In a previous article, I responded to Dan Bertolet’s rebuttal of my essay outlining why urbanists must support linkage fees. My primary argument, that land is inelastic, means that land supply doesn’t increase when prices go up or decrease when prices lower.

Land was sometimes defined in classical and neoclassical economics as the “original and indestructible powers of the soil.”[1] Georgists hold that this implies a perfectly inelastic supply curve (i.e., zero elasticity), suggesting that a land value tax that recovers the rent of land for public purposes would not affect the opportunity cost of using land, but would instead only decrease the value of owning it. This view is supported by evidence that although land can come on and off the market, market inventories of land show if anything an inverse relationship to price (i.e., negative elasticity).

Inelastic land supply is incompatible with the theory that landowners will hold land off the market at lower prices. While the debate about the elasticity of land is important, it’s actually unnecessary. Even in a world with elastic land supply, the linkage fee wouldn’t reduce housing supply.

Connecting The Supply Of Land To Housing Supply

Overall, the rebuttal of the linkage fee did four things. It asserted that land is elastic. It then told a story about why landowners would hold their land off the market. It went on to explain why evidence showing the success of inclusionary zoning is insufficient. Finally it suggested there are better alternatives to linkage fees.

To engage further, I’ll entertain the assertion that land is elastic. With that assumption, I will examine if landowners will wait to sell until they get the price they want. I will look at an example property going through multiple sales. Then I will examine if holding some land off the market could affect housing supply. Finally, I’ll run through the stories being told about the market and implore urbanists to refocus on housing limits, rather than regulatory costs.

The Role Of Development Capacity

The rebuttal article begins by drawing a line between land values and development capacity. To be clear, development capacity doesn’t cause development. Everyone should repeat this to Lesser Seattleites claiming, “Seattle has plenty of development capacity.” This is also the most logical response to Bertolet’s initial points regarding development capacity.

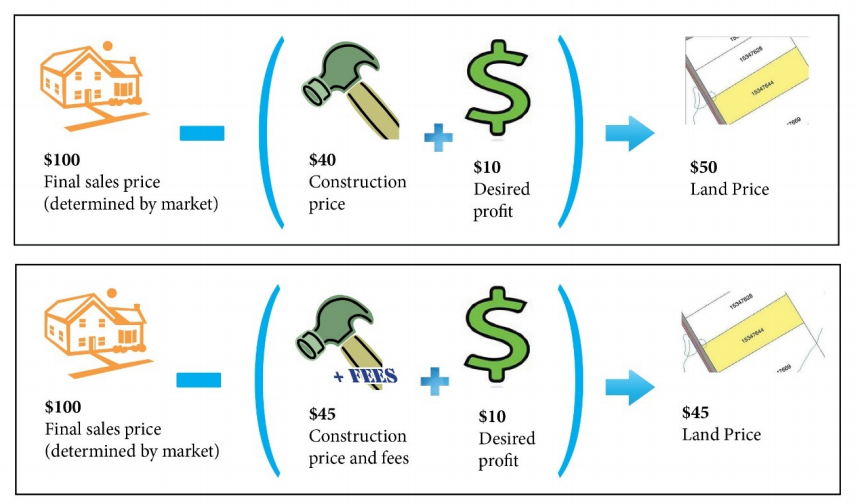

Land value is determined by calculating the potential revenue a property could earn and subtracting the cost to reach that potential. Improvement value on the other hand is the assessed value of current improvements.

Bertolet’s rebuttal begins by describing the common model for determining redevelopable land:

the ratio of the value of the improvements on the land, to the value of the land itself. The larger the ratio, the less likely a property will redevelop.

He shows that less land is measured as ‘redevelopable’ when property values drop without improvement value changing. This analysis is useful for understanding development capacity but he then says:

we can see that because a linkage fee reduces land value but not improvement value, it skews that ratio towards predicting no redevelopment.

To put a finer point on it: Pickford’s position contradicts the standard methodology used by the City of Seattle, King County and countless other municipalities to estimate “buildable land,” that is, land that can be redeveloped. This alone should be enough to cast serious doubt.

Suggesting linkage fees won’t affect housing supply can’t contradict the standard methodology because the methodology doesn’t make predictions about housing supply. Development capacity models are primarily used to guide development to particular areas and predict if development is possible. Comparing land value to improvement value is a proxy for understanding if parcels are at their maximum use. But a drop in land value due to a fee doesn’t necessarily reduce the potential usage of a property.

It even turns out that there are different methods for determining redevelopable land. As an example, the Snohomish County Buildable Lands Report prepared by EconoNorthwest says:

Note that redevelopable land, as it is typically defined, deals primarily with parcels with developed structures that are judged as likely to be demolished and new buildings constructed in their place. The standard approach to identifying redevelopable land is to compare improvement value to land value. Many analyses assume that tax lots where improvement value falls below land value (a 1:1 improvement to land value ratio) are redevelopable. Not all, or even a majority of parcels that meet this criterion for redevelopment potential will be actually redeveloped during the planning period. The issue of how much of the potentially redevelopable land will be assumed to redevelop over the planning period needs to be considered.

An alternative approach to estimating redevelopment potential is to analyze the relationship of parcels to other surrounding parcels. For example, some jurisdictions define redevelopment potential as parcels that have improvement values significantly lower than surrounding parcels in similar designations. This approach, however, requires a property-by-property analysis using advanced GIS tools.

Another approach to estimating redevelopment potential is to analyze land value as a function of parcel size. In general, one would expect larger parcels with lower improvement values to have higher redevelopment potential. The distribution allows analysis of the relationship between improvement value and parcel size, and shows clear breakpoints in that distribution.”

The second method doesn’t even consider land values. Instead it just uses relative improvement value. But just like land value, improvement value isn’t a cause of development. Overall, the important point is that the models aren’t predicting development and neither improvement or land value cause development.

At What Price Are Profit-Maximizing Landowners Willing To Sell

It’s often stated that the city can’t simply reduce the value of someone’s land by fifty percent and expect them to sell. But what does this mean? The claim seems to rest on the assertion there is a tipping point for landowners to sell. A price too low and the landowner won’t sell. When the price is high enough, development will happen. Bertolet points to the development capacity model as a way to understand this but I don’t think that’s the best way. To represent this tipping point, I think the profit-maximizing landowner who received a bid from a developer would ask, “over the long run, is it more profitable to keep my property at the existing use or to sell it right now.” There are a lot of reasons selling might be better:

- Rents should be higher in a newer building because it’s new and often has more units;

- Operational costs may be increasing and income decreasing due to building age;

- Landowners may want to cash out and enjoy retirement; and

- A dollar now is worth more than a dollar in the future due to interest, investments and risk.

On the other side, there are costs to development. Obvious costs include things like; loans, labor, materials, demolition and regulation. But the known costs are shared by nearly all developers and are largely handled during bidding for land. The big cost is the risk of lower than expected demand, like a recession. This is why many developers went bankrupt during the last recession. They sunk costs into building and then their income evaporated. Everyone should keep this in mind when skewering developers as evil or taking insane profits.

Looking At An Example

To understand whether or not a landowner will sell, I’ll discuss a real example. Outsider guesses at the impact of linkage fees on land values vary widely from 5% to 40%. In previous comments, Bertolet indicated 25% and he’s pretty close. If we look at the history of the parcel containing the Sunset Electric, we can see a linkage fee would’ve reduced land value by 20%. The 2012 buyer of this property would’ve had to consider, at worst, a $22 per square foot linkage fee because of their plans to redevelop. The building that now occupies that lot would’ve garnered about $1.35 million for affordable housing, or 20% of the $6.7 million price tag they paid for the property.

So if the bid for land in 2012 was 20% lower, would this have been enough to sell the property? The previous owners, 11th and Pine Associates, bought the property in 2006 for $3.275 million in 2012 dollars. They left the property empty the entire time they owned it, indicating nearly any price would’ve been greater than the income from the existing use.

Why did I choose this property, which didn’t already have income? It actually tells a decent story about how development happens. Developers typically target under-utilized properties. The property also appears to be an example of land speculation. It’s possible the 2006 buyers intended to develop the property and the recession got in the way but even considering that, the property was unused for at least a decade. During that time the property value increased more than 300%. It’s hard to believe a 20% lower land value, garnering over a million dollars for affordable housing, would’ve prevented or slowed a sale according to the logic of comparing existing uses to potential income.

Instead this evidence indicates landowners trying to cash out at the market peak, an entirely rational way to treat an asset like land. Unlike the developers that built the new Sunset Electric building, the money speculators received wasn’t from value they created. Furthermore, this development didn’t become possible because the land value hit the right level. The development became possible because Capitol Hill became a more desirable neighborhood, in a wealthy, growing city; the same reason the land value increased. The linkage fee would simply capture some of this value so that those with less money can continue to afford housing.

Anecdotal evidence can be misleading and no one should put too much weight on this example. But it’s more useful than theoretical stories. Linkage fee opponents will likely show an example of a project that wouldn’t ‘pencil out’ if linkage fees existed. This strategy is similar to the businesses suggesting a higher minimum wage would require laying off workers. It doesn’t acknowledge the fundamental economic shifts that will apply to everyone. Like the business that can raise their prices, because everyone else in the city also raises their prices, developers can lower their land bids because all other developers have to as well. Since we can’t trust anecdotes though, the reason I feel relatively confident is because this has been done in other cities. It turns out the reliable research show basically no affect on housing supply. This is more important than stories or anecdotal evidence.

But What If Fewer Landowners Are Willing To Sell

Under the worst scenario, some landowners are unwilling to sell for some period of time. This doesn’t even consider that upzones could increase the value of land. It also ignores all the arguments about inelastic land supply. Remarkably, even if this happens the fees should still work.

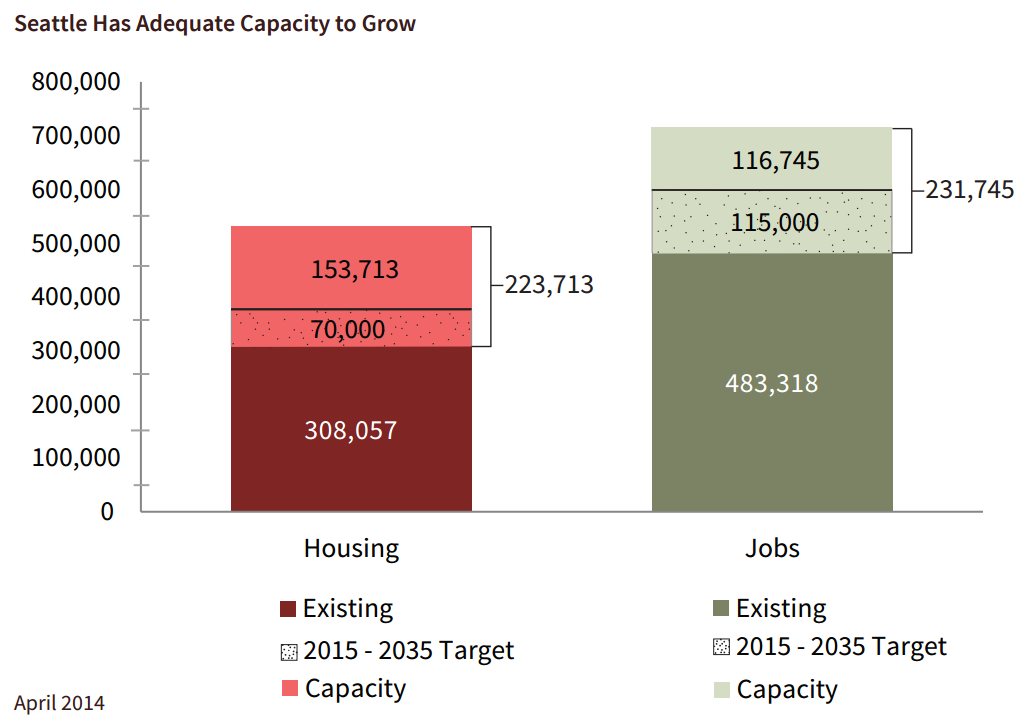

In order for housing supply to be affected through land, there has to be too few redevelopable parcels. If the development capacity model is related to the amount of redevelopable parcels, or the number of property owners willing to sell (something Bertolet is at least implying) this conclusion is unrealistic. The development capacity model estimates capacity for 223,713 housing units. While this isn’t a perfect model, Seattle isn’t lacking capacity. I’m not familiar with a clear explanation of how development capacity affects housing supply but opponents to linkage fees haven’t presented this either.

With that said, the assertion that fewer willing landowners mean less housing supply relies on some reduction in redevelopable capacity. In fact the reduction would have to be enough to prevent the amount of development that would happen. Last year developers only built about 8,000 units, or 3.5% of the redevelopable capacity. Would there have been less development if capacity had been 150,000, 100,000 or 10,000 units? Is it reasonable to think that a 20% decrease in land values would result in a 10, 20, 50 or 96.5% reduction in capacity? If capacity actually decreased drastically, would the Department of Planning and Development do nothing to increase this capacity? These are important questions for linkage fee opponents but they remain unanswered. Instead opponents focused on hypothetical stories about how market actors behave.

Stories We Tell About ‘The Market’

First, I found the retiree narrative confusing. The story goes that a potential retiree will hold their land off the market due to lower bids:

Slap on a million dollar linkage fee, and maybe they’ll wait it out through the next development cycle—perhaps 7 years or more—until market rents rise enough to offset that million dollar hit to their nest egg caused by the linkage fee.

Where did the million dollar fee come from? This would likely require a sale price in the millions of dollars. Apparently, adding millions to their retirement nest egg isn’t enough to retire, nevermind the fact that waiting 7 years might actually result in less money due to a recession. Or the fact that a retiree will likely want money sooner so they can spend it before they die.

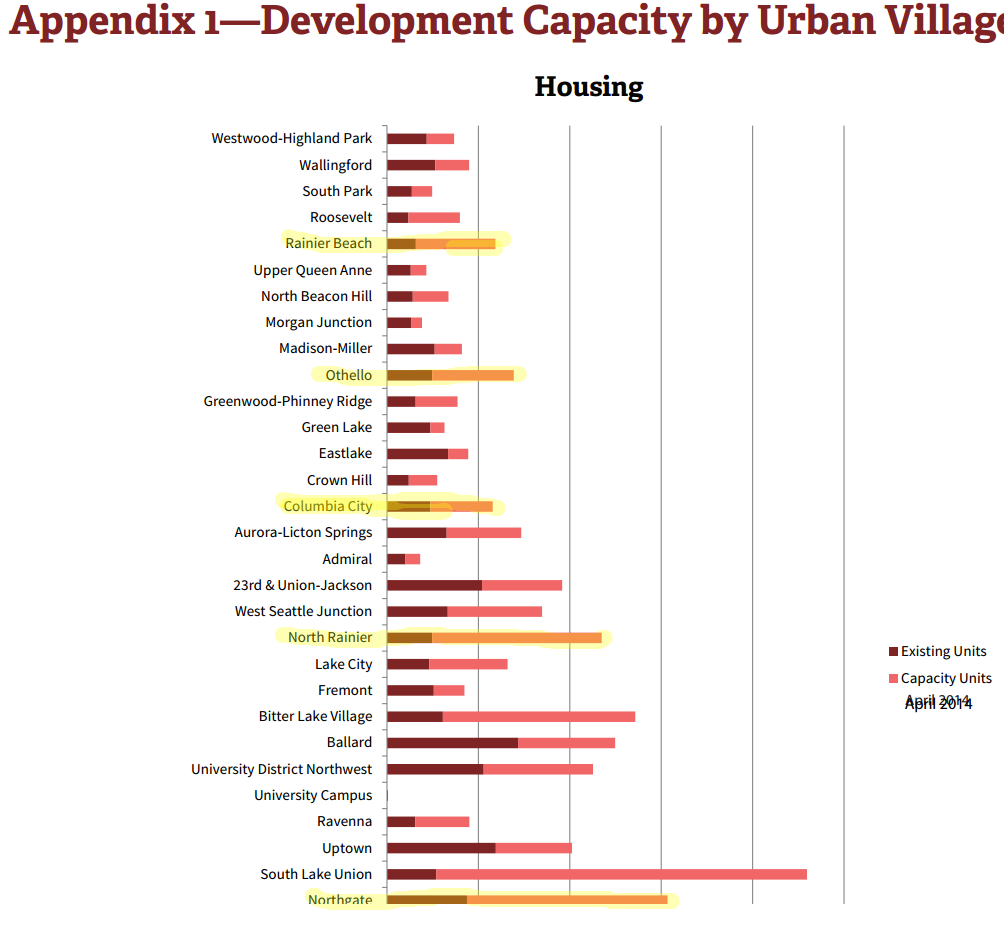

Another confusing argument is that the fee makes development less likely in areas needing development, such as Northgate and Rainier Valley. It’s arguable these places ‘need development,’ just ask those worried about displacement. Overlooking this concern, my interpretation of this argument is that some people think these areas aren’t economically feasible:

A linkage fee’s level of impact on these hold/sell decisions will depend on the value of the existing uses relative to the land. And where it will have the greatest tendency to hinder sales for redevelopment is in areas with lower land values where feasibility is currently marginal, such as the Rainier Valley, Northgate, and the International District—in other words, the very locations where the City most needs new housing to meet its goals for sustainable development.

But the model cited by Bertolet – not the model used by developers – shows these areas have lots of development capacity. This again gets at the tenuous relationship between land value, improvement value and actual development.

I think a more compelling explanation for why these areas aren’t seeing development is that they are relatively less profitable. Contrary to the claim he makes, his logic suggests the fee would likely increase the appeal of Rainier Valley and Northgate. The proposed fee is tiered from $5 to $22 dollars and these areas have the lowest fees. If a high fee discourages development a relatively lower fee should relatively increase development.

Moving on, readers find another archetype, the incompetent government bureaucrat. He says:

Given that every development project is unique, and given how the market varies over both geography and time, it’s delusional to believe that the City could set a linkage fee rate in some kind of “sweet spot” that wouldn’t end up sabotaging land transactions for redevelopment.

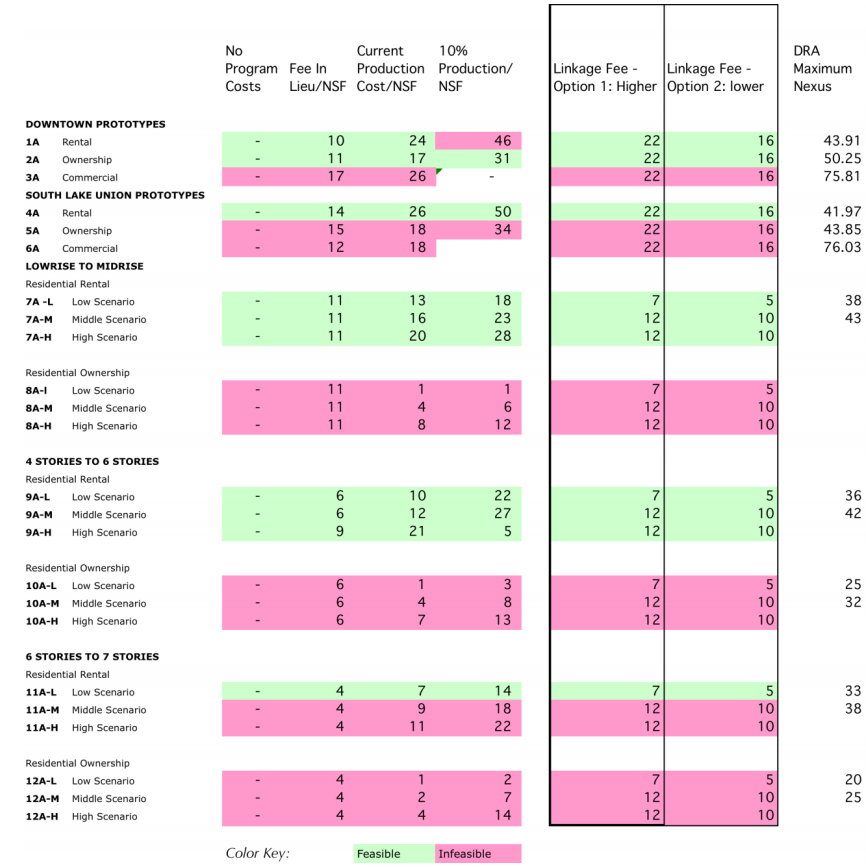

Immediately following this he goes on to say the evidence showing no affect on supply is weak because some municipalities enacted density bonuses with their inclusionary zoning programs.

If an IZ program is “revenue neutral” it means that it would not cause any reduction of land value, and therefore no impacts on housing production would be expected! In contrast, Seattle’s proposed linkage fee offers zero in the way of cost-offsets. Thus the results of all of the California IZ studies should be presumed to have minimal relevance to linkage fees.

In other words, inclusionary zoning was successfully implemented in nearly every municipality studied. Even though bureaucrats are incompetent they somehow managed to find both an appropriate fee level and an appropriate density bonus. Perhaps most importantly, if density bonuses work, there’s no reason the upzones we’ve already done wouldn’t work with some level of fee over the long run.

Again, the most charitable way to interpret these objections requires accepting there could be a level at which the fee would work. If that’s the case, it makes sense to trust the analysis provided by the city that actually worked through the math indicating development could handle the proposed fee. This analysis estimates that the proposed linkage fee would be equivalent to a 3-5% set aside of affordable units. This is both modest and cautious compared to the 10-20% set aside seen in most areas studied with successful programs.

Let’s Increase Development (Not Just Capacity)

Getting to the end result of more development is complicated. Increasing development capacity would be a good start. This fits perfectly with my call for urbanists to focus on housing limits, rather than regulatory costs.

No urbanist wants to reduce development capacity and most, including myself, want to increase it. But most urbanists know less development capacity doesn’t equal less development or vice versa. Pursuing efforts to improve the quality of the city, such as ensuring mixed income neighborhoods and equitable access to urban benefits, shouldn’t be avoided because of affects on development capacity. We shouldn’t get rid of Seattle City Light’s efforts to make buildings more energy efficient just because it increases improvement value.

What this tells me is that we need to focus on housing limits. Good urbanists have spent a lot of time and energy on reducing housing limits. I made this argument by providing evidence that regulatory costs probably don’t affect development. There is compelling evidence this approach is accurate. But even if it’s not, it doesn’t mean urbanists should focus on land values, improvement values or regulatory costs. There is not a straight line between regulatory costs and housing supply. There is a much clearer line between housing limits and supply.

To drive the point home, many regulatory costs improve the quality of life in Seattle. This is why affordable housing and social justice advocates support linkage fees, the fees will help achieve integrated neighborhoods in a way other affordable housing programs can’t. But the battle against regulation goes beyond linkage fees. In fact, opposing regulations aimed at making the city nicer draws a line between urbanists and many other advocacy groups since quality of life is so closely related to development. Affordable housing advocates read Bertolet’s article and perceive a battle with urbanists. Is a battle with the neighborhood greenways and transit advocates next? Or should we just move on to fighting education activists? If regulatory costs don’t affect supply or even have a marginal impact, this is extremely counter-productive.

It’s also counter productive if efforts to remove housing limits will overwhelm other factors. Political outcomes are unpredictable and can have unintended consequences. As an example, I believe Bertolet’s argument inadvertently provides evidence linkage fees will cause upzones. The city is required by law to plan for growth by expanding development capacity when it drops below 20 years of growth. If we see declining capacity due to lower land values, the city will likely pursue upzones to meet GMA requirements. By definition lower land values would create the impetus for further upzones.

There are great urbanists that disagree with my view; reasonable people can disagree. I don’t expect them to change their minds; people rarely do. But my take is that the best we can do when trying to understand economic outcomes is to look at empirical research. I’d be happy to continue looking at research regarding land elasticity or the effects of linkage fees but I don’t think Bertolet’s rebuttal presented any new empirical evidence. Instead it focused on a narrative story. Furthermore, after dismissing the evidence provided he claimed the burden of proof is on The Urbanist. I disagree and believe the burden of proof should be on those that have not presented supporting evidence. Most importantly though, I believe a successful urbanist political effort will require focusing on things that most clearly harm housing supply, housing limits. It will also require building coalitions with natural allies that want regulations making the city more livable. If no one changes their mind about linkage fees, urbanists could still refocus on housing limits. In the end, if urbanism is going to be a viable political force, I believe urbanists must distinguish between the efforts to eliminate regulations and the fight to eliminate housing limits.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.