How did we get here?

Over this series of articles, I am laying out an argument that Seattle should mix industrial uses in our residential and commercial neighborhoods. A long history of exclusion keeps interesting and useful things out of our communities, an absolute loss for building a vibrant and vital city. Now is the time to change this because the lines have disappeared between the places we work, create, build, and live. Right now, every neighborhood is mixed use. Read part one of the series here.

Today, we’re talking about how this exclusion was created. From terrible court decisions to regional politics, a long history has lead up to excluding industrial uses in various ways. We’re going to look at three parts of this history: the exclusive foundations of zoning, the attenuated zoning maps, and the exception to both.

The cornerstone of zoning authority in the United States is a United States Supreme Court case called Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. In that case, the court was asked to decide if a municipality had the power to divide its territory into sections and restrict particular uses in each section. The case was brought by a property owner who said that such restrictions reduced the value of his property and deprived him of liberty and property without due process of law.

Euclid, Ohio is a railroad suburb of Cleveland on the shores of Lake Erie. In the 1920’s when this case was brought, it had about 10,000 people (today, it’s 47,000). Concerned that they would be overwhelmed by industrial sprawl from The Cleve, Euclid adopted a zoning ordinance in 1922. The court upheld the ordinance, and we still contend with its effects today.

The upshot of the decision is that municipalities may use their police power to enforce zoning. In the court’s view, laws that designate limits on use and building size are legitimate government purposes. The city gets the benefit of a doubt that zoning is rationally related to the purposes for which it is established.

The court went further in two ways. First, the court held that single-family residential was virtually sacrosanct. The holding supports sectioning off residential districts from not just industry, but any type of business. It found acceptable to exclude “apartment houses, business houses, retail stores and shops, and other like establishments” from residential districts. That the court chose to section off apartment houses from detached homes is not an error. Their view on the matter is very clear. “Very often the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.” All zoning flows from protecting the single-family home.

Second, to preserve these residential districts, the court allowed use regulations to be drawn large. Normally, a law can be challenged for vagueness. Our government is one of enumerated powers, and laws that are not explicit in their requirements and definitions are frequently struck down.

But here, the court didn’t just uphold the ability to create industrial districts. It held that these districts could be created with a broad margin to make sure to catch all the industries. “It may thereby happen that not only offensive or dangerous industries will be excluded, but those which are neither offensive nor dangerous will share the same fate.” The court was fine drawing a bright line around exclusive residential districts, and then simply labeling the rest of the map as “everything else.”

The Maps

Based on Euclid, every zoning ordinance comes with two parts: the use controls and the zoning map. Just as use controls have excluded everything but residential homes from most of the city, there are many places where the development and execution of the zoning map is also a tool of exclusion.

Maps are used to exclude by creating artificial hierarchies. Why do we even think about residential or commercial as being “higher” or “better” uses? It’s because the same list of preferences–pristine residential, parasitic apartments, and pollution spewing industry–that Justice Sutherland wrote out in Euclid is embedded into our maps.

This is easiest to spot at a higher level. Regional governance structures like the Puget Sound Regional Council coordinate planning among 80 different local governments to manage conformance with the Growth Management Act and the distribution of federal transportation money. To do that, they have to rank the priorities and balance them between all these squabbling jurisdictions. In the name of ranking priorities, the regional framework also continues the policies of exclusion.

PSRC hierarchies start with focusing development in tiers of cities. Metropolitan Cities (Bellevue, Bremerton, Everett, Seattle, and Tacoma) are called upon to accommodate 36% of the regional population growth and 44% of the regional employment growth over the next 30 years. Next step are Core Cities like Auburn, Renton, and Federal Way set to absorb 28% of the regional growth. Then there are Larger Cities, Smaller Cities, Agricultural Land, and Natural Resource Land.

To borrow Douglas Adams, these hierarchies allow for the creation of a Somebody Else’s Problem field. If your town can avoid designation for growth, all the growth becomes somebody else’s problem. The 42 small cities and towns in the region are designated to absorb a combined 6% of the region’s population growth. This constraint makes sense for rural Index and Black Diamond. The same hierarchy allows Yarrow Point, Hunts Point, Medina and Clyde Hill–towns literally on the highway between Seattle and Bellevue–to exclude development and increased population.

There is another layer to hierarchy. Within each of the Metropolitan Cities is located a Regional Growth Center. Seattle has six–Northgate, University District, South Lake Union, Uptown Queen Anne, Seattle Downtown, and First Hill/Capital Hill as well as two Manufacturing Centers: Duwamish and Interbay. Designating hierarchy within the hierarchy allows Somebody Else’s Problem to repeat itself inside the city.

Letting parts of the city off the hook for development allows the base layer of Seattle’s zoning map to remain single-family detached residential zoning. Though the city is designated a Metropolitan City to absorb growth, 75% of the city’s buildable land is zoned single-family detached. From the time that Seattle adopted its new zoning ordinance in 1957, waves of rezonings nibbled away at allowable duplexes and triplexes, reducing the types of homes allowed to the largest and most expensive. Since the city adopted its Urban Villages Plan in the 1994, the city has grown by more than 220,000 people. Nearly all of those people have moved into the few Urban Villages, allowing some of the neighborhoods with exclusively single-family zoning to see population decreases. Again, this is all within the top tier Metropolitan City.

Overemphasis on residential could be mitigated, except we have also screwed up the shape of the remaining zones. The gerrymandered scribble is most startling with commercial zones. Throughout the city, there are only three large commercial districts: University Village, Aurora Avenue north of 115th St, and the Seattle Joint Task Force facility off Meyers Way in South Seattle. (Places like Northgate Mall are zoned Mixed Use.) Everywhere else, commercial zones are limited to one parcel on each side of a road. This is because we allow zones to be established based on lot lines rather than fill entire blocks or follow natural breaks.

Tailoring zones to lot lines has made every other commercial zone in the city less than a block deep. We end up with these thin rustic crucifix at major intersections. Holman Road and Greenwood Ave North is a great terrible example. All of the commercially zoned properties are single lots following the main streets. They do not cross alleyways or create buildable lots of any significance. The exception is a single commercial space on the west side of the intersection that extends from Holman Road to 100th Place. This is a single parcel with a long-standing QFC, and either end of the block is zoned for multi-family.

We do not create commercial zones that support anything except a very small, likely automobile-centric, commercial uses. Then we further inhibit development of these zones by requiring buffering and setbacks to “protect” the neighboring residential uses. For projects located at the edge of different zones, Seattle’s Design Guidelines call for “a step in perceived height, bulk and scale between the anticipated development potential of the adjacent zone and the proposed development.” It includes five factors to consider, including distances between structures, type of separation, and adjacencies to different open spaces. None of the factors mention considering the extreme narrowness of the underlying zoning.

If there are no parcels that are large enough to support a new grocery store in a commercial area, that necessarily pushes those uses to more accommodating zones. This means that land set aside for industrial uses, but conveniently located to growing neighborhoods, is ripe for de-industrialization.

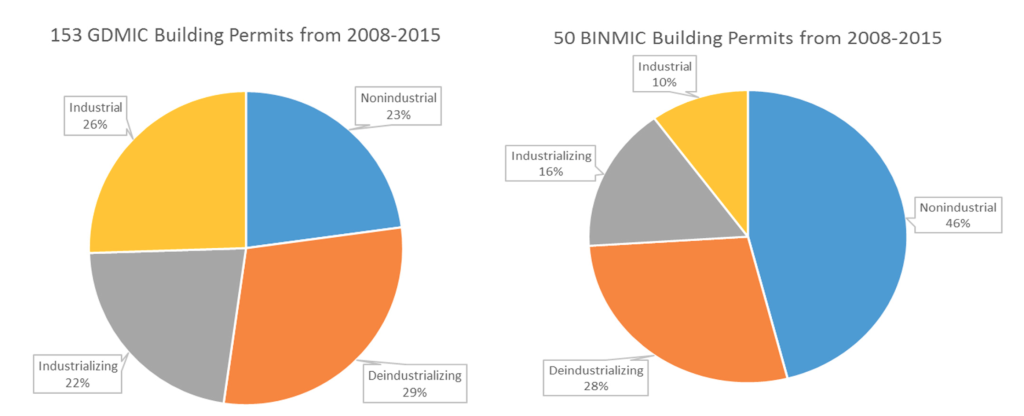

We can see the trend in the permits issued in the industrial areas. Between 2008 and 2015, more than half of the permits issued in the Greater Duwamish Manufacturing Industrial Center (GDMIC) were for uses that were non-industrial or converting from industrial to non-industrial uses. Within the Ballard-Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center (BINMIC) over the same period, almost three quarters of permits were non- or de-industrializing.

We often focus on the impacts of industrial uses on commercial and residential property. However, as pointed out in the 2015 Industrial Lands Analysis from the Puget Sound Regional Council, negative impacts flow the other direction too. These can include traffic congestion, increasing land values and rents, and complaints about noise and odors that lead to nuisance investigations. Our industrial zones are meaningless when they become a catch-all for the uses squeezed out of other areas.

Zoning has us continually thinking about the negative impacts of industrial uses on the better, higher uses. But even defining the map in terms of better and higher shows how imbedded in our minds the hierarchy and exclusion have become.

The Exception

Every rule has an exception, and the sanctity of residential zoning is no different. Many jurisdictions have provisions for “home occupations”–nonresidential uses that are “incidental and secondary to the use of a dwelling for residential purposes and does not change the character of the dwelling.”

Seattle permits home occupations in all zones that allow residences. To qualify as a home occupation, the non-residential use must be “clearly incidental to the use of the dwelling as a dwelling.” There are limitations on deliveries, parking, signage, and client visits. The non-residential use is limited to 500 square feet of the dwelling. Some things that fall into the category of home occupations are bed and breakfasts and child care.

This current flexibility has not always been the case. In a 1953 report, the American Planning Association surveyed zoning laws about home occupations. They found, “those occupations which customarily have been given approval when conducted in the home are the professions, chiefly doctors and lawyers, and certain feminine occupations such as dressmaking and sewing.”

While our current code doesn’t couch it in quite as misogynistic terms, that division is still there. From the Seattle Residential Code, under strict space constraints a residential use may include: “offices, mercantile, food preparation for off-site consumption, personal care salons and similar uses which are conducted primarily by the occupants of the dwelling unit and are secondary to the use of the unit for dwelling purposes.”

The exception for Home Occupations illustrates two things about the formulation of zoning–it came at the peak of industrialization and it was crafted by the mechanically minded experts steeped in the wealth of the time. The early 20th century was the culmination of all the rail building and slaughterhouses of the post-Civil War era. Zoning laws were crafted with those types of factories in mind. A third of the workforce was in manufacturing or construction jobs. Progressive activists chronicled the crowded living and dangerous working conditions.

And yet, wealth was pouring upwards to the upper class. Upton Sinclair described the division: “All day long this man would toil thus, his whole being centered upon the purpose of making twenty-three instead of twenty-two and a half cents an hour; and then his product would be reckoned up by the census taker, and jubilant captains of industry would boast of it in their banquet halls, telling how our workers are nearly twice as efficient as those of any other country.”

The experts developing zoning didn’t come from the classes working in those factories or living in those tenements. They were designers working for those captains of industry and other exalted occupations like lawyers and doctors that could work from home. The exceptions carved out by home occupations weren’t about flexibility in zoning. The exceptions show the absolute primacy of exclusion in zoning. Zoning is a Great Gatsby solution to the The Jungle, wealth deciding that the best way to deal with the worst of industrialization is to section it off.

The history of zoning is about creating exclusionary rules then reinforcing them with mapped hierarchies. It has worked exactly as expected. As Tim Parham, chair of the Planning Commission said on the release of the commission’s Neighborhoods For All report, “Our current approach to zoning has created a bifurcated city, where two-thirds of residential land is off limits to all but those with the highest incomes.”

While the Planning Commission and Seattle City Council have taken important steps in knocking down the most egregious exclusions, we’re still working under Jazz Age assumptions codified as law and mapped onto the land. Seattle’s last smoking steel foundry is now a Fred Meyers and its sprawling gas refinery is a waterfront park. Our residential zones should be ready for similar changes.

As our current quarantined teleworking shows, the strict square-foot limits and antiquated list of occupations and “secondary to the use of the unit for dwelling purposes” are done. Our use laws and zoning map must follow suit.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.