In my last article on linkage fees I made the case that the typical supply and demand dynamics we are familiar with from buying gasoline or coffee do not work with land development. Land is different from nearly all other types of goods because when demand goes up we can’t make more of it and when demand goes down we can’t ship it somewhere else or break it into its components and turn it into something else. Land supply is perfectly inelastic–a change in land price doesn’t change the amount of land–and a linkage fee, therefore, will not change the supply of land. But a significant question remains: won’t landowners simply hold back land from the market until prices rise again, effectively (if not technically) lowering supply?

If this is true it could be a major problem for linkage fees. If landowners refuse to sell until prices return to their pre-linkage fee levels, developers are no longer able to recover the cost of the linkage fee by paying lower land prices. Development costs go up and we are back in the familiar supply-and-demand negotiation where renters lose, developers lose, or both lose.

Naturally, we can’t directly test how linkage fees will affect how much property is brought onto the market because it is merely an outline of proposed legislation at this point (although two developers in an anonymous survey conducted by Vulcan suspected anticipation of linkage fees becoming law would push land prices down). We can, however, indirectly test the effect of linkage fees by examining market data more generally.

After reviewing the available evidence, I can say with about as much confidence as one can honestly muster from the messy business of real estate research that land supplied to the market is not diminished during periods of falling land prices and, conversely, land supplied to the market does not increase during periods of rising land prices. Property supplied to the market does change month-to-month but it does not correlate with trends in the market value of properties. That is, taking it one step further, development fees that lower land values would not restrict land from being made available to the market.

Why Landowners Sell

Before getting into the evidence, it’s worth just thinking about what motivates landowners to sell or hold their land. A rational landowner — the Econ 101 financially self-interested market actor — holds or sells land based on anticipated future income of that land compared to all the available alternatives. If anticipated income is greater than all the financial alternatives of selling the land and putting that money to some other use, then the rational landowner holds on to the land. If it is less, she sells it and invests in Blue Chip stocks or tulip futures. What doesn’t influence the rational landowner is past losses. The rational landowner is always trying to maximize future returns, not recover past losses.

The typical landowner is not a financially self-interested market actor, of course. Most of Seattle’s landowners live in the homes they own. For these relatively risk-averse landowners, holding may be the favored choice because owning the land and profiting off its use provides more stability (if less income) than selling the land and investing it somewhere more lucrative (and having to find a new place to live). What makes landowners offer their property to the market? It probably has a lot to do with life cycle changes: a new job, marriage, divorce, retirement, or the death of an owner and the transfer of land into a trust to be sold and the proceeds divvied up as inheritance (this is often how farms become residential subdivisions).

I mention these two types of landowners for two reasons. The first is that despite having different motivations about when they may choose to sell property, neither motivation is guided by comparing past prices to present prices. The second reason is that a good set of historic commercial sales data is expensive and, additionally, commercial land is so heterogeneous due to size, location, zoning, etc. to make comparison to other variables often unsuitable.

Market Evidence

In order to test the criticism that landowners sell less when prices decline I first examined how stock market trading volumes change in relation to price. Undoubtedly, the stock market is an imperfect analogy for the real estate market but it is easier data to get and offers a much larger set of data points to test the claim made by some opponents of linkage fees.

Yahoo! Finance

Here we can step back and look at the relationship between price and volume over three booms and two busts in the last 20 years of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. There is no correlation or, rather, there is no positive correlation between price (line) and volume (bars) in the stock market. If anything, volumes are highest around the bottoms of the two busts and have declined gradually since the market recovery began in 2009.

The correlation between price and volume has been studied in decades of financial research with varying conclusions. A short overview of this research can be found in Chapter 3 of this MIT course document (pdf file). A 2011 study (pdf file) attributes historically high trading volume in recent years to the declining cost of making stock trades. Generally, though, the research has found that absolute price change is correlated with trading volume but not necessarily positive price change.

If linkage fees restrict real estate market activity, and the reason it does this is based on bedrock economic principles so as to be generalizable to the stock market, we should not see what we see in the chart above. Trading volume and stock price are marching to two different drummers.

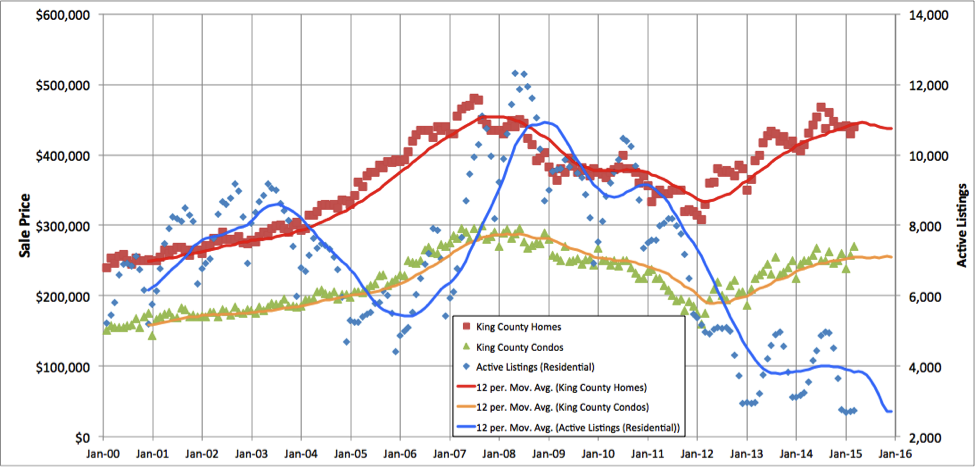

But that’s stock market behavior and we’re just interested in real estate market behavior. In order to get closer to the question at hand–do price changes in real estate affect real estate available to purchase?–I examined monthly reports from the local multiple-listing service (NWMLS) and compared active listings (properties for sale) to sale price averages for homes and condos. This data (Excel file) is neatly compiled and provided by Seattle Bubble, a local real estate blog. I have placed 12-month moving average lines on each set of data to control for seasonality. The data runs from January 2000 to March 2015, the most recent update.

The chart reveals that although there are periods where price and active listings appear to move in tandem there are also periods where they appear to move in opposite directions, the last three years being especially dramatic as the real estate market recovered while listings declined to their lowest levels in at least 15 years. Again, if some linkage fee critics are right, we should expect more active listings as sale prices go up and less active listings as prices decline. The evidence does not support that claim.

Linkage Fees Are Fair, Effective, and Feasible

As an initial response to the criticism that landowners would withhold properties from the market should linkage fee legislation pass, I attempt to challenge the claim using presently available public data, the best we can hope for with untested legislation. The evidence shows that declining property values do not decrease supply available to the market and, conversely, increasing values do not bring more properties onto the market.

Without a doubt, increasing supply by making it easier to build multi-family housing in Seattle is an important and worthy policy goal. We need to do it. We need to make design review more effective. But we don’t need to legislate two sinks in aPodments. And we need more multi-family options all over the city. In addition to these efforts we need to work towards capturing windfall land profits which are primarily responsible for the increased cost of housing in Seattle and many other growing cities.

The Economist article that quickly sped around the internet a few weeks ago concludes that a land tax is effective and fair but politically and logistically difficult. The Linkage Fee, though, is easy to administer and a politically achievable policy that works much like a land tax. It will produce lots of new affordable housing supply by stuffing the housing trust fund with the proceeds of what is effectively a capital gains tax on land sales.

Photo credit: i don’t live here anymore (detail), Christine Hou

Michael Goldman

Michael works as a real estate valuation analyst. He graduated from the University of Washington with a Masters in Urban Planning and a specialization in real estate. Before Serial broke the long-form true crime scene wide open, he had a podcast about pet adoption.