As the Seattle City Council entered the home stretch on deliberations on the city’s 20-year growth plan last week, members of the Seattle School Board weighed in, pushing the City to go farther to allow more housing. Acting in their personal capacities, a majority of Seattle Public Schools (SPS) Board of Directors signed onto a letter urging the city council to adopt an amendment from Alexis Mercedes Rinck expanding the number of neighborhood growth centers. They pointed to the pivotal link between the City’s restrictive land use decisions and the imperiled health of its public schools.

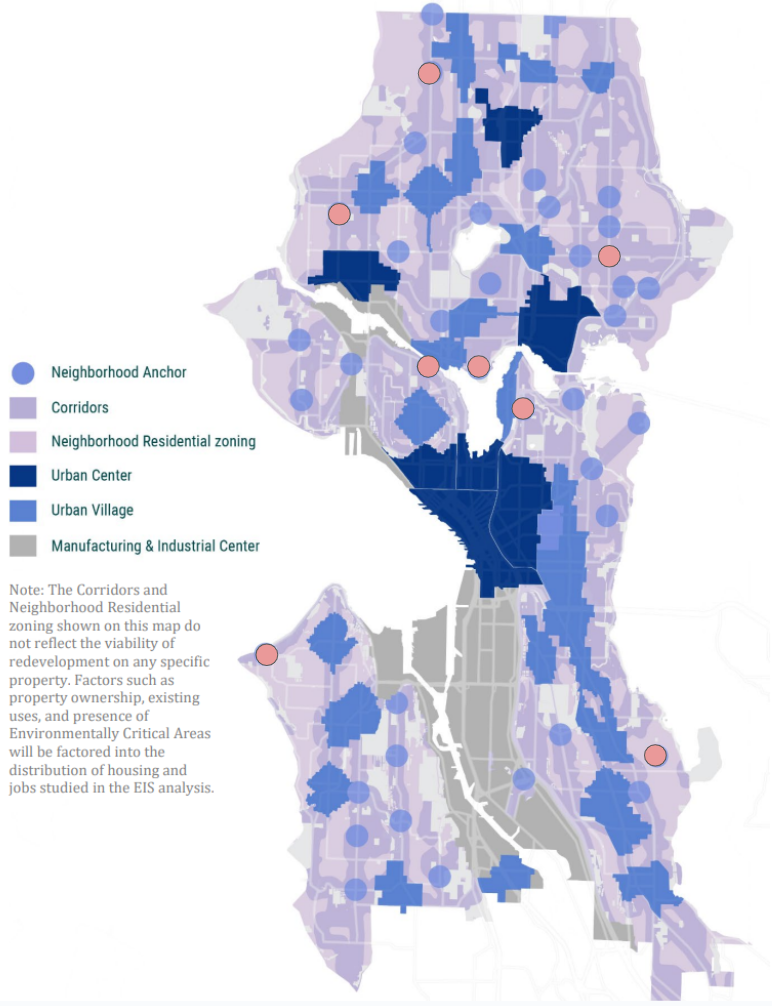

Rinck’s Amendment 34 would have restored eight separate “Neighborhood Centers” that had been dropped from consideration earlier in the plan’s development. Neighborhood centers are areas of increased housing capacity and expanded commercial zoning that are intended to foster more walkability and community amenities. Drawing the boundaries within Broadview, South Wedgwood, Loyal Heights, Gasworks, Nickerson, Roanoke, Seward Park, and Alki would have set the stage for zoning changes early next year. Those zoning changes are what finally clears the way for builders to start moving larger projects forward.

Amendment 34 was ultimately rejected, amid concerns that adding the centers back to the plan would require additional environmental review that could open the city up to a legal challenge. Instead, the council will consider the eight neighborhood centers next year as part of the annual process to update the Comprehensive Plan.

School Board Directors Joe Mizrahi and Liza Rankin and Board President Gina Topp had signed onto the letter ahead of last week’s board meeting, with Directors Evan Briggs and Sarah Clark adding their names during the meeting to comply with open meetings requirements. With that, a majority of the seven-member Seattle School Board went on record in favor of Amendment 34, albeit not acting officially as the school board as a body. SPS posted the letter to the board’s website.

Seattle’s school district faces significant challenges in the years ahead stemming from a long-term structural deficit, tied to declining enrollment and insufficient state support for public schools. After Superintendent Brent Jones put forward a proposal last fall to close up to two dozen schools around the district, community opposition was swift and fervent. Ultimately, Jones reduced the list to four schools before withdrawing it altogether. Jones has since retired, with the search for a new Superintendent now dragging on longer than expected.

“Councilmember Rinck’s amendments would help address our enrollment and budget challenges by adding more mixed-use, family-friendly housing near existing schools and transit,” the letter states. “These changes are needed and urgent. Many of these proposed neighborhood centers have significant overlap with school buildings that are currently under-enrolled and even schools that were considered for closure last year. Building more affordable homes near schools strengthens neighborhoods, reduces displacement, and will be a big step in ensuring every child in Seattle can attend a well-funded school close to home.”

“Seattle Public Schools has faced a 15% enrollment decline over the past decade. This decline leads to significant impacts to staffing, programming, services and school budgets,” the letter continues. “The District’s 2025 Enrollment Study […] confirmed that this decline is directly linked to housing affordability and family displacement. The study also found that neighborhoods with greater housing density and affordability have seen far less enrollment loss. Conversely low-density neighborhoods with rising housing costs have experienced the steepest enrollment declines.”

Mizrahi, who was appointed to the school board early last year and faces an election to be retained this fall, has emerged as a consistent voice for increasing housing capacity to sustain local schools, and earlier this summer testified in favor of capping King County’s school impact fees for multifamily development.

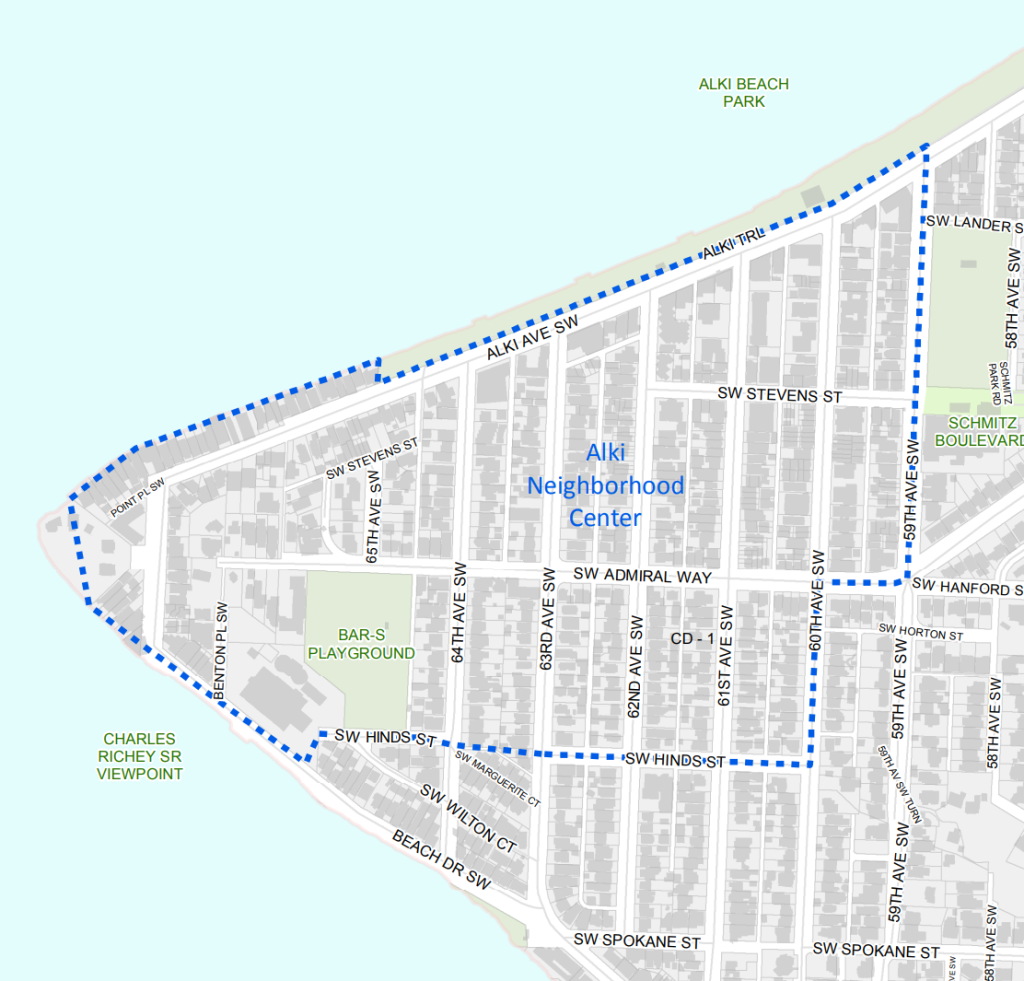

Perhaps nowhere are the tensions between land use and school policy more on display than in Alki, where Seattle Public Schools has almost completed construction on a brand new elementary school building that will boost the capacity at the site to more than 500 students, compared to 370 at the previous school building. While Seattle voters have consistently approved school construction levies, paving the way for school rebuilds like this one, it’s the Seattle Public Schools operating budget that is feeling the financial crunch.

When SPS put forward two potential lists of schools being considered for closure last year, nearby Lafayette Elementary was included on one of those lists. Located in the Admiral neighborhood, Lafayette is one of the most walkable schools in the neighborhood, and sits directly in the middle of an area where the city is focusing more housing growth in the One Seattle plan. But if that school were to close, many of the families would instead need to commute to Alki or to an even more remote school, Pathfinder near Delridge Way.

More students living closer to Alki could help sustain the entire neighborhood’s school ecosystem, but only if the City of Seattle allows that to happen. As it stands, Alki could end up being not a neighborhood school, but a destination for long commutes from elsewhere in West Seattle.

Nonetheless, the idea of allowing additional housing in Alki has met significant opposition within the neighborhood, including from the Alki Community Council, becoming a particular flashpoint among the eight proposed neighborhood center additions.

District 1 Councilmember Rob Saka, who has focused attention on Alki during his term by prioritizing the area for traffic calming infrastructure ahead of more dangerous corridors elsewhere in the district, came out strongly opposed to the idea of an Alki Neighborhood Center late last week. An amendment Saka put forward to pull the center from consideration in 2026 ultimately failed, meaning it will remain on the Comprehensive Plan docket.

In speaking in favor of his amendment, Saka railed against the proposed Neighborhood Center, citing “very very limited” access to transit — a fact that likely won’t change much without additional housing density. The current Route 50, which connects Alki with Alaska Junction, SoDo, and Southeast Seattle, runs every 20 minutes throughout most of the day, but is a very circuitous route that isn’t competitive with driving. He also brought up “environmental risk” as a reason why Alki is not a good fit for a neighborhood center.

“Alki sits directly on Puget Sound’s shoreline, making it one of the city’s most vulnerable areas to sea level rise, storm surge, and erosion” Saka said. “Encouraging new growth in this high-risk area conflicts directly conflicts with the Comprehensive Plan’s climate resilience principles.”

Apart from the technical case against an Alki Neighborhood Center, Saka painted advocates for additional housing in the area as not being from the neighborhood, suggesting that only neighborhood residents should get to weigh in on whether growth in the area makes sense.

“We’ve heard the term NIMBY, not in my backyard YIMBY, yes in my backyard. I think as part of these specific conversations there’s a new term, maybe: YITBY, yes in their backyard,” Saka said. “It’s easy for some people — some people not from a community — to say something is best for them, and if that thing is implemented, they’re completely unaccountable, and they don’t have to manage the day-to-day as a direct result of that.”

Seattle’s school district, on the other hand, does have to manage the day-to-day reality of a severe school funding crisis. As the city council takes a closer look at the additional neighborhood centers in 2026, including at Alki, they’ll likely want to afford significant weight to the school board directors tasked with finding a way out of that crisis.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.