Multiple whistleblowers have raised the alarm, but the Office of Inspector General still appears to be falling short of its charter and legal responsibilities.

Seattle Inspector General Lisa Judge appears to have been withholding, altering, and destroying public records as a matter of routine practice, based on an investigation by The Urbanist tying a former employee’s account to public records obtained from the office. Some of this appears to have been done in an effort to cover up information that may have been publicly perceived as scandalous or otherwise embarrassing to the Seattle Office of Inspector General (OIG), the Office of Police Accountability, and the broader Harrell Administration.

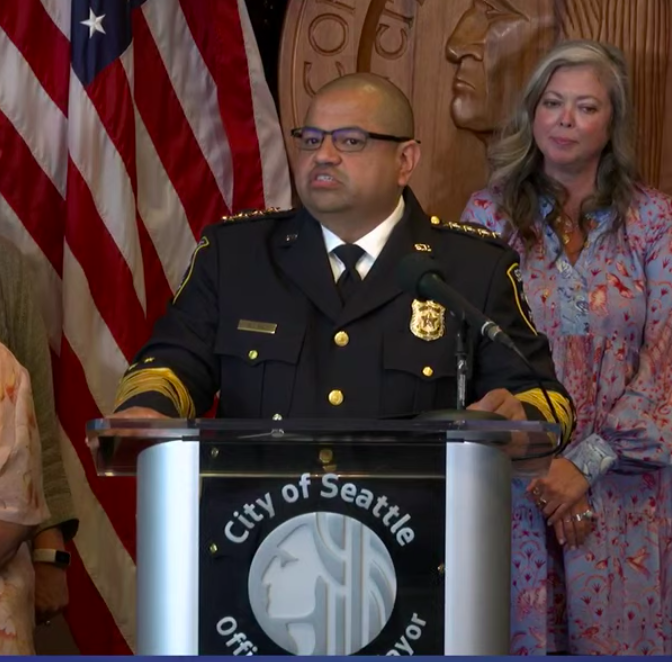

Officials that Judge allegedly sought to shield included former Office of Police Accountability (OPA) Director Andrew Myerberg, who was promoted to Mayor Bruce Harrell’s cabinet in 2022. OIG also appears to have interfered in the investigation into whether former Seattle Police Department (SPD) Chief Adrian Diaz had an affair with his Chief of Staff, Jamie Tompkins, withholding relevant handwriting samples.

Late last year, Judge fired Lacey Gray, the OIG’s former records manager, in what appears to have been retaliation for whistleblowing on the office’s improper disclosure of records in the Diaz case. The state ultimately sided with Gray, stating that she was terminated without cause, and awarding her full unemployment benefits.

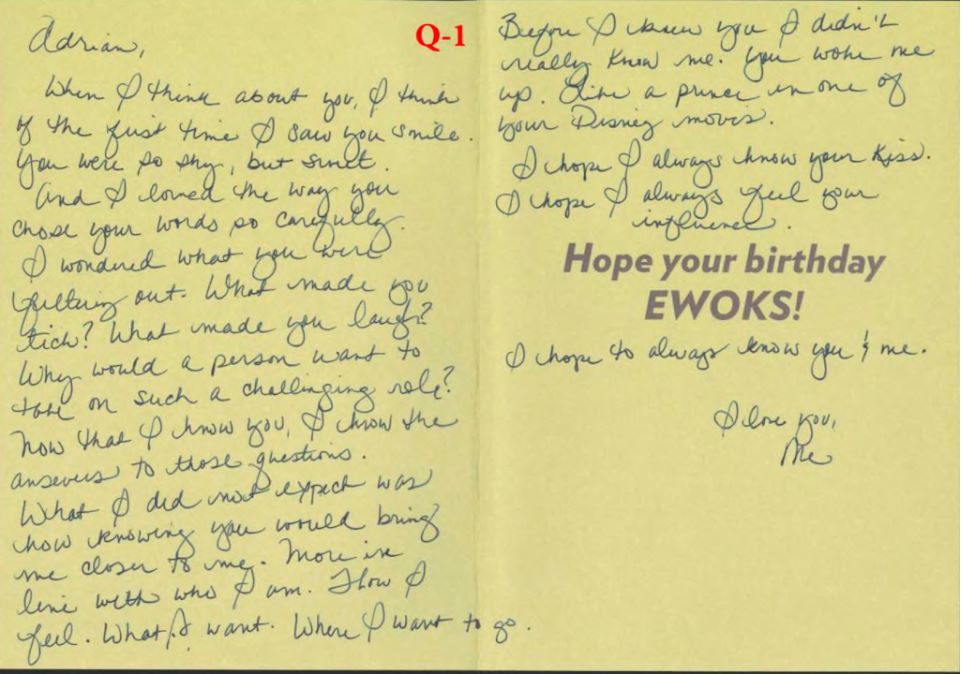

After initially defending Diaz, Mayor Bruce Harrell fired him in December, saying that Diaz had lied to him about his relationship with Tompkins. Harrell’s case rested in part on the alleged love note and the handwriting analysis based on incomplete samples that tied it to Tompkins.

The OIG is one of the City’s three police accountability bodies created by federal mandate in the 2012 consent decree. According to the OIG’s website, the office is supposed to oversee the management, practices, and policies of SPD and the OPA.

Like the OPA, the OIG has come under increasing scrutiny, following the City’s accountability system’s response to police treatment of protestors in 2020, and this is not the first time Judge appears to have run afoul of records laws. In 2021, OIG and Judge were the subjects of an ethics complaint, which included allegations of violations of Washington’s records law.

The City dismissed the complaint, claiming it did not meet ethics standards. Further reporting subsequently confirmed key issues flagged within the ethics complaint. Overtly, the City did not do anything to address the records issues the ethics complaint highlighted, except create a new records position — the one that ended up being Gray’s.

OIG did not return emailed requests for comment before publication.

Attempts to hide records from public

Based on records and information the Urbanist obtained, it appears that Judge also sought to structure investigations to obscure sensitive records.

Following The Urbanist’s article on the buried investigation into current director of public safety Andrew Myerberg, the publication has learned that Judge initially allegedly wanted the investigation to go through the Seattle City Attorney’s Office (CAO) as a middleman. It appears that Judge believed she could claim to any requestors that the records were exempt under attorney-client privilege.

“Lisa thought that she could, if they had it under the control of the city attorneys, claim attorney-client privilege on the majority of the records,” said former OIG records manager Lacey Gray. “Even though the third party was an attorney, they weren’t conducting attorney-client work, they were conducting a misconduct investigation, which is different and doesn’t fall under the attorney-client privilege exemption.”

Additionally, Judge believed that because it was an open investigation, the office could withhold the records, Gray said, adding that “that’s just false. They can’t.”

Gray was hired in 2022. Her position was funded by a Seattle City Council decision to allocate funds to OIG specifically to hire a trained records manager, following the revelation in a different whistleblower complaint against OIG that Judge and her office were improperly handling records. As a public disclosure officer, Gray has extensive training in records law, and checked certain issues she encountered within OIG with the City’s Law department.

Gray said in January that believes that her November firing was due to the fact that she blew the whistle on Judge and Perez Morrison for improperly releasing records in the Diaz case. (More on that to come.)

The state awarded Gray full unemployment benefits for being terminated without cause. Gray is suing the City of Seattle for unlawful termination for an unspecified amount, though her tort claim was for $5 million. Her case is slated to go to trial in May 2026.

Gray said that she handled the first public disclosure requests in that case, and had to start pushing back against illegal records practices from the jump.

After Judge initially directed her and other records staff to deny the records in the Myerberg investigation outright, because the records concerned an open investigation, Gray said that she had to explain to Judge that she could not do that, because the investigation wasn’t a criminal one. Gray subsequently learned that, until her arrival, the office had been withholding investigation records, regardless of whether they were legally allowed to do so.

“Prior to me starting, OIG had been blanket denying open cases, withholding documents, so they had been doing things illegally up until when I arrived,” Gray said. “And so I said, ‘Nope, you can’t do that.’ And then I cited the law.”

“I had a meeting with [Judge], and she was not happy about it,” Gray continued. “She … insisted there should be an HR [Human Resources] exemption, that there had to be an HR exemption, she was positive there was an HR exemption.”

Notably, the office did not appear to have the same personnel issue qualms when it came to releasing records in the investigation into former Chief Diaz.

Judge eventually directed Gray to “hold back anything of value [in the Myerberg investigation records], until the very, very end so that [the requestor] didn’t have it,” Gray said.

“When leadership directs that, it’s because they’re hoping that the requestor is going to get tired of the request — that they’re going to stop paying for it, abandon it, that sort of thing,” Gray explained. “So the idea by leadership in the city is give them the garbage, up until the very last — like ‘til you get pressed to the end and then start giving them stuff.”

Gray said that she approached Aaron Valla in the City Attorney’s Office (CAO) about Judge’s directives, because of the legal mess they posed to the office. Valla, who heads the CAO’s records and public disclosure unit, told Gray to “document everything to protect myself,” which Gray did.

Hiding and destroying records

Gray alleged that Judge specifically directed her and other OIG staff to keep records from the public, or feed the public a long stream of “garbage” records, if the records in question would make the office or the City look bad.

The practice of giving relatively useless records in the specific records request regarding the investigation into Myerberg was in order to appease Mayor Bruce Harrell, Gray said. Myerberg had by then begun to work in Harrell’s cabinet, after departing his role leading the Office of Police Accountability (OPA).

Both Gray’s allegation of OPA appeasement and Judge’s records mishandling are reflected in the whistleblower complaint lodged against OIG in 2021.

“She’ll find any way to withhold the record,” Gray said. “So, if there’s a record that she doesn’t want to go out, then she would] come to me and tell me that it can’t go out; that it is exempt. And maybe she’ll give me a reason, and maybe she won’t.”

Gray alleged that when she pushed back and told Judge that they could not withhold records without a reason — that it was illegal — Judge directed her to “find one… figure it out.”

An email the Urbanist has obtained reflects this. In the email, Gray had written a summary regarding a prior meeting about a specific public disclosure request. The email was addressed to several senior OIG staff members, including Judge.

“Lisa – will review the PRA to see if there are any exemptions that may relate to this situation other than the one LAW provided regarding criminal investigations,” Gray wrote.

“Thanks Lacey, this is really helpful,” Judge wrote back. “I think the only tweak I have is the last line about opinions about PRA interpretation. Those will come to ELT to be vetted and refined before reaching out to law for any needed advice.”

Gray also said that, sometimes, if it came to a record that only Judge had, Judge would tell her it didn’t exist anymore — that it was destroyed or she allegedly could not find it.

Unless the record is one that is defined as “transitory,” meaning that they have short-term, temporary informational use, the majority of records within OIG have to be retained for 5-10 years, or sometimes permanently, depending on the kind of record.

Destroying records before the allotted timespan has elapsed is illegal in the state of Washington, and is considered a Class C felony. The OIG has only been in existence since 2018, which means that, during Gray’s employment, no record would have reached this required age. Penalties for records destruction include imprisonment for up to five years, a fine of up to $1,000, or both.

This was a major problem, Gray said, not just from a PRA standpoint, but from a City legal operations standpoint. Attorneys in the City Attorney’s Office do not have access to OIG files, and therefore have to reach out to OIG for OIG-specific information they might need. But if that information is missing, then City attorneys may not have crucial information. Therefore, the practice of destroying records in such cases could result in allegations of case mismanagement, in addition to PRA suits against the City of Seattle.

One example can be found in a public records request the OIG received in 2022. The request was for phone records from different OIG employees, including Judge.

However, Gray said, Judge refused to give over her phone records so that Gray could retrieve the requested data. The information the requestor sought was on Judge’s old phone, Gray said, and Judge had recently upgraded her phone. Gray said that she was concerned, because at the time of the request, another City department was facing a PRA-based legal challenge regarding the same requested information.

At first, Gray said, Judge claimed that she could not find her phone. When Gray pushed, Judge said she had it, but could not remember the password. When Gray asked if she could have the phone to attempt to retrieve the password with Apple (Judge’s phone was an iPhone), Judge said she remembered the password after all, but that the majority of texts had been deleted.

The PRA states that the practice of deleting texts and not backing them up is illegal.

Gray alleged that Judge would also regularly direct staff to destroy drafts of investigations and reports. While it is legal under state law not to retain drafts if the information changed is negligible, such as a comma here or a period there, drafts that reflect internal discussion or the progress of significant policy changes, for instance, must be kept, so that the public can see how such things came to be.

The deletions that Judge allegedly directed OIG staff to make often represented significant changes, Gray said. Contrary to Judge’s directives, Gray told staff she trained not to delete drafts.

“That pissed [Judge] off — that angered her,” Gray said. “I had a conversation with her about it because she did not want that to be the directive to staff and that I was wrong. She told me that I was manipulating the public by directing staff to do this.”

Gray recalled that Judge accused her of “picking and choosing” the drafts they saw. Gray pushed back, saying that she was following the law, which dictates very specific records retention rules.

Even after this, Judge still allegedly directed staff to delete the records, and did the same herself. Gray estimated that about half the staff followed Judge’s orders, because they were scared of her, but they were also scared of violating the law.

Furthermore, Judge directed her and other public disclosure staff to stop passing public records request installments by the City’s Law department, Gray said. Public disclosure staff pass such records by Law to ensure that they are complying with the state’s Public Records Act.

The Urbanist obtained several records reflecting the in-office directives to keep certain information from the public.

Gray said on July 18, 2023, Judge directed OIG staff to stop asking for outside legal opinions altogether since “[Judge] has 20 years experience in police records as an attorney in Arizona and she knows everything there is to know.”

“So, it is my understanding that I am not allowed to contact Law for advisement on the PRA any longer,” Gray said. “I was told to go to [Judge] and Bessie for any interpretation questions on the PRA.”

About a year later, former OIG Deputy Director Bessie Scott wrote to Judge and Gray, regarding what appears to have been Judge’s proposal for a confidential folder, where allegedly PDR-exempt material would be kept.

“My recommendation aligns with Lisa’s in that there should be a Confidential folder that has information which is sensitive and exempt for PDR requests,” Scott wrote in a July 3, 2024 email.

The email does not include the Law department, and does not mention compliance with state law.

An email from August 13, 2024 shows that Gray set up that folder, per Judge’s instructions. According to Judge’s instructions, only Judge, Perez Morrison, and OIG employee Tiffany Preston had access to that folder.

The Urbanist also obtained a July 2023 email thread showing that someone told Scott that Gray had asked the City’s Law department a question about particular records requests involving then-open investigations.

In the email, Scott asked Gray why she went to Law since Judge had stated what she wanted withheld in a records request. The email appears to imply that Gray should not have gone to Law, despite it being part of Gray’s job to ensure that exemptions and redactions are applied properly.

“My understanding is that Lisa has made a determination as to what can be released based on the fact that certain cases are not closed and there are no DCMs. What are the issues that are requiring this office to go to Law?” Scott asked in the July 10, 2023, email, before asking Gray to set up a meeting with her, Judge and OIG investigations supervisor Mattias Gyde for the following week about the issue.

Gray told Scott in an email the following day that, generally speaking, when she reaches out to the Law department or to Seattle’s Citywide Public Records Act (CPRA) Program — which falls under the City’s Information Technology (IT) department — “it is to request assistance on language for responding to requestors or confirmation of my understanding of exemptions allowed under the PRA.”

“It is always my intention to mitigate risk for both OIG and the City, and to remain consistent when I respond to requestors both internally and City-wide. Departments often receive duplicate requests across the City, and we especially share similar requests with SPD, who currently responds to requests for OPA,” Gray wrote. “I do also reach out to Tara [Collings] at SPD on occasion, to discuss those duplicate PDR’s and for any questions I may have about appropriate exemptions for SPD records.”

“To date,” Gray continued, “I have not received any direct, written guidance from OIG leadership regarding how to handle requests for open cases and look forward to receiving this next week. At that time, I will be happy to share with you the guidance I have received from LAW/CPRA on this topic and how SPD responds to open OPA requests.”

In a subsequent email, Scott reprimanded Gray for not clearing it with her superiors before reaching out to Law, and for Gray’s tone and word choices in her overtures to Law.

Excluding evidence

In addition to withholding records from the public, without OK’ing it with Law, OIG appears to have recently withheld evidence in an investigation into whether former Seattle Police Department (SPD) Chief Adrian Diaz had an affair with former SPD Chief of Staff Jamie Tompkins. This happened after Judge fired Gray from OIG on Nov. 8, 2024.

The independent investigator the City of Seattle hired for the case ultimately determined that Tompkins wrote the now-infamous Ewok card at the center of the investigation, based on handwriting samples Tompkins disputes were hers.

Tompkins has filed a tort claim with the City of Seattle for $3 million, and had her mediation meeting with the City on June 25.

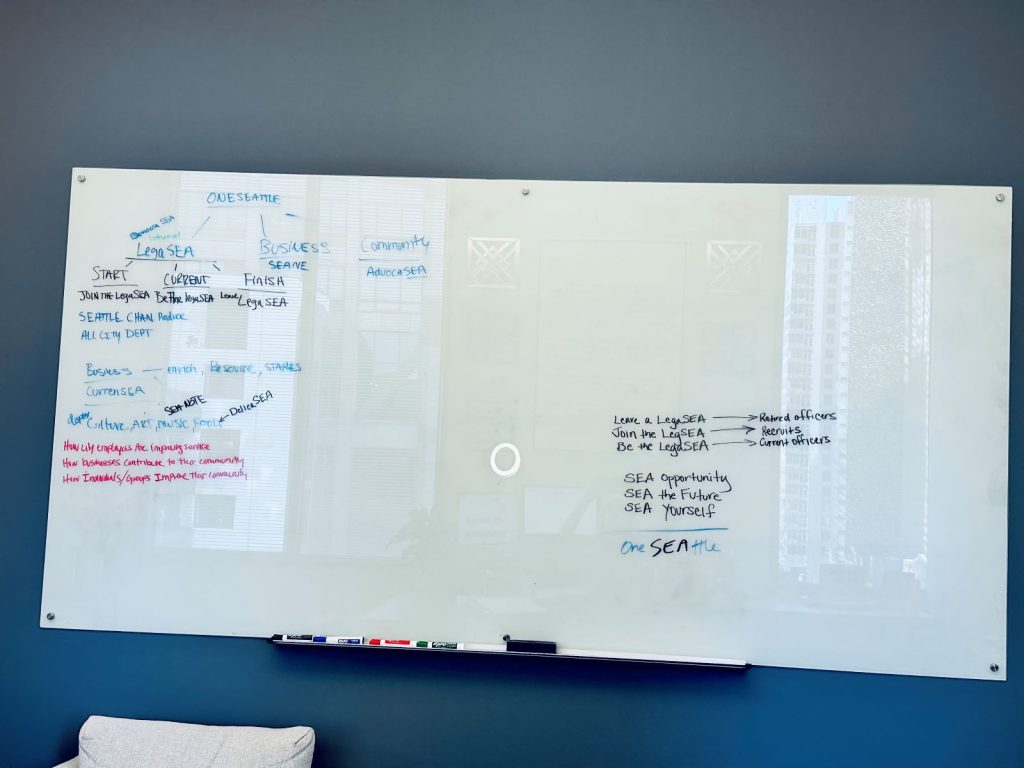

In an official memo, Gyde wrote that on November 26, 2024 he and Deputy Inspector General Alyssa Perez Morrison gathered from Tompkins’ office “two notebooks containing some handwriting, three file folders with handwriting on them, one packet of papers stapled together titled “In Pursuit” with handwriting on the title page, and photographs of writing on the whiteboards in the office.”

Gyde determined that “there appeared to be different styles of handwriting found in various locations around the room and to our understanding, the office had already been cleaned out by an SPD administrative assistant. None of the exemplars found were signed or otherwise directly identifiable as Ms. Tompkins’.”

Gyde does not state how he and Perez Morrison determined or knew that none of the remaining samples were identifiable as Tompkins’ handwriting, but they did exclude them from the handwriting analysis, nonetheless.

Neither Gyde or Perez Morrison — or anyone else within OIG — appears to be a trained handwriting specialist, or had a handwriting specialist definitively rule out the handwriting as not belonging to Tompkins.

No one from OIG or SPD returned requests for comment, but Tompkins told The Urbanist that the notebooks and handwriting on the file folders, packet, and whiteboard would likely have been hers.

Tompkins, who quit her job with SPD on November 6, 2024, said that the handwriting should have still been on the whiteboard, at the time of evidence collection less than three weeks later.

“My big white board had the handwriting of myself and three male employees. One officer and two civilians,” Tompkins said, “We all had a brainstorming session and we wrote it in front of each other. It was an idea I had to expand the ‘One Seattle’ slogan into a campaign.”

The metadata of the image Tompkins provided to The Urbanist shows that the picture was taken on August 14, 2024. The slogan-writing effort was in preparation for a police recruitment video advertisement, as an expansion of Mayor Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle campaign.

Some of the portion of writing on the board that Tompkins said is hers also appears in an SPD One Seattle video, where Tompkins herself provides the ending voiceover.

“SEA the opportunities, SEA the future, SEA yourself,” Tompkins’ voice says in the August 9, 2024, video, exactly as is written on the whiteboard.

An SPD employee confirmed that, after Tompkins quit, to the best of their knowledge, no one went into the office and changed anything on the whiteboard, and the last time this employee went into Tompkins’ office to talk with her, the handwriting on the board was Tompkins’.

This employee also told The Urbanist that, sometime in early 2025, SPD Officer Tay Gray-Mcvey and Officer Andre Sinn moved into Tompkins’ office.

Gray-Mcvey is one of the officers whom Tompkins said sexually harassed her, and did so to a particularly intense degree. Tompkins said in her demand letter to the City of Seattle that Gray-Mcvey once told her he could always find her, because he could “track her scent.”

No-show habits

Gray recalled a specific meeting wherein she and Judge discussed that releasing records about the investigation into Myerberg to the requestor was required by law. She said that the meeting was memorable not just for the content — Judge was unable to come up with an HR exemption — but for the fact that Judge showed up to it.

“Lisa regularly no-shows to meetings,” Gray said. She estimated that in her two-and-a-half years of working at OIG, Judge showed up to “maybe” two of her meetings on time. “Otherwise, I was no-showed to every meeting — and most meetings she no-showed and didn’t bother sending an email or text or [Microsoft] Teams chat to say anything before or after, or even acknowledge that she missed the meeting. So that was pretty par for the course. It wasn’t just me.”

Gray said that Judge did this with “every single staff member and people outside the organization,” and that it was Judge’s assistant’s job to make regular excuses regarding Judge’s absence.

This no-show behavior appears to line up with the records The Urbanist unearthed, regarding Judge’s parking practices and attendance records.

Gray said that it was this usual no-show behavior that compelled her to take an important meeting that Gray’s supervisor, Rhonda Lyons, said Judge had scheduled, regarding records in the Myerberg investigation. Gray felt compelled to take the meeting, even though she had scheduled to be out of work that day for a personal appointment. Gray recalled sitting in her car in the parking lot of the building in which her personal appointment was to take place.

In the meeting, Gray said that Judge appeared to come to terms with the fact that the requestor had a right to the records.

But, Gray said, “it was almost like that previous stuff never happened, because then [Judge] was just like, ‘Okay, well just give the requester the garbage — the emails, setting up of meetings and appointments and interviews, but don’t give the interviews — basically, the back and forth, running everything through the attorney, but don’t give the interrogatories.’”

“Don’t give … anything of value, in essence, is what I was directed to do,” Gray said. “And she said, ‘I want to see everything that you’re sending out now.’ [The Myerberg investigation records were] one of the only ones that she wanted to see.”

With the exception of those records and a handful of others, Gray said that the OIG public disclosure team was left to coordinate on their own, when it came to records. This meant that she and OIG records staff were usually able to meet projected deadlines and goals.

But with the records that Judge specifically wanted to oversee, Gray said that they tended to get delayed, because of Judge’s habit of skipping meetings.

“It was very frustrating, particularly because with the PDR law, you’re required to hit these deadlines, to keep them — you’re required by law to do it,” Gray said. “And that made my job all the harder.”

Gray said that she could not recall exactly which records Judge directed Gray to pass by her before review, but that Judge decided whether she needed to review, based on content of records requests.

Judge directed Gray to send her a link for any records she wanted to oversee. Judge specifically wanted a link, Gray said, “so there [were] less records and the link could be deleted.”

But even when Gray would send the requested link, ask Judge to review the records by a certain date up to three weeks out, and send reminders, the deadline for the records would sail right on by, she said.

“And I would have to decide, am I going to risk making her mad and give the installment, or do I push [the installment date] back?” Gray said. “And I don’t remember, I think I probably did push installments back, but I also then got really frustrated, and then [Lyons] would just then direct me to just put them out — if [Judge] was given every opportunity and enough time to review them and she’s just not doing it, after so many times of her not my directive from [Lyons] was just go ahead and send the installments out.”

The Urbanist has obtained email records corroborating Gray’s account.

Altering records

Gray said that Judge also directed her and other OIG staff to alter public records, after the records request was made to the office and before sending them out. This is illegal.

In a July 19, 2023 note, Gray wrote that a screenshot she had taken of a Microsoft Teams chat with Gyde “were ok to go out except that she wanted Matthias to review and go through and change one of them. Edit, correct, etc.”

“This isn’t the first time she has asked this of Matthias,” Gray wrote. “She has also asked me to add or remove records that she thinks will make us look better or bad, give something context or take something away. But those are just verbal requests and never in writing.”

Gray included the screenshot of the Teams chats in her notes. The chat bears a June 29, 2023, date stamp.

“Hey, has Lisa talked to you about those records for the union request?” Gray asked Gyde over chat. “She said that the records were fine to give, but that there was one she wanted to do something with.”

“Nope,” Gyde replied. “Haven’t heard a thing.”

“She said there was one with not full sentences and stuff,” Gray said. “Just wanted it to look better.”

“I can probably fix that,” Gyde said. “Are the docs in the folder on the G[:Drive]?”

Gray explained that she asked him over Teams chat like this, because she wanted it documented on-record in a “less obvious way” that Judge had directed staff to alter records.

“I didn’t want to come right out and be like, ‘Hey, Lisa directed you to violate the law,” Gray said. “I was trying to be unobvious and not raise any flags about it being memorialized.”

Additionally, Gray’s 2023 notes claimed that Judge would sometimes also ask her to send extra, unrequested information in public disclosure requests, in order to make the requested record “look better.”

“An example of this is when someone requested just an ROI [Report of Investigation] on an OPA case, she wanted me to send other records along with it, because it helped make it look better and used the excuse it provided context to the requestor,” Gray wrote. “But that it [sic] is not my job, to find other records to provide context or make something look better, when a request comes in.”

Activities like those within OIG are the kind that undermine transparency and worry accountability advocates. One such advocacy group, WashCOG, is a Washington-based coalition that advocates for governmental transparency and public access to government records, a right granted by law.

When the Urbanist described the allegations against OIG, WashCOG’s secretary, George Erb, expressed concern.

“Seattle’s Office of Inspector General for Public Safety especially needs to operate lawfully and beyond reproach because [the office] was founded to ensure ‘the fairness and integrity of the police system’ — a vital objective,” he said. “Failing to live up to the highest standards jeopardizes the OIG’s own credibility and the public’s trust in its work.”

“Every local government has a duty to follow Washington state law, including the Public Records Act,” Erb continued. “That particular law has been on the books for more than 50 years.”