Last week, transit advocates had the rare opportunity to hear an in-depth hour-long conversation from Sound Transit’s top officials. Transportation Choices Coalition hosted a “Transit Talk” with Sound Transit CEO Dow Constantine and Deputy CEO Terri Mestas. The conversation centered around getting the Sound Transit 3 (ST3) measure on course after the agency recently revealed a major budget shortfall exceeding $30 billion.

Spurred by an audience question, Constantine also discussed the agency’s latest thinking on Seattle’s second downtown transit tunnel. In short, new technology and system upgrades could allow the agency to operate significantly more trains in the existing tunnel. If successfully implemented, that technology could make running three light rail lines in the existing tunnel conceivable.

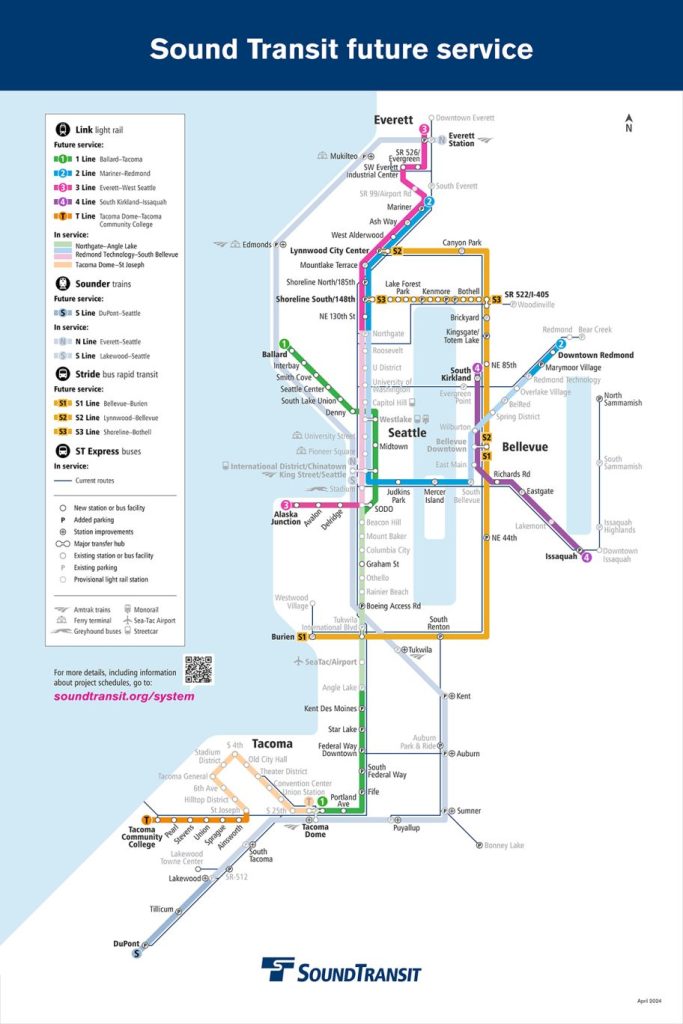

The ST3 plans envision those three primary lines as running from Redmond to South Everett, Tacoma to Ballard, and Everett to West Seattle, all passing though a Downtown Seattle tunnel on their way. A fourth line would also operate from Issaquah to South Kirkland, as the final light rail project planned to be built.

As it stands, agency plans would make the second downtown tunnel a key part of the 10-station Ballard Link project, providing the highest ridership stations on the line. Cost estimates for Ballard Link have spiked, jumping from $11.9 billion to upwards of $22 billion.

A viable plan to operate three lines in the existing tunnel could make jettisoning Seattle’s downtown tunnel enticing as a cost-cutting measure — especially to suburban boardmembers from outside Seattle. A few of them have essentially already proposed as much. Sound Transit Boardmember and System Expansion Committee Chair Claudia Balducci put forward the proposal to study the idea of operating the three lines in the existing tunnel.

Balducci is also running for King County Executive, which would give her the most powerful seat on the Sound Transit Board of Directors. (The Urbanist elections committee endorsed Balducci in her bid; I serve on the committee with 13 other members.)

Technology could jam more trains through Seattle’s existing tunnel

Asked if Sound Transit had already looked at using one downtown tunnel for all three of the agency main light rail lines, Constantine said they had vetted the idea early on, but that technology has changed since then, potentially making the idea feasible and more practical.

“So this was studied pretty extensively a decade ago as we prepared to move forward with Sound Transit 3, and the conclusion of time was that we needed a second tunnel for capacity, because there just wasn’t enough room for all the trains in the single tunnel we currently have, as well as redundancy, so you don’t have a single point of failure,” Constantine said. “If something happens in the tunnel, you have to bus around it. Conditions have changed. We are on a much tighter budget now, and building the tunnel involves, potentially, choices about building other projects.”

Balducci has not yet endorsed abandoning the second downtown tunnel, but she has argued that more information is needed to make the decision.

“Boardmember Balducci has asked us to revisit this question,” Constantine said. “Now, in addition to that condition having changed, that there are probably tough tradeoffs, there’s also the fact that technology has changed. There’s now something called communication-based train control, which, when installed, allows the trains to automatically run much closer together. So, more trains on the infrastructure you build.”

Communication-based train control partially automates trains, increasing safety while allowing tighter headways. But it is not the only infrastructure upgrade that would be needed to boost train frequencies in the existing tunnel.

“Our tunnel still has constraints,” Constantine said. “There are some areas where there are not enough ventilation, emergency ventilation zones, so you have to space [trains] a little farther apart than the communication-based train control would allow. But the point is that there are ways to put more trains through the tunnel than there were back when we studied this the first time.”

Other tradeoffs are at play as well. Not building the second tunnel would leave the agency with one bottleneck for the entire system, and less redundancy in the case of maintenance work or unexpected outages or blockages in the tunnel.

“The single point of failure is still a real challenge,” Constantine said. “It would be nice to have a new tunnel so we could completely shut down the old tunnel and refurbish it end to end. There are questions about whether the platforms are big enough in certain places where a lot of transfers are taking place.”

The questions of undersized platforms at some existing Downtown Seattle stations could well be exacerbated if they are serving three lines instead of just two. If Sound Transit doesn’t build the second tunnel, it will need to undertake these major projects to upgrade the existing tunnel while still operating the system, which would likely mean massive disruptions to service.

Constantine alluded to the fact that Sound Transit’s study could prove the opposite point: the analysis of trade-offs may end up showing the second tunnel is needed and possibly indispensable, building a case for sequencing it first, if Ballard Link ends up being segmented into multiple projects.

The price tag for installing new train control technology and shoehorning bigger platforms and potentially more escalators, stairs, elevators, and beefed up ventilation systems is not yet known, but it could also be well into the billions. That would lessen the savings from shelving the second tunnel.

All this is before grappling with the question of how to tie Ballard Link into the system without a new tunnel for that purpose. Ballard Link will need to have a connection to Sound Transit’s central train base in SoDo in order to operate, and the second tunnel was to be that connection. Without it, Ballard Link would need a new underground interchange with the existing tunnel just north of Westlake Station — an extremely challenging and costly engineering feat — especially since the agency would want to minimize disruptions to existing service in the tunnel.

The only other alternative is for the agency to overhaul its plan and add a new train base in Interbay or Ballard for the sole purpose of serving the orphaned Ballard Link line that terminates next to Westlake Station. As a new project element, the new train base would need be designed from scratch, meaning delays to Ballard Link being a shovel ready project. Sound Transit would need to acquire significantly more land in Seattle for a duplicative maintenance base.

While the challenges to Ballard Link are significant without a new tunnel, not building the second tunnel also comes with some advantages, such as greatly reducing construction impacts in Chinatown-International District (CID) — a thorny issue that has already pushed Sound Transit to overhaul plans in 2023, and redo an environmental study, delaying the project. Constantine backed the move to abandon the station planned in the heart of the CID and in Midtown (near the Seattle Central Library), instead adding stations to the north and south of the CID. The new “Midtown” station is close to the existing Pioneer Square station.

Constantine pledged to present the board with the fullest accounting of tradeoffs the agency could.

“On the other hand, it would solve some of the challenges with International District impacts. We make transfers from Eastside to southbound trains easier,” Constantine said. “There are some advantages leaving aside cost to interlining all the trains. So we’re studying it again at the boardmembers’ request. It is a board policy choice, and I’m going to do my best to present the board with all the facts, including the tradeoffs implied, and allow them to chew on that and make a decision.”

Mestas elaborated that the agency is modeling a vast variety of scenarios to analyze how the future system will grapple with operational challenges. That analysis should allow the agency to have a good sense of the relative brittleness or resilience that the network would feature under each buildout scenario — and how soon the system might be running up against capacity constraints.

“The way that we are doing this assessment is through a rail simulation,” Mestas said. “So, this is just using technology tools so that we can model the system in different ways. With the tunnel, without a tunnel, we can also look at a variety of different solutions. Things are going down, something’s not working — we will get thousands of iterations of scenarios to understand what the impacts are. So, we’re working on that right now. We have a lot of great national experts supporting us in this work, and we hope to have the results of that to help inform also making that decision.”

Enterprise Initiative

Earlier this year, Constantine unveiled the Enterprise Initiative, which he framed as a system-wide effort to rebalance the agency’s long-range financial plan with tools other than project delays and cuts.

“Historically, what we’ve done in these moments is simply turn to capital and start either canceling or delaying projects, extensions, garages, what have you,” Constantine said. “What we wanted to do is take a more holistic view and take a more thoughtful approach to balancing our long range financial plan.”

He pointed to the work that Mestas is leading to better manage projects and cost pressures by implementing best practices in infrastructure management and making decisions more nimbly in hopes of lessening the bite that inflation takes out of budgets. Sound Transit also intends to look at increasing efficiency in operations, exploring new financing tools as part of the Enterprise Initiative, and evaluating control cost drivers in other aspects of the agency’s work.

Mestas’ cost control work is not focused primarily on jettisoning projects. In fact, the agency is investigating whether investing a bit more in capital upgrades upfront could pay dividends in the long run with more efficient operations and greater ridership.

“In your home, it might be cheaper to keep your own furnace, for example, but if you convert it to a new heat pump, it’s an upfront investment, but over time, you’re going to save money, and you’re going to be cool in the summer as well,” Constantine said. “So better service, less money.”

Part of the argument for the second tunnel is ensuring that the agency can provide frequent service as its system grows and ridership spikes. Since all three lines of the future light rail network, stretching from Tacoma to Everett, run through Downtown Seattle, the tunnel pinch point will set the upper limit for frequency on all three lines. The agency could find that a second Seattle tunnel is the heat pump in this analogy.

“Now, I don’t think this is about building the tunnel or not building the tunnel,” Constantine said. “I think this is about where in the sequence of projects do you build the tunnel. Do you build it first? Or do you build some of the extensions and then come back when you have capacity to build a second tunnel to get your resiliency and your redundancy? We’re going to find out. We’re going to find out whether it’s possible, what investments have to be made in the existing tunnel, what the tradeoffs would be, and the board’s going to have to wrestle with some really tough choices.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.