“Missing middle” housing types weren’t a focus of a recent report on middle-income housing.

On January 22, 2020, Mayor Jenny Durkan took receipt of the final report from the Affordable Middle-Income Advisory Council. According to the press release, the report is a series of “suggested tools to help create more opportunities for homeownership, bring more housing online faster, and increase housing options in neighborhoods throughout the City.”

In reality, these tools are unlikely to kickstart the transformation Seattle’s rent-burdened masses are hoping for. The bulk of the report is about making it easier to keep doing what we’re already doing: depend upon big entities using complex financing to slice up properties and exclude everyone else from neighborhoods. The report supposes that there is a mythical lake of money that can bestow housing on worthy projects. However, to paraphrase Monty Python, social organizations lying in money pools distributing elaborate financial instruments is no way to build a decade of backlogged housing.

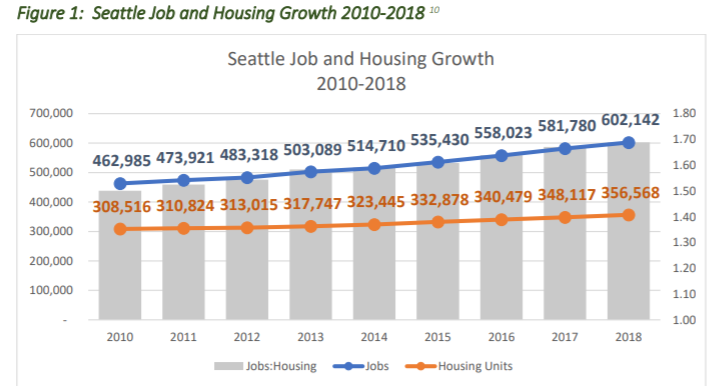

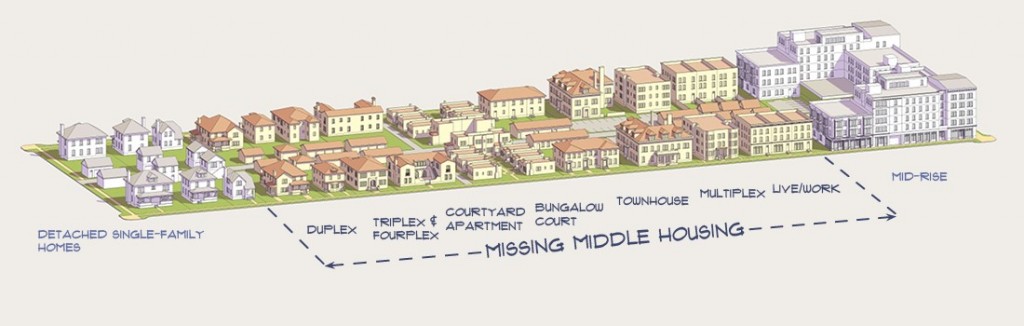

Which is a shame because we need a past decade and a future decade of new homes. Middle-income affordability is tied to the concept of “missing middle” housing, which the report mentions a couple of times. Popularized by the Opticos Design group, the category of “middle” covers the multi-unit plexes, courtyard apartments, and townhomes–buildings of a similar scale to the detached houses dominating suburbia. Middle housing gently increases the number of homes in a neighborhood while being less expensive to build and operate than large apartment buildings. It’s missing because we just don’t build it anymore, particularly in Seattle. And not much in this report is geared toward jumpstarting missing middle construction.

The Highest Impact

Mayor Durkan took the three highlights of the report’s Executive Summary and boosted them as high-impact recommendations.

- Reduce costs of building housing by promoting partnerships with private sector investors and philanthropic dollars for innovative real estate financing.

- Advocating to the State to extend the Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program beyond 12 years of affordability.

- Reduce construction costs and bring new homes online as quickly as possible by reforming permitting practices.

These floated to the top from the 40 smaller recommendations that the committee developed in its year of work. And they are fine for what they are: exact and limited responses to the five charges that were laid out at the Committee’s first meeting:

- Identify the next steps necessary to increase housing choices affordable to middle-income individuals and families.

- Provide a compilation of middle-income housing strategies that could be advanced through new investment financing.

- Deliver recommendations on the architecture of potential new housing investment fund(s).

- Conduct outreach to neighborhoods, community and housing advocates to inform the work of the committee.

- Identify the steps required to attract equitable development investments in Seattle Opportunity Zones.

None of this says “build a house.” Three of these five charges involved financing, so there is little surprise when the recommendations are about lowering the barriers to investment. When more than half of the committee members come from finance or large developers, it’s pretty obvious which way the recommendations are going to fall.

The call to reform the permitting process is also pretty obvious. Twice the report drops “new housing must conform to more than 4,000 pages of regulation” without saying if it’s zoning rules, building code, federal regulations, or all of the above. Most of the recommendations are not about the actual codes, but the time it takes for projects to move through approvals.

Process reform comes under the heading of “Align City Organization to Support Housing Production.” The report suggests that such reforms could save projects enough money to lower rents by 10% or sale prices by 12%. It leads us to ask, on what kind of units are the prices being lowered?

Typical Prototypical

The report examines three “development prototypes” to see how much the proposed regulatory changes would impact development. The three prototypes are a 150-unit apartment building, a 150-unit condominium building, and a fourplex of for-sale townhouses.

The committee broke down the costs associated with constructing each of these prototypes, then penciled out how the committee’s recommendations would save each one. Streamlining permits would save the townhouses $41,207 per house. Reducing infrastructure costs would save the apartments $51 per month per unit.

But there are only three prototypes, two if you consider that the apartment and condo buildings are exactly the same but for selling or renting the units. These are not small developments. In essence, the committee suggests providing middle-income housing by making 150-unit buildings slightly more cost-efficient. If that doesn’t work, there’s not much left.

Building these prototype homes depends on an enormous outlay of money. The multi-family prototypes cost more than $30 million to build on $8.4 million worth of land. The townhouses cost $1.5 million to build after buying $800,000 worth of land. These developments are anything but “middle”. They are only available as large investments to large investors. Saving 10%-12% on any of these is a lot of money, more than most people have to play the market.

The committee tries to assuage this exclusivity. Recommendation 1.02 calls to “Broaden Pool of Social Impact Investors,” noting “Seattle has many residents willing to invest a portion of their net worth for a positive community and social impact on our region’s housing crisis. Several local nonprofits have secured social impact capital from their donors to build low-income affordable housing, and some have embarked on raising funds for housing through crowdfunding or an investor portal. But social impact investing has not yet reached the scale necessary to address the scope of the issue.”

The report is about pooling money for large investments. Reduce registration requirements for social investors. Create federal tax incentives. Partner with institutions. Boost Opportunity Zones. Swing for the fences.There are no numbers to support that this pool of money exists or is large enough to build a substantial number of homes. The number of potential investors is vanishingly small and already being tapped to support everything from the city’s art museums to the local PTA.

The social impact investments still get pooled and filtered through organizations and developers to build multi-family, subject to the same limitations on available land and zoning that are preventing housing from being built right now. We cannot build townhouses or multi family in most of this city, and the report doesn’t touch that.

Where the committee wrestled with zoning, they did so attenuated terms. “The City should evaluate” or “the City should encourage.” Where the report suggests zoning changes, it picks areas that already allow for density, hides density on irregular lots, or worries about the “character” of structures. Only where it talks about areas around light rail and high-frequency transit does the report offer real support for increasing zoning.

Little Room for Error

The Middle-Income Housing Advisory Council was charged with finding ways to create`housing choices for Seattle’s middle-income owners. But from the prototypes, you get to choose between a big building or group of townhouses. The neighborhoods are still limited to the same ones that already support those types of houses.

From the financing side, there is only one choice: a big pool of money. The goal of that big pool of money is to knock down the price of building these two flavors of housing. If these proposed reforms don’t loosen up that big pool of money, then we are looking at another decade of excluding middle-income households from much of Seattle. We’d have swung for the fences and missed.

It all ignores one of the most important lines of the City’s Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) Environmental Impact Statement : “Decreasing housing costs is the most commonly discussed method of increasing housing affordability, but increasing income can achieve the same effect.” Raising people’s ability to buy or rent is equal to cutting costs.

Contrast that to the middle-income report’s pools of money and investment portfolios. There are few places where the middle-income report attempts to hamhandedly increase buying power. Recommendation 2.01 helps workers buy homes by engaging employers to create subsidies. Cooperative housing and congregate housing are mentioned, without a context to the sizes needed to make these feasible. A recommendation to train more construction workers is made to lower the prices on buildings, not giving people living wage jobs. It’s all from the top. Knock the costs off of very expensive projects and hope it trickles down.

The Difficult Gap

So what does the opposite of trickle-down look like? What could ascending affordability mean? The hint comes from the source of the concept. Accessory dwelling units–adding additional units to existing homes–helps raise income while putting people into homes. The process does not need to divide up the property into tiny lots. Costs of ownership are assumed by choice. The landlord has a house and additional income.

The committee and Mayor Durkan recognize the importance of ADUs through their support of the ADU program. As the committee report notes, financing ADU construction can stabilize existing homeowners and build smaller-scale homes. Mayor Durkan has launched a pilot that provides low-cost loans to make sure the benefits of ADUs are not limited to wealthy white homeowners.

Unfortunately, the limits of the ADU program are burned into this report. The prototype fourplex is strictly four for-sale townhomes because it’s above the ADU program’s allowable three total dwelling units per lot. Mention of townhouses, duplexes, triplexes and cottages are reserved for “less expensive homeownership,” not rental. You either get an apartment in a large building or you have to buy something. We just have to wait for all these investors to get these buildings built.

By relying on big pools of money to solve the problem, there’s no mention of little pools of money. There is no model for building a triplex financed by a homeowner mortgage and renting out two of the floors. There’s nothing about skipping the subdivision of the prototype townhouses (at significant cost savings) and having a fourplex condominium. There’s no mention of building a cottage development with your friends.

Missing middle housing is not just a particular design of a building. It is fitting the right house and right ownership into the correct city. Currently, the only middle between renting an apartment and owning an apartment tower is buying a single-family house.

Realistically, that wide chasm between renter and land baron should be filled with tons of alternatives. Any report for middle-income housing must at least recognize that people split leases, pull in tenants, and sublet just to stay in their homes. A really insightful report would notice the informal, familial, or convenient arrangements that house many of our neighbors. Allowing this variety to bloom allows more people to live in Seattle. Supporting homes built by these arrangements will correct our housing deficit faster and more equitably than waiting for a puddle of money to form.

These arrangements can happen thousands of times across the whole city, taking the pressure off of any single program. The most recommendations in this report are “monitor this program to see if it worked” with continuation and funding at stake. Expecting any single program to pull the city out of its housing deficit is unreasonable. By increasing the opportunities for many people to come up with interesting new things, the margin for error decreases and the likelihood of success goes way up. We’re not just swinging for the fences anymore. Bonus housing will come from getting bloated programs, exclusionary zoning, and basic prejudices out of the way.

Cynically, one could point out that you can’t have mayoral ribbon cuttings at thousands of little projects, so it makes sense for the administration to push the big ticket items. And big projects are necessary. The climate crisis demands we rise to the occasion and think big. Our transit investments should unlock areas for vibrant, dense development. We will experiment with cooperative living and social investment every chance we get.

But we face the truth that Seattle couldn’t get more than a couple hundred homes approved on an abandoned military base. While Fort Lawton may have changed some things, reading any post about new buildings in the city shows how feast or famine the process can be.

The best outcome is all of the above–big projects, small investments, revised zoning, equitable transit–with the highest success coming from many diverse solutions. And we wouldn’t be left on the side of a lake, waiting for a strange woman to throw us a sword.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.