I am often met with awestruck wonder when people learn I don’t have a car. After all, driving everywhere is the American way. There are too many explanations to keep a good party conversation going, so it boils down to cost and abundance of transportation options. But I don’t get too far before I’m assured I’ll buy a car eventually or I’m declared to be a quixotic car-hating lunatic.

In fact, it’s clear that cars have proven themselves to be far too useful in modern civilization to be reduced to a simple black and white issue. Calls to “ban all cars” do not promote useful dialogue or engender credibility.

For better or for worse, much of our national infrastructure is built on the utility of automobiles. It’s difficult to fight against the fact that most of my food arrives via the interstate highway system. Among many other purposes, vehicles take away my garbage, transport my plumber, deliver my books, and (hopefully never) put out my burning building. Beyond a massive paradigm shift and a complete reconstruction of the built environment, the basics of these arrangements will not change.

So, yes: I’m an urbanist who occasionally drives.

This begs some intriguing questions that this article attempts to answer. Chief among them are whether not owning a car has any important effects on my lifestyle and how much, if any, I’m saving by using car rental services.

To this end, I’ve performed a simple but informative analysis of my own driving habits compared to the cost of car ownership. The objectives are to inform contemporary transportation and parking policy debates and help fellow urbanites determine whether they really need to own a vehicle.

Analysis Overview

To start, I need a baseline cost of personal car ownership, which obviously varies widely. Depreciation rates, maintenance needs, insurance costs, parking, fuel prices, and driving distance all differ for individuals and their vehicle type. But a few sources like the American Automobile Association and Kelly Blue Book offer a similar ballpark average for newer cars nationwide: about $8,500 per year. That’s across all types of communities in America, so for this analysis I’ve rounded it up to a simple $10,000 to represent an urban area like Seattle with higher fuel costs, paid parking, slower commutes, bumpy roads, and many voter-approved vehicle taxes.

A related statistic: personal cars are unused and parked for 95% of their existence. Compared to the value of new cars (in the range of $20,000 to $30,000 or more) we sure don’t use them much.

The numbers above only reflect the individual costs. The analysis will not account for the unpriced externalaties of air and water pollution, planetary climate change, congestion, urban sprawl, public health, and traffic injuries and deaths. I and many other experts have written plenty about those problems already and the research is freely available. For this analysis, I’m only focusing on one thing that greatly influences people’s lifestyle choices: their wallet.

My analysis starts by accounting only for long-term rental trips–that is, trips that are most similar to the benefits of car ownership: flexibility in schedule, predictability in parking location, and opportunity for spontaneity in route and destination. Therefore, I did not include car2go and ReachNow trips because there was no guarantee of a vehicle being reasonably available. I also excluded Lyft trips because most of them could have been replaced by transit, I don’t use it to travel outside the city, and in many situations I was not in a condition to drive (happy new year!).

What it comes down to is mostly my Zipcar trips. Zipcar is an American car-sharing company founded in 2000 and based in Boston. It was bought by the traditional rental company Avis Budget Group in 2013. The company has one million members and 12,000 vehicles in over 500 cities around the world (Autoblog reports membership is growing a massive 10 percent per year).

The core of the Zipcar service is simple: cars are spread throughout a city and have a dedicated parking spot on the street or a private lot, and can be rented on an hourly or daily basis straight from members’ computer or phone. Zipcar charges an annual fee for members, provides fuel and insurance as part of the rental cost, and offers 180 free miles per day. This has advantages over larger companies like Hertz and National which have centralized facilities, onerous contracts, and require drivers to purchase their own fuel.

Zipcar has recently offered a point-to-point service to compete with car2go, and services like ReachNow have started to offer all-day rentals, but so far no other player in the industry is effectively competing with Zipcar for long-term rentals with a variety of vehicle types (at least to my knowledge in the United States).

I first joined Zipcar in 2012 while in college in a small town. My roommate with a car, who I often hitched a ride with, had moved out and I needed an alternative for grocery shopping. Lo and behold, Zipcar arrived on campus about the same time. So, there is over five years of data to draw from. But since I’m most interested in how car-sharing affects urban areas, which abound in transportation choices, I’ve limited the analysis to my tenure in Seattle.

The scope is further narrowed to my two full calendar years living in Seattle as a full-time employee, 2016 and 2017; when I was a low-income grad student 2013-2015 I made different transportation choices. In addition, I only began collecting detailed notes in early 2017, so the older data is not reliable due to spotty or nonexistent receipt records.

The Data

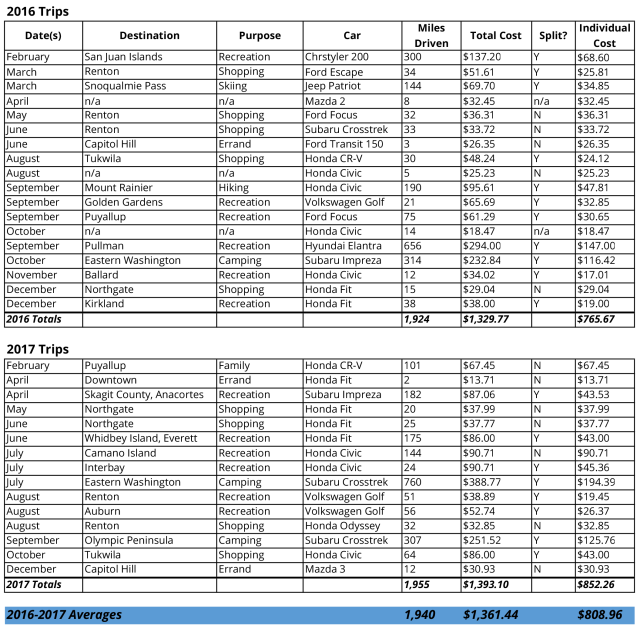

Now, the data you’re looking for. Details on trip date, destination, and purpose have been generalized for privacy. See the Notes section at the bottom of this post for details on exclusions and other circumstances.

I averaged about 2,000 miles and 16 trips per year (1.25 per month). I burned approximately 53 gallons of gas per year, resulting in annual carbon emissions of one-half ton. The rental costs averaged about $800 per year, which is less than 50 cents per mile.

The Results

The $10,000 annual car ownership cost established above is based on an average 15,000 miles per year but is largely locked in by depreciation, insurance, taxes, and financing. However, part of it is variable by miles driven.

Accounting for all of this and sparing the dry calculations, at a minimum I’m saving an astounding $8,000 annually. This is remarkably consistent with the savings Zipcar reports from its membership.

$8,000 is a huge a portion of my income. If I wanted to own a car but save the same amount elsewhere in the budget I’d need to string out my student loan debt many more years or cut my rent in half, which is nigh-impossible in the Seattle housing market. Owning a car would doubtlessly be a net financial loss–not to mention the effects on my carbon footprint and chance of serious injury.

Would I have driven more had I owned a vehicle, therefore affecting my conclusion? Almost certainly, but it’s impossible to determine to what degree the difference would be. In the city I will always prefer walking, bicycling, and taking transit to car-based transportation not only for environmental reasons but also the physical and mental health benefits.

Will my needs and preferences change as I age and think about having a family? Maybe, but with what I know it seems doubtful until something major changes. I can’t see myself living in the type of bland and unwalkable suburban community where car ownership is a necessity for daily life. And in the city, the constantly expanding transit options, growing traffic congestion, greater cost of fuel and parking, and autonomous cars on the horizon all make car ownership seem increasingly like a liability to be avoided.

Perhaps the most important question: Have I enjoyed the same types of experiences that many Seattleities use to excuse themselves for owning a car? That is, going to the mountains or the ocean and taking long road trips across the state?

Unequivocally, yes! I’ve ventured beyond the city many times for a variety of reasons–from shopping and visiting friends to exploring the outdoors–and feel I have lived just as wholesome a life as anyone else. I’ve camped among the majestic Olympic Mountains, crisscrossed the fertile Columbia Plateau, taken selfies with Skagit County tulips, and yes, went to IKEA. And I’ve done it for a lot less money, less impact on the environment, and greater peace of mind than otherwise.

With regards to the post title, if I’m driving am I really free of cars? Yes, because this is about being free of car ownership. In a country where two and three car households are the norm, and owning only one car is considered living car-light, I’d argue owning zero cars but leveraging their utility for certain trips fits within the definition of “car-free”. Just make sure not to confuse it with “car-less”.

Going Forward

According to Zipcar, a “Transportation Research Board/National Academy of Sciences study finds each shared car takes about 13 private cars off the road”. The expansion and diversification of car-sharing services has massive implications for the built environment and ecological resiliency. More access to this transportation option–along with more robust opportunities to walk, bike, and ride transit–will allow for more compact and livable communities.

Cities can shape this type of future by prioritizing the availability of shared cars on public streets and reducing or eliminating minimum parking requirements, especially for residential buildings in established neighborhoods. They can also get creative where parking is built: In Vancouver, B.C., developers may substitute one long-term shared car parking spaces for five private parking spaces.

Cities can also help promote shared car services and educate the public on the benefits of living car-free by presenting the financial, environmental, and health data that supports it. It’s not for everyone; some long commutes, job requirements, and family obligations simply aren’t practical on the bus or train. But if even a fraction of a city’s population voluntarily adopts a car-free transportation style the positive impacts can be many, among them lower emissions, better air quality, safer streets, and less expensive housing.

If you live in a transit-rich and walkable community with car-sharing services and you consider yourself a steward of the environment, I encourage you to think about ditching your car. Not only will you spend less time searching for a parking spot, it’ll put money in your pocket and will help make your community and our planet a healthier and happier place.

I’ll be updating this article with new data annually. Feel free to ping me with questions about living car-free.

Notes:

- The data includes three traditional rentals through Enterprise.

- I’ve excluded the considerable number of business trips I’ve done with Zipcar. My employer agreed to reimburse the rental fees (and occasional tolls) when I demonstrated the benefits over traditional car rentals. The arrangement is roughly equivalent to being compensated for personal car use.

- I’ve also excluded personal trips that originated outside of Seattle, such as when I used Zipcar for sightseeing during trips to Denver and Los Angeles.

- To reflect true individual costs I’ve noted where the trip expenses were split. Some of the trips go back so far I can’t find a record of the trip purpose and who I was traveling with, so in those cases I assumed the costs were borne only by me.

This article is a cross-post from The Northwest Urbanist.

Scott Bonjukian has degrees in architecture and planning, and his many interests include neighborhood design, public space and streets, transit systems, pedestrian and bicycle planning, local politics, and natural resource protection. He cross-posts from The Northwest Urbanist and leads the Seattle Lid I-5 effort. He served on The Urbanist board from 2015 to 2018.