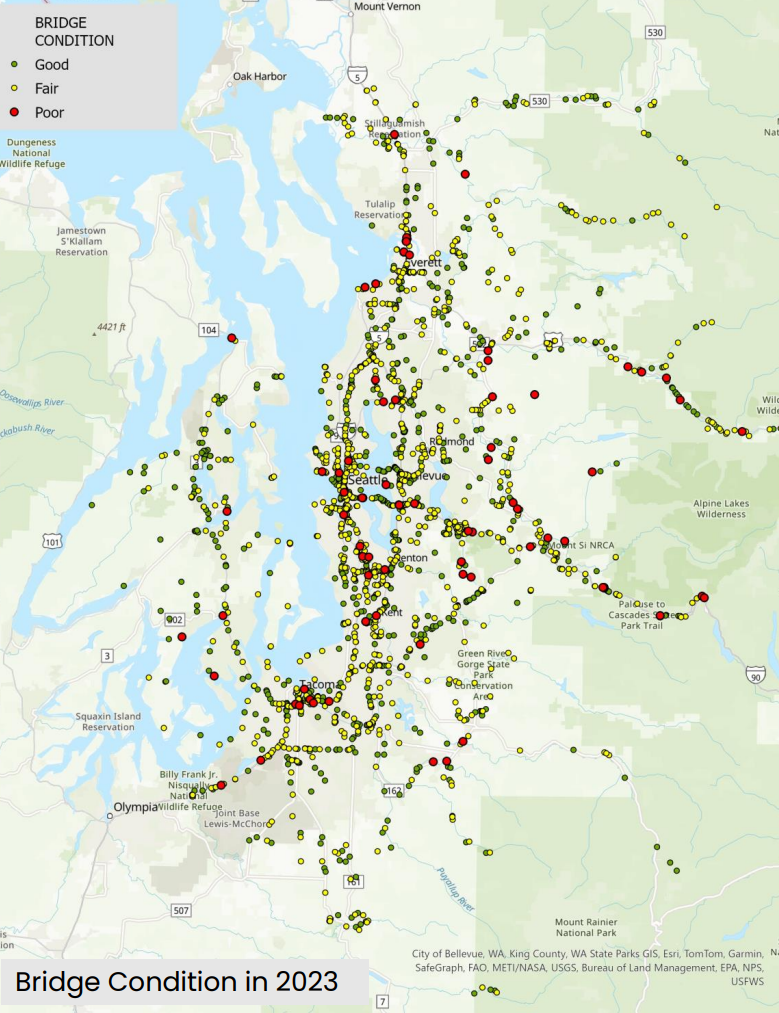

The scale of the maintenance crisis when it comes to local roadway networks only continues to snowball. From 2021 to 2025, the projected amount of funding that would be needed to bring every city and county road throughout the four county region up to a “satisfactory” condition increased by 50%, from $6.1 billion to $9.2 billion, in large part due to increases in labor and materials costs. Meanwhile, the condition of the region’s bridges continues to decline, with 88 bridges now rated “poor,” up from 69 in 2020. Around half of those bridges aren’t on the state highway system, but their repair costs are daunting for local governments.

Ultimately, the breakdown of the funding gap underscores the need for any new transportation revenue to be distributed more broadly across the transportation system. Out of the six cent gas tax increase approved by the legislature this spring, just 2.5% of the increased revenues are set to go to cities, with another 2.5% to counties — numbers that don’t seem to have much bearing on the actual anticipated needs for those segments of the transportation system.

Along with analyzing the gap, PSRC has started to look at some potential revenue options that could fill it. The road usage charge remains at the top of the list, with a gas-tax equivalent expected to bring in $15 billion for the region over 25 years. Allowing local transit agencies to increase the amount of sales tax revenue they’re able to collect also has the potential to raise additional revenue, but that funding would likely be concentrated in areas where voters are more likely to support transit ballot measures. As the breakdown shows, it’s not just about how much money comes in, but how you spend it.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.