“It’s dead.”

Rico Quirindongo, the head of Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development, did not mince words when bringing up the Center City Connector, the long-deferred project to finally connect the city’s two disconnected streetcar lines. In early January, Quirindongo was briefing the Seattle Planning Commission about the City’s growth plan for the downtown area, a proposal that conspicuously leaves out the beleaguered project.

“There’s no money. It’s not in the transportation plan, the federal dollars that [Mayor Jenny] Durkan put on hold, those are not coming back to us, and the price to do it is twice as much as it was five years ago. It’s dead,” Quirindongo told the commission.

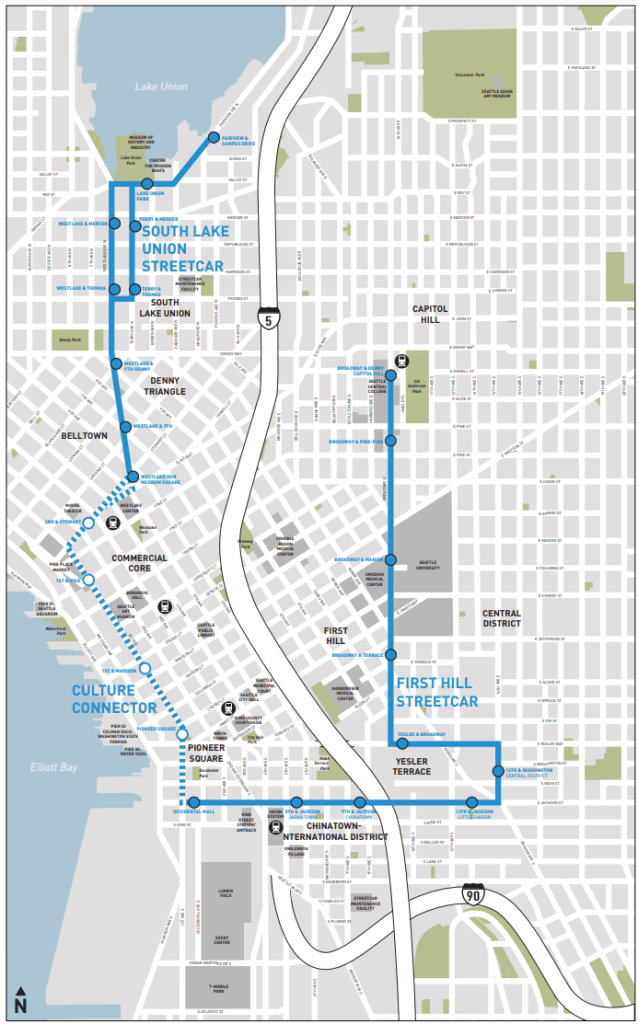

Though an off-the-cuff moment of candor, but Quirindongo is likely not wrong. The current cost estimate to build the 1.27-mile connection along First Avenue, uniting the First Hill and South Lake Union streetcars together into a unified system, has skyrocketed to at least $410 million. Even if the City were able to re-secure the $75 million recommended to the project by federal officials in 2016, no City dollars are earmarked for the project.

The Seattle City Council voting to remove the project from the city’s Capitol Improvement Program in 2024 appeared a final nail in the coffin. An effort to restart the project and once again win federal grants would have to contend with a Trump administration that is much less friendly to transit projects — especially in Blue states.

A price tag edging into the half-billion range is daunting for a local streetcar or rapid bus project, though it’s basically a rounding error for a Sound Transit light rail project. The latest estimates put West Seattle Link as a $7 billion project and Ballard Link at more than $20 billion.

Incoming Mayor Katie Wilson told the Seattle Times last year that advancing the First Avenue streetcar was unlikely to be prioritized if she were to take office, while at the same time criticizing prior administrations for stringing the project along. Various Seattle Mayors had embraced the project to varying degrees since it was first studied in 2012 under Mike McGinn. Most recently, Bruce Harrell embraced the idea in theory, rebranding it the “Cultural Connector,” but didn’t make any substantive moves to secure funding.

“I doubt that the Center City Connector will emerge as a funding priority in my first term. Either way, we owe voters a clear explanation, and a commitment to never again let projects like this stagnate for so long,” Wilson told columnist Jon Talton last fall.

Bridging the network through downtown was expected to significantly increase ridership on the whole system, and the lack of that connection clouds the future of the two existing lines, which were built for different purposes without a long-range vision for the decades ahead.

This Friday, the First Hill line turns 10 years old, a piece of transit infrastructure that has matured into a workhorse of the city’s transportation network. As detailed recently by the Capitol Hill Seattle Blog, the 10-station line between Pioneer Square and Capitol Hill has nearly surpassed its pre-pandemic ridership numbers, becoming more than twice as efficient as the overall King County Metro bus network at moving people per service hour.

The First Hill line’s success stands in stark contrast with the South Lake Union line, which opened in 2007 and is not expected to return to its very modest 2019 ridership levels until sometime in the 2030s, if ever. At just 1.3 miles long, South Lake Union line is too short to be useful to many transit riders, while the First Hill line is nearly twice as long.

While more than 1.2 million riders jumped on a First Hill Streetcar in 2024, the South Lake Union line saw less than 20% of that figure, and has been hovering around 200,000 annual riders since 2022 — lower usage numbers than many Metro bus routes. While the First Hill Streetcar has surpassed 4,000 daily riders, the South Lake Union is consistently living well below 1,000 daily rides.

Despite return-to-work policies prompting employees in South Lake Union to go back into the office, many of those workers are choosing other modes, including bus routes that didn’t exist when the streetcar first opened, like the C Line and the Route 40. Soon the J Line will provide another option a few blocks away on Fairview Avenue.

Across downtown, streetcars would not be scurrying up and down Jackson Street if not for Sound Transit, and its 2005 decision to skip a light rail station in First Hill on the way to North Seattle. Designing a tunnel that could serve First Hill and then jog back around to Broadway and John Street proved to be a technical feat that the agency couldn’t confidently accomplish, and so the streetcar became the neighborhood’s consolation prize. In addition to paying for the majority of the $135 million needed to build the line, Sound Transit agreed to pay $5 million per year for operations — but only through 2023.

The limited duration of that funding agreement means the City of Seattle is now primarily responsible for maintaining an asset that was intended to connect riders with light rail indefinitely. While King County Metro is responsible for funding core bus service in Seattle, the agency has never taken the same responsibility for funding streetcar operations, even as it serves as the operator through a contract agreement.

As costs to maintain the two lines have increased, past City leaders had to get creative about funding sources that could plug the gap between dedicated streetcar revenue (including fares) and what it actually costs to keep the system running. Recently, the Harrell administration turned to the 2020 Seattle Transit Measure to plug that gap, a voter-approved funding stream directing a 0.15% sales tax toward bus service and related investments.

Six years ago, the City subsidy going into the Seattle Streetcar network was $5.4 million, a number has gone up to $13.4 million this year, dollars that could be used elsewhere in the city’s transit system. The 2026 budget adopted last fall diverted funding from transit capital upgrades — spot improvements intended to improve passenger amenities or speed up buses — into the streetcar budget to account for expenses growing more rapidly than expected.

The Wilson administration will face a choice around the streetcar system within just a few months, as they assemble a proposal to renew the 2020 transit funding measure. Wilson herself is already signaling that service levels and transit reliability will be her primary focus, and an early executive order this month targeting improvements for the Route 8 on Denny Way cites the benefits of a “robust, reliable transit network.” Without an entirely new funding source, choosing to continue to subsidizing the streetcar system with transit measure funds will coming with an opportunity cost, limiting Wilson’s ability to invest in transit more broadly.

Another hurdle on the horizon: the South Lake Union streetcar will likely have to shut down for as long as eight years during construction on Sound Transit’s Ballard Link Extension to allow for construction of the station planned at Westlake Avenue and Denny Way. That looming infrastructure project, which Wilson will put her stamp on as she joins the Sound Transit board this month, will likely color the entire discussion around what to do about the South Lake Union line.

The First Hill Streetcar celebrates its birthday this week as a successful piece of the transit network, a line that has fulfilled its mission to connect riders in one of the city’s densest neighborhoods with light rail. But the storm clouds on the horizon for the Seattle Streetcar are getting harder to ignore.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.