Sound Transit is steaming toward some of the biggest decision points that the agency has seen in at least a decade, with pivotal choices ahead around how to balance a $34 billion shortfall set to come in front of the board in a matter of weeks.

On the line are Sound Transit’s ambitious system expansion plans, with many elements of the 2016 Sound Transit 3 (ST3) ballot measure at risk of delays or, even worse, lines stopping short of where voters were promised high capacity transit. Over the past year, Sound Transit has been undertaking what it is calling the Enterprise Initiative, an agency-wide attempt to think outside the box when it comes to saving costs, all in an attempt to avoid a repeat of a similar financial crisis in 2021 that resulted in enshrining numerous project delays.

All of this work is expected to come to a head at a March 18 board retreat, where various scenarios to close the budget gap will be put on the table. This month Sound Transit staff has been putting different options in front of the board, assembling what are being framed as the “building blocks” for decision making that will occur later this year. Unlike with the 2021 realignment, these puzzle pieces impact every corner of Sound Transit work, from the policies its lobbyists have pushed in Olympia to the way that it plans operations.

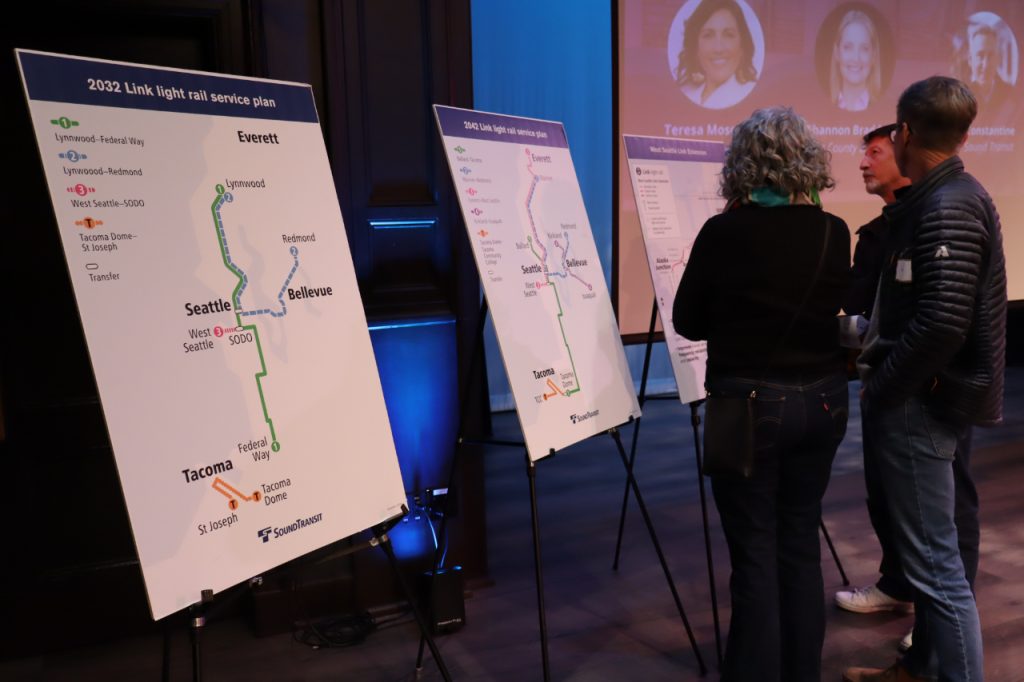

System expansion building blocks

When it comes to expansion projects, which are center stage for most riders, the board has been getting briefings on potential cost savings uncovered since late last year through the work spearheaded by Deputy CEO for Megaproject Delivery Terri Mestas and carried out by Sound Transit’s capital team. Some of those measures have been relatively small changes that unlock a significant amount of dollars, while others are much more impactful, like the wholesale removal of stations.

The board has looked at adjustments to the West Seattle, Everett, and Tacoma lines in isolation, and it’s still awaiting a full breakdown on the largest ST3 project, Ballard Link. Until last week, the agency hadn’t provided its board with a wide-angle view at all of this cost savings work collectively.

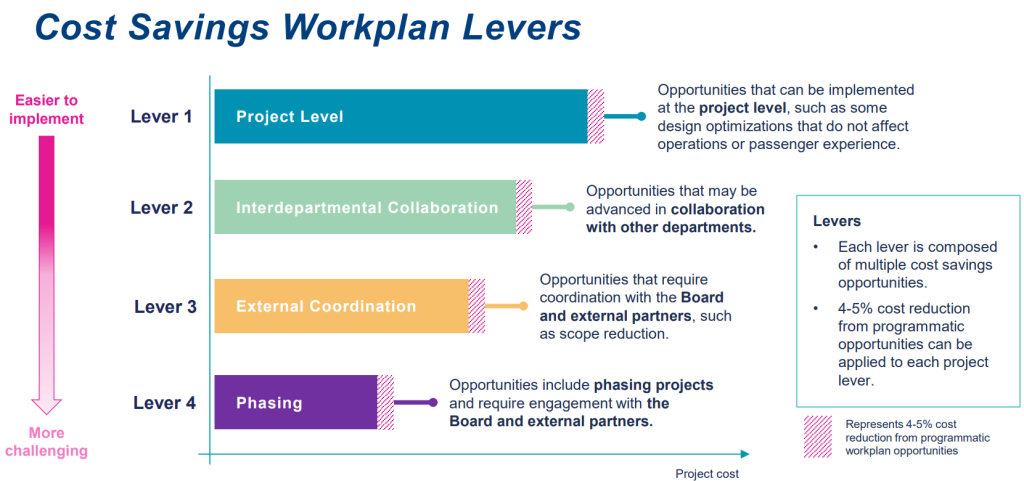

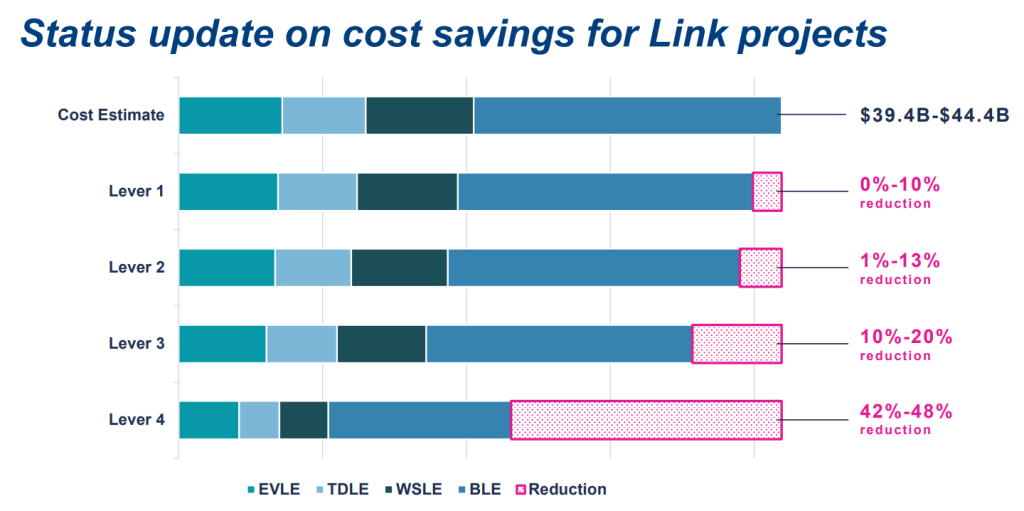

Sound Transit staff have been putting cost savings measures into four different tiers, or “levers.” The levers ramp up in complexity and potential impact on riders or agency operations: lever 1 is relatively straightforward changes that are clear no-brainers. Lever 2 changes are slightly more complex, and lever 3 changes are the type that would need buy-in from local governments and other stakeholders due to their significant impact on the project’s scope and footprint.

Lever 4 is essentially the nuclear option, and would involve phasing entire lines and coming back later to complete them, an option that no board member wants to turn to when it comes to the line in their district. Rather than getting all the way to Tacoma Dome, the 1 Line would be extended only to Fife. Other lines would only make it as far as Delridge Way, Smith Cove, or SW Everett Industrial Center.

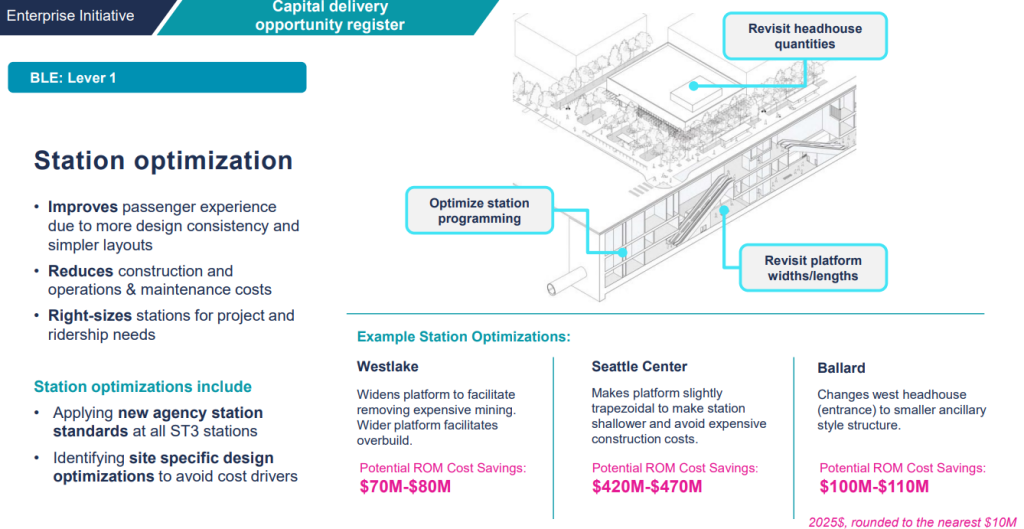

The Lever 1 changes are not all small potatoes. Last week, the board’s system expansion committee got a look at some of the tweaks on deck for Ballard Link. That project raised alarm bells when its estimated cost jumped from $11.9 billion to upwards of $23 billion. An adjustment to the station platform design at Seattle Center station could save as much as $470 million just by making the platform “slightly trapezoidal.” That adjustment was able to change the entire orientation of how Sound Transit would excavate the station box to accommodate the station.

Amazingly, this amount of funding is equal to the dollars that could be saved by eliminating the entire Avalon Station from the West Seattle Link Extension.

“The number is quite large. It seems too large to believe sometimes,” Brad Owen, the Executive Director of the delivery team handling the Ballard and West Seattle extensions, said in response to a question about that one change from board member Steffanie Fain. “Changing the shape allowed us to bring the station up. It costs so much to take dirt out of a giant hole downtown.”

It was a striking moment that illustrated just how much funding can be unlocked via strategic thinking.

But the bottom line, as shown to the board last Thursday, is that pulling levers 1 through 3 right now only unlocks around 10% to 20% of cost savings, which is below what the agency has said is needed to stay on schedule. Without creative problem-solving, the agency will be forced to pull lever 4, and the battle over which projects see phasing could take over the work happening as part of the Enterprise Initiative.

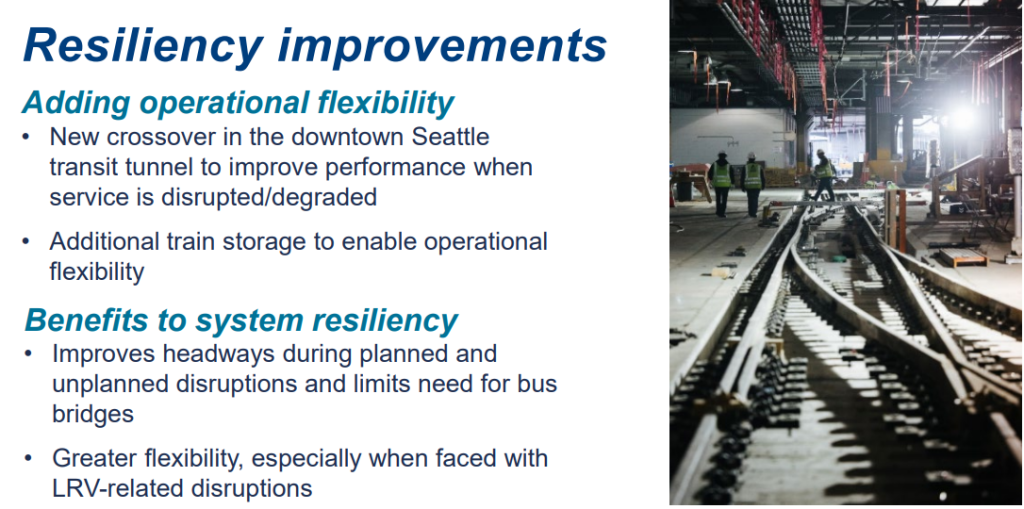

In December, the board did look at an option that could potentially save much more money by phasing a different portion of the ST3 network, the second tunnel planned under Downtown Seattle. But that idea, put forward by longtime board member Claudia Balducci, was put to the side. The consensus among board members was that construction risk was high and that running three lines through the existing tunnel would be too disruptive to operations and too damaging to the system’s long-term resiliency.

Nonetheless, when the full range of potential paths forward becomes clear, the idea may end up getting put back on the table.

Operations

Sound Transit is also scouring its operations division for savings. As the system grows, costs to maintain stations and operate service becomes a bigger and bigger part of its balance sheet. For the most part, the cost savings identified from Sound Transit operations come from changes to the expansion projects: shorter lines mean fewer dollars spent on operators, security staff, and fare ambassadors. But that doesn’t mean that Sound Transit isn’t scouring its operations division for potential cost savings that could help it offset some of the budget crunch.

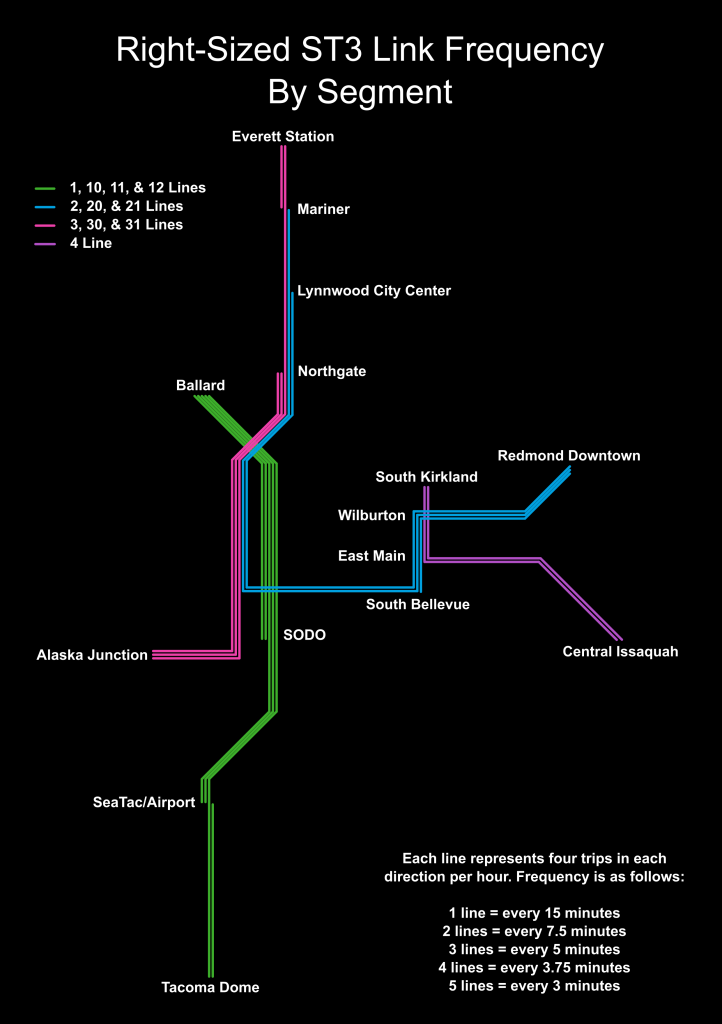

So far, Sound Transit is assuming train frequencies will remain largely uniform across a system set to grow to 116 miles. In 2023, Urbanist contributor Stephen Fesler laid out a plan to right-size service patterns, by running extra service in the busy core of the network and economizing elsewhere. While presenting political challenges, Sound Transit may eventually be forced to think along these lines to stretch its operations dollars farther.

The agency is looking ahead to work that will need to happen to maintain a resilient light rail system. With the long-running pattern of costs increasing with time, tackling work early can save Sound Transit money over the long term. However, slotting in big upkeep projects may not always be possible due to the extreme budget pressures that system expansion projects are creating.

Sound Transit knows that the Downtown Seattle Transit Tunnel is an Achilles heel of the entire network right now, with a lack of crossover tracks and other outdated infrastructure creating real liabilities for future expansion projects that depend on that tunnel. Those upgrades are going to cost money — and they could end up being more expensive and more painful if the agency waits to do that work, kicking the can down the road.

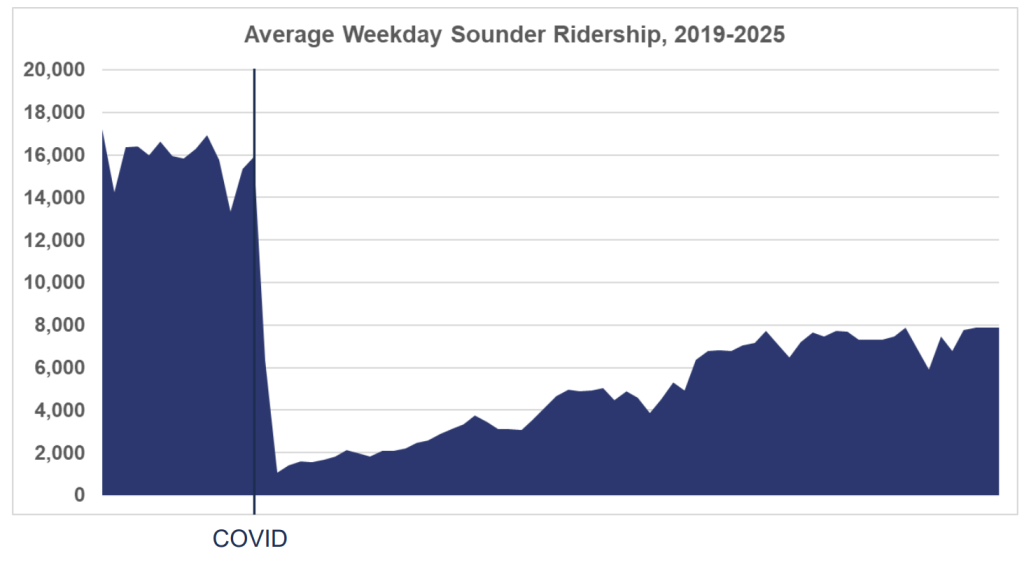

Additionally, Sound Transit is zeroing in on potential adjustments to how it operates Sounder, its two commuter rail lines to Everett and to Lakewood.

With Sounder ridership settling into a clear post-pandemic holding pattern — at less than half of what it was in 2019 — the need to accommodate large numbers of peak riders on trains and platforms is much less pressing. Instead, broad agreement exists among both board members and the public that Sounder should be shifting to an all-day service model that matches rider demand.

That means some of the projects that are on deck for the coming decades may not be needed: chiefly a $454 million project to lengthen Sounder stations to accommodate longer trains, expected to be completed by 2036. With trips distributed throughout the day, running more trains might be a higher priority than spending that money on expanding peak capacity for demand which may not materialize.

The agency also might take a look at a $333 million planned Sounder maintenance base, expected to open by 2034, and consider other options that include continued contracting with Amtrak, expanding its own maintenance base in SoDo. And then, there’s an extension planned to DuPont by 2045, expected to cost $882 million. While not as front-and-center as the ST3 light rail projects, all of these expenses are expected to be part of the conversation.

Policy & planning

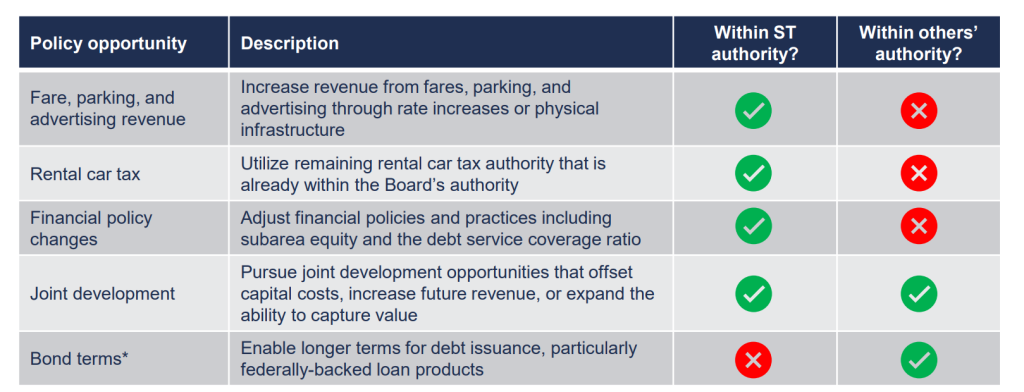

Sound Transit is also looking at policy levers that can be pulled independently of direct decisions around service expansion or operations.

The agency’s work to consider fare gates and other fare enforcement mechanisms fall into this category, along with potential expansion of paid parking programs at Sound Transit’s extensive park-and-ride facilities.

Meanwhile in Olympia, Sound Transit is supporting a number of bills that would move policy levers in various departments. There’s a proposal to allow the agency to tap into federal authorization to issue 75-year bonds, which CEO Dow Constantine said could allow for more flexibility when considering how to pay for its biggest future assets, like the second downtown tunnel.

There are also a pair of bills that would significantly streamline how Sound Transit works with local governments on its permits, allowing multiple phases of permitting to move forward concurrently rather than having to happen one after the other. Both of those proposals are moving forward, but may not make it to the finish line before the end of the legislative session in mid-March.

With so many moving pieces to consider, the big question in the weeks ahead will be how much of an active role the board will take. Will board members roll up their sleeves and look at how the different “building blocks” truly work together, or will they mostly roll with the easiest options, pitting the more powerful corners of the Sound Transit district against areas that are less well-represented? That all remains to be seen.

While we don’t know what the outcome will be, the table has been set.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.