Parking reform has become a national movement. Shoreline joined the trend to boost homebuilding and green mobility.

On August 11, the Shoreline City Council eliminated car parking mandates and revised bicycle requirements for new developments in Shoreline. Proponents say the change will spur new housing construction, lower housing costs, reduce car dependency, and encourage greener modes of transportation.

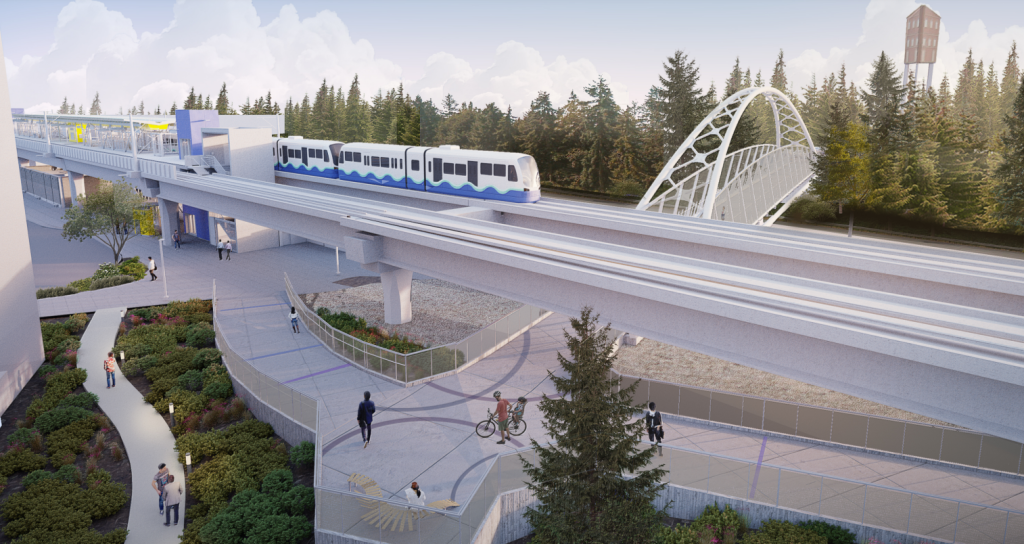

Rather than restrictive, government-issued per-unit requirements, Shoreline builders can now determine how much car parking is appropriate for new development projects. The City has also expanded bike parking standards for new construction. The legislation follows the opening of two light rail stations and a bus network overhaul that boosted frequency. The idea is that improving transportation options will allow Shoreline residents to reduce reliance on cars and make better use of space near new transit investments.

Allison Luzader is a Shoreline resident who submitted public comment in favor of the parking reform at the August 4 City Council meeting. Luzader moved to Shoreline from Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood, where she says she walked most places and traveling by foot was much more accessible. She wishes the neighborhoods in Shoreline were more walkable and had more amenities.

“It’s something that I think can really pave the way for more housing to be built in the area,” Luzader said.

In 2023, the Washington State Legislature required that cities reform single family zoning via House Bill 1110 and HB 1337, seeking to respond to the housing crisis. This spring, the Legislature followed up with statewide parking reform to encourage the development of “middle housing.” Senate Bill 5184 requires that cities reduce their parking mandates on builders. Some cities have opted to go beyond that minimum standard and eliminate parking mandates altogether.

Approximately half of Washingtonians spend 30% of their income on housing costs, with a quarter of residents paying 50%, according to a report published by the University of Washington.

A report by the Sightline Institute, a non-partisan environmental think tank, estimates that a parking space costs between $5,000 and $60,000 to build, thereby significantly increasing the cost of housing. Mike Appleby, vice president of Chicago Title Insurance, estimates the maximums are even higher for underground parking. Chicago Title Insurance is a real estate services firm with extensive operations in the Seattle region.

“We need to come up with a product that someone doesn’t have to spend a million dollars to be a homeowner,” Appleby said.

The ordinance eliminates all parking minimum requirements for buildings in Shoreline. Any house, apartment, business, and new building in Shoreline can forego pavement for motor vehicles. However, this does not mean developments cannot supply parking. If a developer chooses to provide parking, they must follow all pre-existing design requirements.

Sightline Institute reported that one in four homeowners in Washington has zero to one car, yet 91 jurisdictions in Washington require two or more off-street parking spaces per housing unit.

Shoreline City Councilmember Keith Scully has participated in the parking discussion for 15 years, as both a city council member and a former member of the Planning Commission. He says Shoreline will still be recognizably Shoreline, especially since the ordinance does not affect pre-existing parking. However, it allows builders to follow market demand, whether that be through parking lots or development near bus stops.

“Developers have to sell or rent what they build, and so they are much more market-driven than they are regulation-driven,” Scully said. “Most of the big ones aren’t really going to be that different, just because, if you’ve got 300 units and no parking, that’s not an attractive place to rent or lease.”

Scully was initially hesitant about the plan to eliminate required parking, but found through his work with the Planning Commission and City Council that something had to give for Shoreline to grow.

“Watching our attempts to bring urban density to Shoreline, particularly around high-capacity transit, and trying to figure out how we can do that while still preserving open space and parks and a diversity of businesses, and realizing that you can’t have everything,” Scully said. “So the evolution was just realizing that parking is going to have to be the thing to go, and then doing our best to design these new high-density places so that you don’t need parking.”

The ordinance now requires builders to allocate space for short-term and long-term bike parking. Short-term parking spots are standard bike racks for visitors, whereas long-term bike parking spots are enclosed lockers to protect from theft, vandalism, and weather.

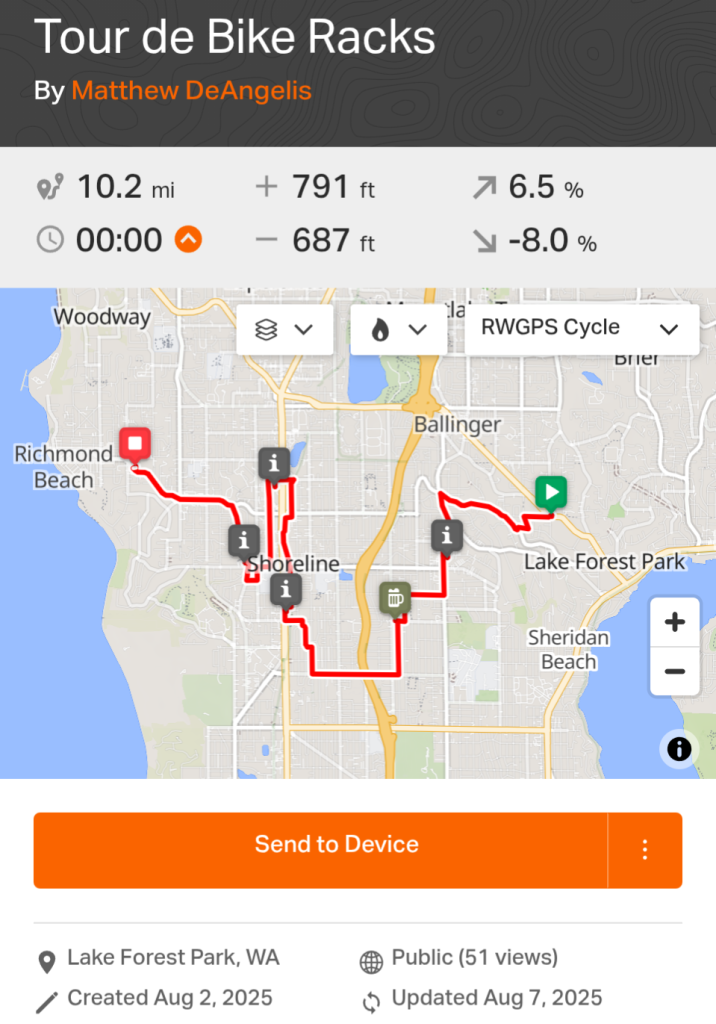

As for pre-existing buildings, Scully would eventually like the city to develop grant programs to build bike racks. Until then, nonprofits such as Urbanist Shoreline are working to supply bike racks, with seven racks currently installed from Lake Forrest Park to Richmond Beach.

The required bike parking goes hand in hand with Shoreline’s Bicycle Plan and the Transportation Element of its recently passed Comprehensive Plan update. The Bicycle Plan is intended to provide connecting routes for cyclists of all skill levels, from families with young children to cycling commuters.

Scully says gaps in routes, such as on the Interurban Trail, are what stop less secure cyclists from biking as a main mode of transportation based on public testimony.

Luzader echoed this sentiment.

“If I go to the grocery store, like to the QFC at 145th,” Luzader said. “I would not be excited to bike down 145th.”

Of those who are unable to bike, Appleby says billions of dollars are being allocated to public transportation.

“This is one piece of a really big process to make sure that the density we’re allowing works,” Appleby said.

Scully predicts there will be unforeseen issues that arise with the elimination of parking minimums, but believes those can and will be managed as they come up.

Public comments opposing the ordinance cited concerns about giving developers too much power to shape our communities. Opponents of the measure were outnumbered by supporters.

Appleby pushed back on the “evil developer” trope, saying that builders often live in the communities they work in.

“Homebuilders, developers, most live in this community already and in the area; they’re not doing something that is not thoughtful,” Appleby said.

Other public comments referred to urban density leading to more crime and increased hazards due to increased street parking. Logan Schmidt, King County Government Affairs Coordinator with the Master Builders Association, says with population growth and city density, there will be more of everything. However, without parking restrictions, more housing can be built to create safer communities.

“If people can safely live in homes in the communities where they work, where they have family, etc., that creates safer, healthier, thriving communities,” Schmidt said.

Shoreline Mayor Chris Roberts says the city will still be responsible for maintaining parking. He says research on parking and parking reform in other cities supports the elimination of parking minimums.

“The areas in Seattle that have no parking minimums, I believe that most developers are still putting in parking and as a city,” Roberts said. “This is not a new concept, and it’s been a lot of research that’s been done across the nation on the effects of parking and how required parking adds to the costs.”

The Parking Reform Network provides a national map of cities that have adopted parking reforms. According to a study published in Transportation Policy journal, parking reform in Boulder, Colorado, has allowed investment into alternative modes of transportation and reduced automobile travel. Shoreline’s neighboring city of Seattle has already saved $537 million through parking reform.

Appleby says cities should refer to other cities that have produced successful models of development and parking reform but also believes collaboration between all parties is integral to meeting the needs of individual communities.

“That collaboration versus top-down thinking ‘just do it like this’ always seems to be the best option,” Appleby said. “Communities that do that end up with something that works really well.”