Walking and biking rates have been steadily increasing throughout the Puget Sound Region over the past decade, a trend that has been particularly significant in urban areas. A 2014 regional commute study by the Puget Sound Regional Council found that walking and biking represented 12.3% of all commute trips. In 1999, the combined rate for walking and biking commute trips was a mere 7%, meaning that the non-motorized modes experienced a 75% increase over the 15-year period.

Two researchers, Xi Zhu and Cynthia Chen, from the University of Washington released a new study last year to determine what factors affect the rates of walking and biking amongst different income groups. Their research reaffirmed findings of similar studies that show an increased propensity to walk or bike for people living in denser neighborhoods where access to local jobs, services, and other amenities is abundant. In the Seattle area, this propensity to walk or bike is held in common amongst urban dwellers regardless of income status. But it’s from there that the data quickly diverges between low- and high-income groups.

Zhu and Chen based their research on a 2013 survey sent to households throughout King County. Astonishingly, the survey asked respondents over 100 different questions ranging from the quality of their built environment to how they make transportation choices. Using a locational sampling methodology, researchers were able to isolate their research to the highest and lowest density residential neighborhoods near the State Route 520 corridor.

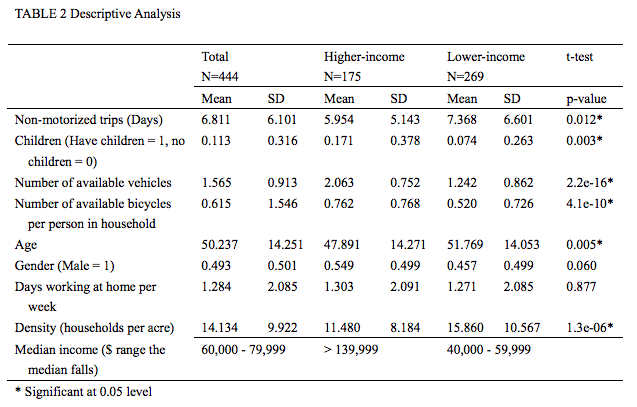

Amongst those surveyed, researchers determined that the median annual household income fell between $60,000 and $80,000 for respondents. Broken into low-income and high-income groups, the researchers found that the median annual household income for low-wage earners was between $40,000 and $60,000 while for high-wage earners it was more than $140,000. Looking at household demographics, the data suggests significant differences between income groups:

- High-income households tend to be slightly younger.

- Low-income households have considerably lower access to a private motorized vehicle.

- High-income households are more likely to have children.

- Low-income households are more likely to live in a higher density neighborhood.

- High-income households have a much higher ratio of bicycles available to household members.

- Low-income households make modestly more non-motorized trips.

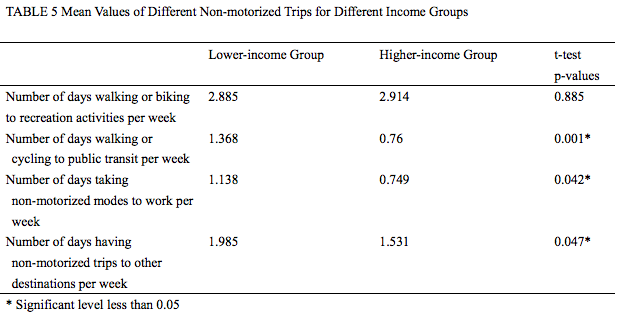

Researchers were able to establish specific reasons for walking and biking between income groups:

Lower-income groups use significantly more non-motorized modes to work, to public transit stations, and to destinations other than work (mandatory activities) and recreational (discretionary) activities, i.e., they likely walk or cycle significantly more than the higher-income group when going to do maintenance activities (e.g., shopping). The only destinations that the lower-income group uses less non-motorized modes are recreational trips, though the difference is not significant.

The table below shows these attributes definitively.

Researchers also found four other important differences amongst low- and high-income groups:

- Private ownership of a motorized vehicle affects the rates of walking and biking for low-income households. The effect is so great that for each additional motorized vehicle owned, a low-income household walks or bikes 2.5 fewer days in a given week. Meanwhile, access to private motorized vehicles for high-income households does not affect their likelihood to walk or bike.

- Neighborhood density also affects the rates of walking and biking for low-income households. Higher neighborhood densities were associated with increased walking and biking rates for low-income households. Yet surprisingly, high-income households did not respond to higher neighborhood density with increased walking or biking rates.

- Perceived accessibility to destinations increases walking and biking for low-income households. The more pedestrian-friendly or bicycle-friendly that an area is, the more likely low-income households were to walk or bike. These factors, however, did not spur high-income households to walk or bike more.

- Perceived neighborhood attractiveness increases walking and biking for high-income households. Neighborhood attractiveness is centered on the aesthetics of buildings, streetscapes, and amenities. The more attractive that a neighborhood is, the more likely that high-income households will walk or bike. Low-income households did not respond in the same way.

Both income groups responded positively to ownership of bikes. Households that owned more bikes saw an increase in the number of days that individuals in the household walked or biked. In fact, for every additional bike in a household, the number of days that someone walked or biked in a week increased by 1.1 and 1.2 days, respectively.

Fundamentally, the research boils down to two key themes for the respective income groups:

- Low-income households respond to community density and accessibility to destinations. The easier it is to walk or bike places and the more people and things that an area has, the more likely low-income households are to walk and bike. Their economic situation, however, appears to dictate how they make trips, meaning that they aren’t exactly a choice. Therefore, their trips are more likely to be associated with mandatory and maintenance trips.

- High-income households respond to community attractiveness. The more attractive an area is, the more likely they are to walk or bike. Therefore, their trips are more likely to be associated with recreational trips.

Researchers suggest that policymakers should see this study as both encouraging and challenging. It’s clear that the built environment dictates how individuals will respond with walking and biking habits. However, low- and high-income households respond very differently. In the case of low-income households, walking and biking rates increase with community density and accessibility. Yet, as their economic situation improves, their propensity to walk and bike is eroded due to higher motorized vehicle ownership. Meanwhile, high-income households are only sensitive to the aesthetic qualities of communities, meaning that increasing walking and biking rates amongst that group would require investing in neighborhood beautification.

So then, if these are the factors at play, what do we do to increase walking and biking amongst all income groups?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.