Because of courageous students at Rainier Beach High School who started a petition that gathered 18,000 signatures in only a few days during the 2020 Black Lives Matter uprising, Seattle Public Schools removed police from campuses. That was a powerful step toward making schools safer for everyone.

But now, five years later, we’re still fighting for the same things: real safety for students — not more police in our schools. And the fight is urgent — because city leaders want to start by bringing cops back to Garfield High School.

People need to know the story of Mi’Chance Dunlap-Gittens, a Garfield student who should still be here. Mi’Chance was a senior who wanted to be a lawyer. He was out with a friend on the night of January 27, 2017, when plainclothes detectives sprang from the back of an unmarked van on a dark Des Moines street.

Not knowing who they were, Mi’Chance ran — and they shot him in the back of the head. He was just a kid. The officers were looking for someone else but mistook Mi’Chance for the person they were after.

Let’s be clear: the research overwhelmingly shows police don’t make schools safer.

Data shows that Black students made up just 15% of the U.S. student body in 2015–2016, but they accounted for 31% of school arrests.

A study by the Justice Policy Institute found that schools with police have five times more arrests for “disorderly conduct” — things that shouldn’t even involve the criminal system.

A Public Administration Review study found that while school resource officers (SROs) slightly reduce some forms of violence, they do not prevent gun-related incidents. Instead, SROs negative impact leads to more suspensions, expulsions, police referrals, and arrests — especially for Black students and students with disabilities.

We don’t need more cops in schools. We need more care.

Across Washington, we’ve seen students—especially Black, brown, disabled, and neurodivergent students — criminalized for being kids. The ACLU of Washington released a report that detailed the abuses of cops in schools: A 15-year-old was charged with felony assault for spraying fart spray in school. A high school student was referred by school police to the prosecuting attorney on suspected charges of assault in the fourth degree after the student poured chocolate milk on another student in the school lunchroom. A 12-year-old with disabilities was pinned to the ground and charged with felony assault for spitting.

If our leaders truly cared about student safety, they’d focus on what’s proven to work: more mental health counselors, safe spaces for students to take a break, and more funding for Black-led community groups, like Community Passageways and Choose 180.

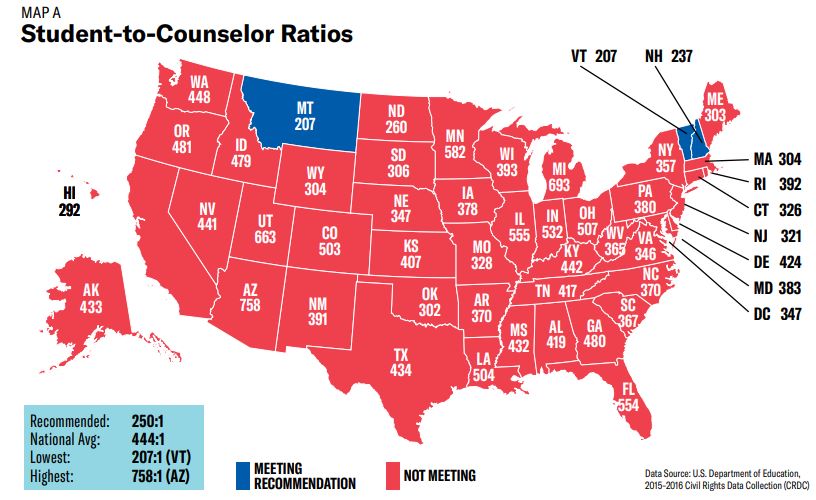

Too many schools are making the opposite choice. A 2019 ACLU report found that 1.7 million children in the U.S. attend a school where there is a police officer, but no counselor — and 14 million attend a school without a counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker, yet still have a cop.

Having studied this research after the tragic shooting at Ingraham High School, the Seattle Student Union led the fight to win $20 million from the City Council to help keep our schools safe by funding mental health counselors in every Seattle public high school. That was a huge victory, showing what’s possible when students organize and speak up.

But Mayor Harrell delayed the funding, and the City Council later cut it to $12.5 million. Many schools still don’t have the mental health support we need. At Nathan Hale, there’s only one part-time counselor, and they’re overwhelmed. At The Center School, where over 70% of students are LGBTQ+, there’s no counselor at all.

“It hurt,” Ingraham senior Cici Kennedy told KUOW, “It just kind of felt like we were devaluing mental health support in general and not giving it the attention that it should be given in terms of money. It’s just not enough.”

We demand real student voice in these decisions. Too often, adults cherry-pick students who agree with them instead of listening to the majority of us. We’ve been calling for a citywide student policy roundtable so students have a real seat at the table.

The truth is, we don’t go to school to be watched, criminalized and punished. We go to school to learn, grow and build a future. We need our city and the school district to keep its promise: invest in counselors, not cops.

As we continue this struggle, we’ll be launching a student survey to gather more perspectives across Seattle. If you care about real safety—not just the illusion of it — join us. Together, we can build schools where every student feels safe, supported, and free to thrive.

Russell McQuarrie-Means and Miles Hagopian contributed to this article. McQuarrie-Means and Miles Hagopian are local public school students and activists, along with fellow authors Leo Falit-Baiamonte, Liya Bogale, and Fatra Hussein.