Perhaps due to upcoming budget deliberations, the Seattle City Council took up a crowded legislative agenda on Monday with 35 pieces of legislation (many which were appointments). The Council approved important policy changes on plastic bags and the Living Building Program, and also weighed in on preservation of a new landmark, a new business improvement area, and easement and property acquisition for a North Seattle combined sewer overflow project.

Plastic Bag Policy Changes

The Council approved an ordinance to extend the ban on single-use plastic bags and change requirements on compost bags. The original ordinance on single-use plastic bags was slated to sunset at the end of this year, but now the requirement will continue as permanent City policy. An additional policy on compost bags will prohibit retail businesses from providing customers with polyethylene or other non-compostable bags that are tinted green or brown. Bags that meet the definition of “compostable” will have to be tinted green or brown and include a “compostable” label. But no bag products may be labeled with terms like “biodegradable,” “degradable,” “decomposable.”

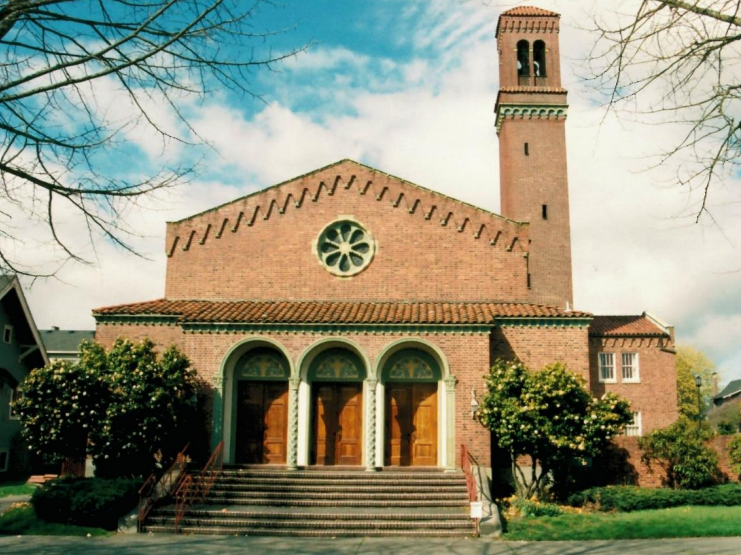

Preserving A Mount Baker Church

The Mount Baker Park Presbyterian Church (3201 Hunter Blvd S) has been designated as a new city landmark. The church was originally built in 1925 and designed by a prominent architecture firm of the time: Albertson, Richardson, and Wilson. The building is particularly noteworthy for its combined usage of the Italianate architectural style–a rare find in Seattle–and the application of terra cotta.

In discussing the Italianate terra cotta design, the Landmarks Preservation Board stated that:

In 1933, Architect Abraham Albertson noted that Italian and Spanish American architectural styles were “not so happy” in Seattle. The use of these styles in Seattle architecture is relatively uncommon. Much of Seattle’s architectural vernacular of the early twentieth century reflects ethnic trends in Seattle’s early demographic makeup, with most of its resident descended or recently arrived from England, Germany and other Northern European countries at this time.

Eclectic architecture, that is, architectural designs that fuse more than one set of stylistic elements, was popular during what is known as “America’s Renaissance (1876-1917). This treatment of historical styles did not completely die out in the 1920s, especially in Seattle. The trend is best reflected in the city’s many apartment buildings designed during this period. Romanesque Revival details, such as those used by Albertson, et al in the design of Mount Baker Park Presbyterian, are sprinkled in a few apartment buildings, and in another of the firm’s buildings of the period, Cornish School of the Arts.

Ecclesiastical architecture, seen in Seattle’s earliest churches until the dissolution of historicist styles in the mid-twentieth century, references traditional programs and styles with European origins. Seattle’s strong Nordic roots were (and thankfully still are, at least in Ballard) evidenced in stave style, wooden frame churches. English Gothic, with its typical long nave, integral towers, often surmounted by spires is illustrated in local neighborhood churches such as Seattle’s First Baptist Church and the small masonry Trinity Episcopal Parish Church on First Hill. In the early 1900s, a number of churches and synagogues employed classical or Byzantine inspired designs popular in civic architecture of the period. Examples of this trend include the First United Methodist Church in downtown Seattle and what was the Fourth Church of Christ Scientist on First Hill (now Town Hall). The use of the traditional basilican plan with simple bell tower rendered in a manner consistent with northern Italian churches of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance was relatively uncommon in religious architecture in Seattle, even during its hay day of architectural eclecticism.

At the turn of the twentieth century, architectural terra cotta gained popularity in Seattle. Cheaper than carved stone, the material was often used on skyscrapers and tall office buildings downtown. The building material, capable of capturing the most fanciful of architectural details, helped shape the identity of Seattle’s commercial district between 1900 and 1930.

Area building material manufacturers aided and advanced the extensive use of terra cotta. Local producers included the Denny Clay Company (first downtown, then in Renton) and the Northern Clay Company. The latter produced the terra cotta work used at Mount Baker Park Presbyterian. Originally located in Auburn, Washington, the Northern Clay Company was purchased by the California firm of Gladding, McBean who merged with the Denny-Renton Clay & Coal Company in 1925, when the church was in its final stages of completion. While it was an independent firm, clay used in terra cotta produced by the Northern Clay Company came from a fifty-acre property along the Green River.

While terra cotta was cheaper than stonework, relative to other building materials, it was still expensive. The costs of production and streamlined, ornament-free architectural trends led to the demise of the terra cotta industry in the 1930s.

Terra cotta use in Seattle churches tends to be restricted to details rather than cladding. Examples of the building material’s use in neighborhood churches include the Gothic tracery of Seattle First Christian (on Broadway) and Seattle First Baptist Church’s (First Hill) window casings and buttress details. The use of terra cotta on Mount Baker Park Presbyterian follows this trend. Colorful decorative work, historically rendered in stone on its Italian antecedents, is articulated in terra cotta on this neighborhood church.

The structure was originally designated the Landmarks Preservation Board on March 3, 2004 and preservation controls were agreed upon between the church and Board on January 6, 2016. The Board cited three primary reasons for designating the church:

(D) It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, or period, or of a method of construction;

(E) It is an outstanding work of a designer or builder; and

(F) Because of its prominence of spatial location, contrasts of siting, age, or scale, it is an easily identifiable visual feature of its neighborhood or the city and contributes to the distinctive quality or identity of such neighborhood or city.

Minor alterations have been made to the structure over time, including a brick patio in 1960, addition of service doors, and changes to windows. Most of the site and structure will be subject to preservation controls, including the site, building exterior, interior of the belfry, and the interior of the church vestibule and sanctuary. Certain exclusions will apply to the church pews, interior casework, and the brick patio.

Living Building Program

The Living Building Challenge Pilot Program can hardly called a pilot program anymore. The City Council adopted an ordinance to update and extend the uber green building program through December 31, 2025 (or when 20 projects been submitted under the provisions, whichever comes first) and codify a new Green Building Standard chapter in the Land Use Code. Developers can voluntarily participate in the programs by providing deep green building techniques and features in exchange for more development allowances.

Changes to the Living Building Challenge code include the following:

- Design review will be required for all Living Building Challenge projects, including those that intend to use existing structures;

- Added building height will no longer require a departure from the Land Use Code, but structural overhangs and architectural encroachments will be added as a listed departure option;

- Projects will have to achieve the Living Building ChallengeSM 3.1 certification set by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI) or the ILFI Living Building ChallengeSM 3.1 Petal Recognition certification and supplementary energy and water standards;

- Up to 15% in extra floor area over the maximum allowed in the underlying zone will be permitted;

- Up to 10 feet in extra height will be allowed in zones with a maximum height of 85 feet or less;

- Up to 20 feet in extra height will be allowed in zones with a maximum height greater than 85 feet;

- Rooftop features may extend above the bonus height if consistent with other regulations;

- The extra floor area and height allowed under the Living Building Challenge will be counted separately and in addition of any other bonus or extra floor area and height otherwise allowed by other provisions in the Land Use Code; and

- Extra floor area and height achieved under the Living Building Challenge will not be subject to the Mandatory Housing Affordability requirements;

- Once a project has been issued a final Certificate of Occupancy, the developer will be required to submit a report prepared by a third party within two years showing showing performance compliance with the approved Living Building Challenge standard. The report will be reviewed by the SDCI for consistency and decide if the project has satisfactorily complied with the Green Building Standard. Failure to provide the report within the two-year period or timely fashion will be subject to daily fines of $500. And to up the ante, a project that fails to show compliance with the approve standard will be subject to a fine equal to 5% of the construction costs.

In addition to extending and modifying the Living Build Challenge, a new chapter was added to create the Green Building Standard. Projects can participate in the alternative green building program by meeting specific requirements to qualify for standard extra floor area and building height allowed in mutli-family residential, commercial and mixed-use, and Downtown zones.

- The Green Building Standard may be somewhat flexible since the Director of the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) is allowed to develop and adopt administrative rules that set the minimum standards and principles. However, the ordinance codifies a standard that requires, at minimum, green building performance at the Gold certification level under LEED (Version 4) or Passive House certification (Passive House Institute Version 9f or Passive House Institute US Version 1.03).

- Structures built on a site on or April 19, 2011 would have to upgraded to the Green Building Standard in addition to any proposed structures in order to qualify for the allowances of the chapter. Structure before that date would not have to be upgraded.

- Once a project has been issued a final Certificate of Occupancy, the developer will be required to submit a report prepared by a third party within 180 showing showing performance compliance with the Green Building Standard. The report will be reviewed by the SDCI for consistency and decide if the project has satisfactorily complied with the Green Building Standard. Failure to provide the report within the 180-day period will be subject to daily fines of $500.

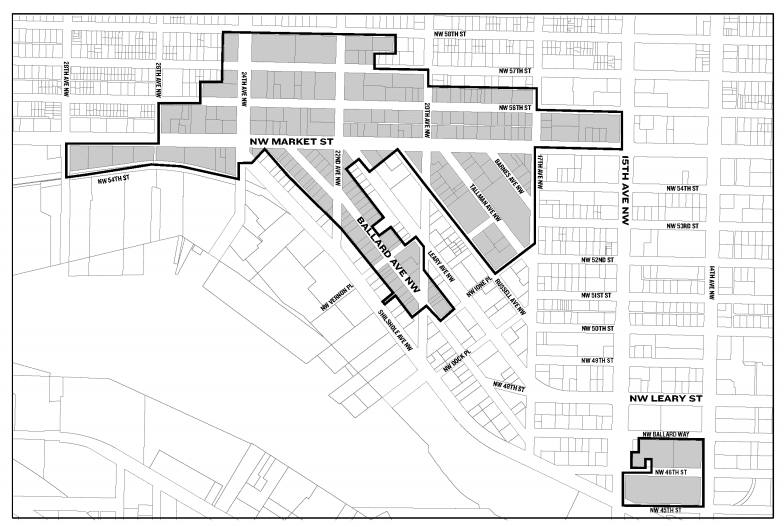

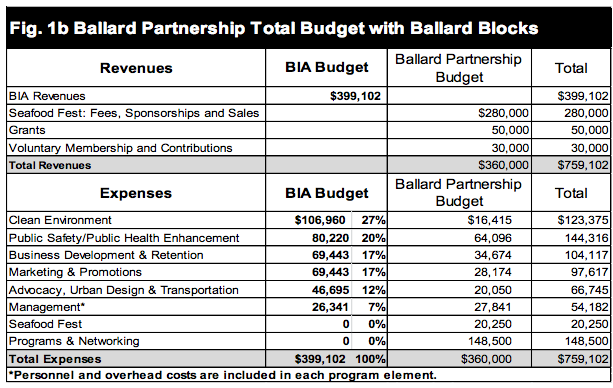

Ballard Business Improvement Area

Ballard is getting a new business improvement area (BIA) to invest in community priorities. Sections of the neighborhood were carved out to support the BIA petition, garnering 60.2% of the vote in favor (just above the minimum of 60% required). Annual property assessments will be billed to property owners in the affected area with proceeds going toward many different neighborhood investments and programs, including some of the following:

- Frequently cleaning streets;

- Maintaining landscaping and investing in street furniture;

- Creating a “Summer Nights In Ballard” program;

- Developing local transportation strategies;

- Initiating a sustainable holiday lighting program; and

- Marketing Ballard businesses and instituting economic development strategies.

Money by the BIA will be matched by the Ballard Partnership to generate more than $759,000 annually. Commercial and multi-family properties will pitch in $90 annually per multi-family unit and valuations of commercial property based upon County-appraised value for building improvements and land. In future years, the rates will increase with inflation, but not to exceed certain maximum increases. The authorized time period for the BIA is seven years, but it could be extended in the future and additional properties could annex into the BIA.

In addition to Ballard, the Council also amended rate payments in the West Seattle Junction Parking and Business Improvement Area for the third time since 1987 by bumping up assessments in three zones of the BIA.

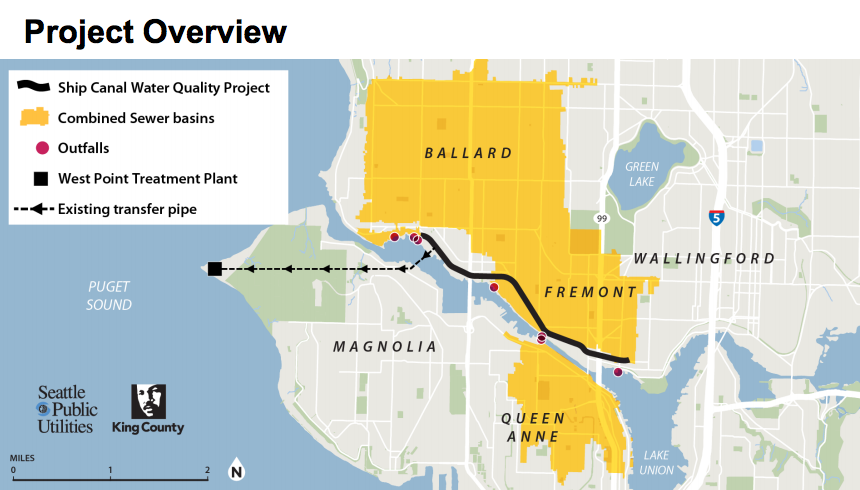

Ballard-Fremont Combined Sewer Overflow Project

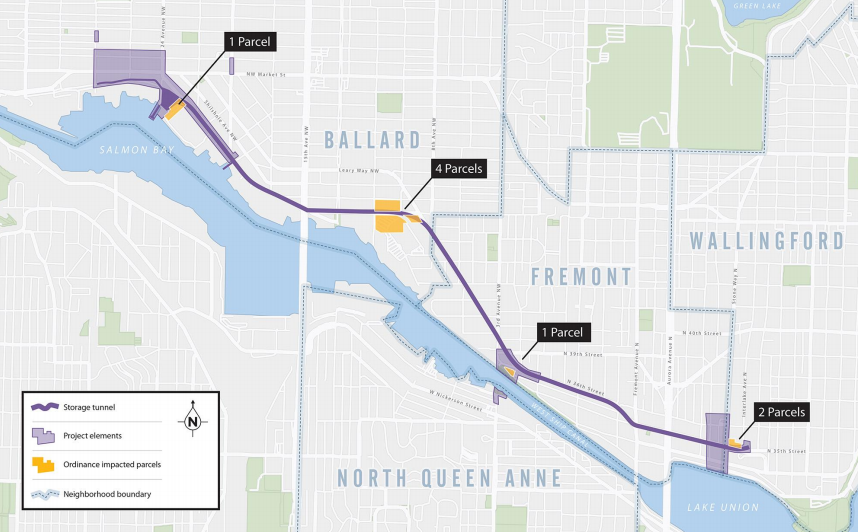

Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) is working with King County to bring the City’s combined sewer overflow (CSO) system into compliance with federal obligations. The joint SPU and King County project will result in a new 2.7-mile tunnel that connects a system of CSO outfall points from Ballard to Fremont, five of which are owned and operated by SPU and a further two that are owned and operated by King County. The SPU’s five outfall points account for 50% of total overflow volume in SPU’s entire system, which is why the project is a major priority. Tying the system together will help send more of the CSO toward the West Point Treatment Plant, reducing overflow events at outfalls, which are supposed to be limited to one event per year. Eventually, new regulator stations will also be constructed at 11th Ave NW and 3rd Ave W by King County, which will treat CSO before it is sent to the adjacent waterbodies.

In the meantime, the tunnels will be constructed mostly along right-of-way hugging the areas closet to the water. A total of eight pieces of private property will need temporary easements for construction activities and may ultimately have to be condemned or purchased by SPU to carry out the work.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.