As state lawmakers returned to Olympia this week for the start of their short, 60-day legislative session, many of the items on the wish list of potential statewide housing reforms have already been checked off over the past few years.

In 2023, the state’s landmark middle housing bill and one of the most permissive accessory dwelling unit (ADU) bills in the nation raised the floor on minimum residential density. The legislature followed up with a full legalization of single room occupancy buildings in apartment zones the following year, and in 2025 knocked out three other major reforms: parking reform, transit-oriented development (TOD), and rent stabilization.

With so much already accomplished and limited time to advance bills in 2026, the pace of action on the issue of housing this year is expected to slow. The number of housing bills that were prefiled ahead of the session’s first day Monday was much lower than it had been during those banner years on housing, and the scope of those bills have turned from sweeping to wonky and targeted.

While the legislature had been tackling the elephants in the room — exclusionary zoning, outdated development standards, and costly government mandates — now it’s turning its attention to the thousand paper cuts that make housing in Washington more expensive.

“There’s still more to do, but I think that in terms of these really, really big regulatory regimes, we’ve sort of put those in place, and it’s less the cities are pushing us, and more like we need the state to write the model code,” Representative Julia Reed (D-36th, Seattle), the author of 2025’s landmark TOD bill, told The Urbanist. “We need the rule-making process to play out. We need some of the actual enforcement process to take place.”

Legislators are expecting more space to focus on the nitty gritty.

“So that’s why you don’t see a rent stabilization [bill] in this session, or, a TOD or an [HB] 1110 because, we’ve been really successful in getting this done, which is really great,” Reed added. “It also means there’s some things on the edges that you know didn’t get done because we were really focused on some of these bigger bills.”

Senator Jessica Bateman (D-22nd, Olympia), chair of the housing committee in that chamber, cited another reason legislators aren’t tackling as many major initiatives in 2026: the state of the budget. With a significant budget gap to fill over the next two months, proposals that come with a cost to state government will face a high bar to clear.

“Legislation that costs money this year, there’s going to be a fine-tooth comb process for reviewing those; they have to have a lot of merit,” Bateman said. “Because of the budget situation that we’re dealing with, anything that we add to the bucket of costs is going to be something that we have to figure out how we address it, by revenue or cuts. And we made a tremendous amount of cuts last year, and that’s not something any of us are looking forward to.”

Strip malls into housing?

This zoning bill likely to make the biggest splash this year is SB 6026, which would require mid-sized cities and urban counties in Washington to allow residential uses in any areas that are zoned for commercial businesses. Sponsored by Senator Emily Alvarado (D-34th, West Seattle) at the request of Governor Bob Ferguson, the bill would encourage the redevelopment of underutilized commercial properties, and ban cities from requiring ground floor retail spaces within those development projects.

“Washington needs to make it easier, and more affordable, to create more housing units of all kinds — faster,” a release from Ferguson’s office touting the bill stated. “This is one way to increase access to affordable housing. For example, an abandoned strip mall or shuttered big-box store could be turned into housing without having to go through the process of changing its zoning to residential.”

Another housing bill from 2021, HB 1220, is already forcing cities to reckon with how much land could potentially be rezoned to accommodate denser housing, with many of those cities looking at commercial zones located in places that have long been neglected. Woodinville, for example, is set to rezone a swath of commercial property along a state highway to accommodate multifamily development, a move that brought criticism from King County’s affordable housing committee from the perspective of equity and environmental justice.

As one of the bill’s co-sponsors, Bateman acknowledged that many areas zoned commercial today are close to major arterial roads, which means new residents added to those areas would be forced to contend with disproportionate amount of pollution, noise, and traffic safety issues. But she sees the idea as providing the type of flexibility around zoning that will be necessary to truly start building at the scale Washington needs to.

“We’ve seen the status quo before we passed all of these historic housing bills — you saw cities that really concentrated a lot of their multifamily [housing] on the edge of town, next to arterials or next to commercial industrial and that’s not really the vision that I see for this bill,” Bateman said. “I see this as freeing up and providing flexibility where currently none exists. You’re still going to have to take into account those types of scenarios and situations, but not simply just having a categorical rule that you cannot have housing in some of these areas, I don’t think makes sense, and so we’re looking for flexibility in that. Obviously, we still want places that are livable and walkable.”

SB 6026 is set to get its first hearing this Friday, at 10:30am in the Senate housing committee.

Elevators and stairs

One of last year’s closely watched housing bills is almost certain to return in 2026: the first legislation attempting to revamp residential elevator standards anywhere in the U.S. Put forward by Senator Jesse Salomon (D-32nd, Shoreline), SB 5156 would have directed the state’s department of Labor and Industries to legalize smaller elevators in all buildings six stories or shorter that include 24 units or less. With existing requirements for elevators to be large enough for a full 24-inch by 84-inch stretcher, many smaller multifamily buildings are being built with fewer elevators than they might otherwise, or oftentimes no elevator at all.

The bill met heavy resistance from both firefighter groups and the unions representing elevator mechanics, which have pushed to maintain existing standards for elevators — unique to the U.S. and Canada — that maintain their tight control over the market. Rather than directly implement a change, SB 5156 is likely to be modified to request changes to elevator standards from the state building codes council.

“This year, I think the track we’re going to take is to just kick it to the building codes council to adopt smaller elevator standards — that will be less controversial,” Salomon told The Urbanist. “The original bill was tasked with coming up with and adopting European elevator standards. That’s a lift. That was more of a message to regulators on the national level just hopefully start looking at that.”

The Sightline Institute has a new video laying out the case for elevator reform.

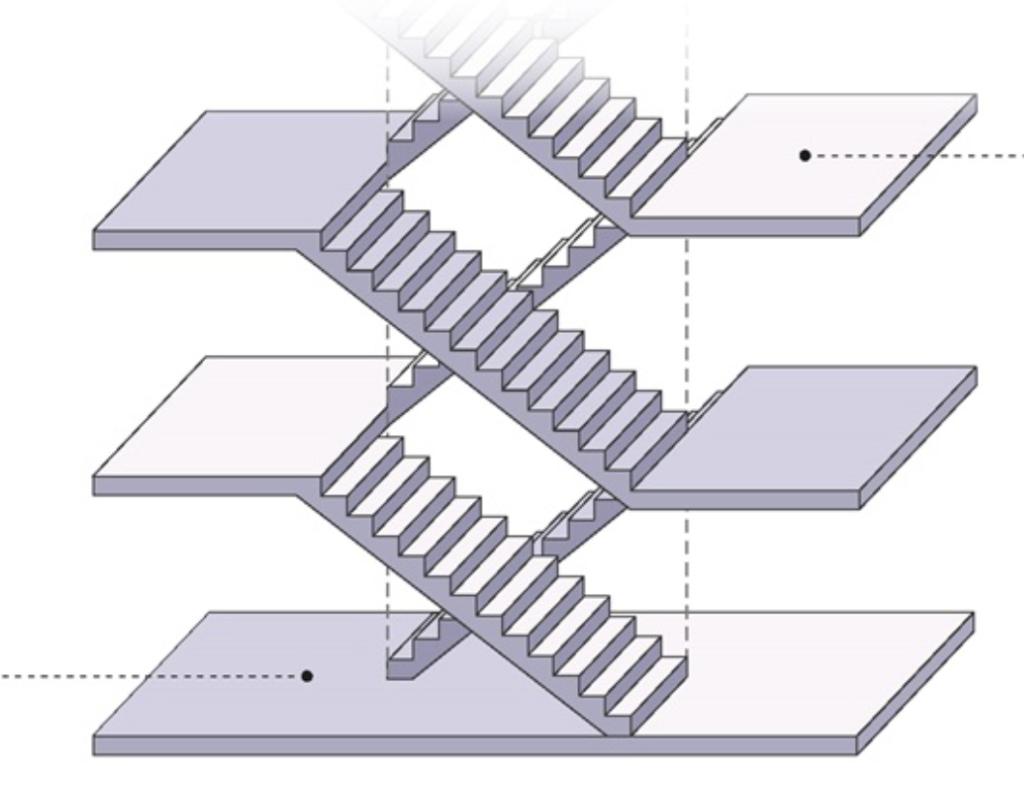

Also in the vertical circulation space, HB 2228 would legalize scissor stairs as a type of egress allowed in multifamily construction. This would allow builders to fit more housing in the same-sized building by wasting less space on stairs and hallways as they meet the requirement to provide two separate exits in the case of fire. Scissor stairs are quite common in places like Vancouver, B.C., but have not yet been legalized throughout the U.S. This bill is sponsored by Rep. Janice Zahn (D-41st, Bellevue), who joined the legislature last year after serving on the Bellevue City Council for nearly a decade.

“Scissor stairs allow for less space dedicated to stairs, hallways, and elevators in a building and more space for living space. This allows for the entire building to be skinnier or more compact than the buildings we typically build in Seattle, which saves on the amount of land needed to construct the building and the overall construction cost because one is constructing a smaller building,” housing advocate Markus Johnson wrote in an op-ed in The Urbanist last year.

HB 2228 also gets a first hearing this Friday morning, in the House’s local government committee.

Another bill set to return from last year is HB 1443, which would allow property owners to build mobile dwelling units (MDUs), a movable home with its own utility connections, usually added next to an existing home on a residential lot. Sponsored by Rep. Mia Gregerson (D-33rd, Burien), the bill received approval in two House committees but never reached the floor.

“It’s one of the most economical forms of housing for people,” Bateman said. “We’ve worked on accessory dwelling units, middle housing, all these different housing types and varieties, with the goal of providing options for people. And this is a really great option.”

The idea of allowing MDUs brought significant opposition from the Association of Washington Cities in 2025, over concerns that the dwelling units fall into a gray area of housing types and that local governments wouldn’t have very many tools to be able to regulate them.

“Although the bill was amended in several ways, it still allows an RV or pop-up trailer — now two — to park in every residential driveway and allow someone to live in it for an undefined period,” the local government advocacy group wrote of the bill last February. “Except for providing specifics on utility connections and inspections, the bill prohibits inspection of the ‘residence.’ Who safeguards the living conditions? Except for tiny houses with wheels, the rest of ‘mobile dwellings’ are not designed as permanent housing. These vehicles are designed for temporary camping and are prone to mold over time. Are these folks considered tenants? The bill does not provide protection under the Landlord and Tenant Act.”

Housing funding and legal liability

Zoning and development regulations are just one piece of the puzzle of getting more housing projects to pencil, with issues around financing now looming after Washington’s recent housing moves. One bill put forward this year to tackle the need to unlock dollars for affordable housing is SB 6028, also put forward by Alvarado. It would set up a revolving loan fund, with builders eligible to borrow dollars if they include housing affordable to households making 80% of a county’s area median income or below, with the projects that include the most affordable housing deemed to be more competitive for the loan dollars.

Additionally, the legislature is set to take another crack at condominium reform this session. Last year, lawmakers took a small step toward addressing one of the biggest barriers hindering condo development in Washington: strict liability standards that often mean lengthy lawsuits. This in turn has pushed many developers out of the condo market. Lawmakers adopted incremental reforms that exempt condo builders from “implied warranties of quality” that apply to larger condo buildings if their building is two stories or fewer, with a max of 12 units.

HB 2304, sponsored by Rep. Jamila Taylor (D-30th, Federal Way) expands that to four stories, making it much more feasible to construct a small multiplex development and sell the units as condos.

While few bills will likely garner the banner headlines seen in 2023 and 2025, this year’s proposals all push in the same direction: making it more feasible for builders to be able to make headway toward the more than one million new homes that Washington is projected to need over the next two decades, particularly if it wants to make a dent in its affordability crisis.

“We have done most of the big policies for sure, and we continue to hear, it’s not enough,” Rep. Davina Duerr (D-1st, Bothell), chair of the House’s local government committee, told The Urbanist. “I’m still hearing complaints about the permitting processes and how long the timelines are. We have to remember, though, just because we passed something doesn’t mean it’s been implemented yet. So a lot of these things we passed, but they’re not in play yet, or making a difference. A lot of the permitting reforms that we did were only implemented this summer, so it’s too early to know, but it’s also a very difficult sort of funding environment too. So we continue to chip away.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.