Cohousing offers ways to stay connected during the Covid pandemic that city planners, architects, and community organizers can learn from.

This spring, while people across Washington State and beyond were really beginning to understand what it means to be “socially distant” for a sustained period of time, some of the residents of Puget Ridge Cohousing in West Seattle began a new tradition of meeting daily for lunch. Shared meals are a common occurrence at Puget Ridge, and also a treasured staple of cohousing life in general, but with the Covid virus wielding its way across the globe, all community meals were canceled- meaning the residents had to get creative about maintaining social connections while safeguarding their community’s safety.

With a little community organizing, some of the residents created a “community lunch pod” by scheduling to eat lunch on their private porches at the same time each day. The porches, which each look out on a community walking path and central green, are situated at least six feet apart, ensuring safety as residents chatted and enjoyed a break from remote work.

For Heather Cole, one of Puget Ridge’s newer community members, the community lunch pod offered a welcome break from the challenge of sharing her 700-square-foot home with her husband, who was also telecommuting full-time. But while juggling Zoom calls from the bedroom, porch, or even bathroom has not been easy, she has had no regrets about moving in to cohousing prior to the pandemic.

“When I compare what we have to our friends who live in condos, I am struck by the unique elements of this place that facilitate community,” Cole said.

This style of cohousing originated in Denmark in the 1970s as bofællesskaber, and it offers a balance of private and shared spaces not commonly found in housing design. Unlike co-living, which emphasizes shared residences, cohousing members live in private residences, which can range from studio apartments to single family dwellings. Community building is facilitated by access to common facilities, such as a central kitchen, dining hall, and community gardens. Shared activities, including community meals, are woven into fabric of daily life and residents also participate in community governance.

Cohousing is found all over the world in areas that range from rural to urban. It is also on the rise. While the number of people who live in cohousing remains relatively small, the Cohousing Association of the United States expects the number of cohousing developments across the US to double in the new few years.

But in the era of Covid-19, how has the cohousing model held up? Have the same community building principles that decrease social isolation led to increased risk for transmission of the virus? Will people remain interested in a lifestyle that often includes accepting smaller living spaces in order to gain access to shared community amenities?

It might come as a surprise to some, but the cohousing model, with its blend of private and shared spaces, has held up quite well during the epidemic. While some of the cohousing residents I spoke with admitted that they probably would not have chosen to move into a cohousing community during a pandemic, all of them expressed that living in cohousing has greatly improved their lives under Covid.

“Living in cohousing is a significant destressor in life, including during Covid,” said Diane Hetrick, another Puget Ridge Cohousing resident. “We have access to so much shared support.”

In fact, the cohousing model might offer some valuable lessons for city planners, architects, and community organizers grappling with the challenges of urban life under Covid. These same lessons also provide a tutorial in resilience that could continue to be useful after the pandemic ends.

Maintain physical distance, not social distance

We have heard a lot about the need for social distancing in recent months as the Covid pandemic continues the health of people across the world, but according to experts on psychological health, what people really need to do in the face of Covid-19 is remain physically distant. Social connection, which can occur online, over the phone, or in an outdoor area with six feet of separation, remains as vital to people’s health and well-being as ever.

Human beings are hardwired for social connection. In fact, studies have shown that social isolation as a predictor of mortality is comparable to that of well-documented clinical risk factors that increase mortality like smoking, obesity, elevated blood pressure, and high cholesterol levels.

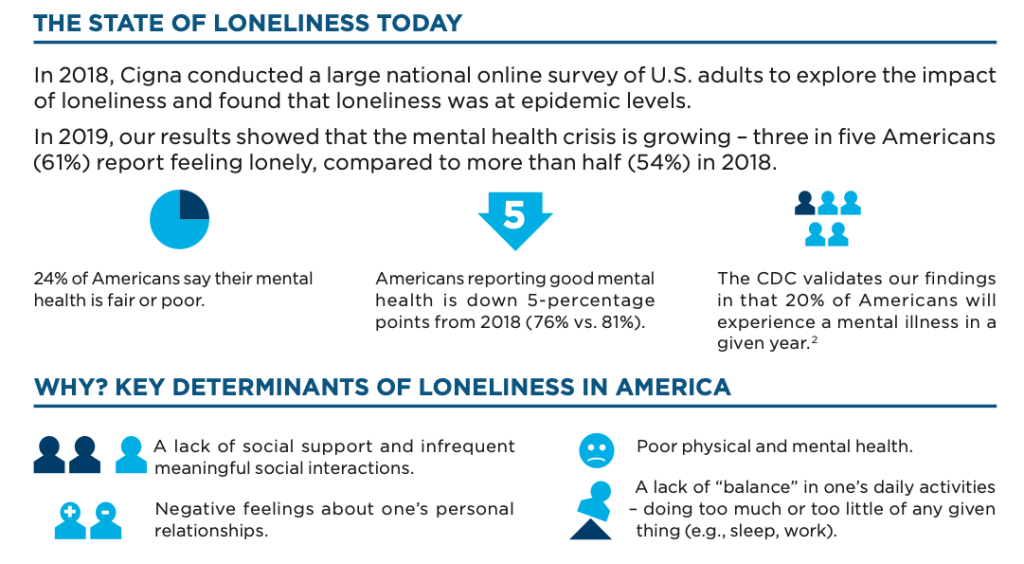

Alarmingly, even before the spread of Covid necessitated social distancing, loneliness and social isolation were already at record levels in American society. In January 2020, health insurance company Cigna released a report showing that roughly three in five American adults identified as lonely. This represented a 7% increase over figures published in 2018.

While a study conducted by the American Psychological Association (APA) found that levels of loneliness did not increase during the implementation of social distancing measures, experts fear that the numbers will surge as the duration of social distancing measures drags on. People who live alone and who suffer from chronic health conditions were already at especially high risk of social isolation before the Covid epidemic and may be particularly vulnerable to its effects moving forward.

Ensuring that neighborhoods and housing developments contain shared spaces that facilitate engagement while allowing for physical distancing will be key for maintaining people’s health in a Covid city. Seattle’s move to open Stay Healthy Streets to pedestrians and cyclists has represented a positive move in this direction, and opening some streets to dining would go even further to provide people to have safe areas to recreate and socialize while enjoying city life. But to serve a city of 760,000 residents, the scale of these programs will have to be significant.

In terms of housing design, Covid has shown us how equipping housing with a balcony can greatly improve residents lives by providing much needed private access to outdoor space in dense city settings.

Balconies can also facilitate “socially distant” interactions. Capitol Hill Urban Cohousing, designed by Schemata architect Grace Kim who lives there with her family, features private balconies encircling a central shared courtyard. During Covid, the balconies have enabled residents to engage in community activities like bingo and even a birthday celebration while maintaining physical distancing.

“The Covid-quarantine period has demonstrated the need for personal outdoor space,” Kim said. “Like porches, balconies are a place to be in public but from a ‘safe’ and private vantage point.”

Develop a habit of resource sharing before crisis occurs

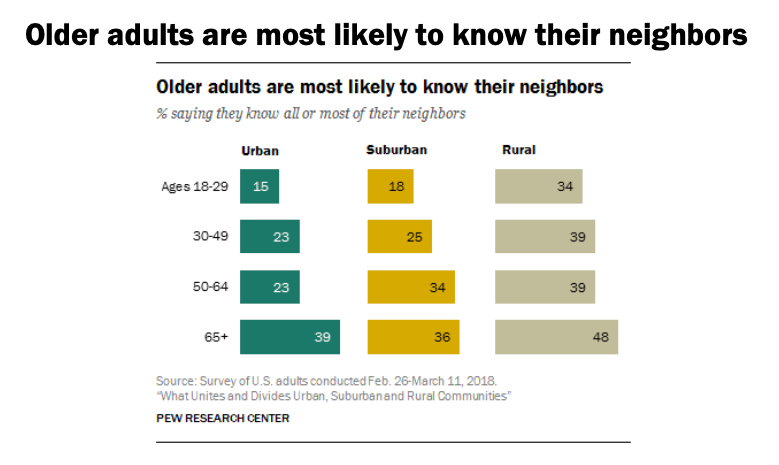

Early on in the Covid epidemic, I found myself in a situation where I needed a mask, right at the time when masks were most difficult to find. Lucky for me, a neighbor offered to give me a spare one he had on hand. I felt comfortable both asking for and receiving the mask because we had a relationship based on reciprocity that predated the epidemic. But most Americans are not used to going to neighbors for help. In fact, even among rural residents, who are most likely to be familiar with their neighbors, only a minority reported being knowing with all or most of their neighbors in a 2018 study conducted by the Pew Research Center. Only 15% of urban dwellers aged 15 to 29 reporting knowing all or most of their neighbor, the lowest number reported in the survey.

There are many explanations for these trends, but those explanations do not remedy the danger that can result from living without social connection to your surrounding community. However, the nature of cohousing gets people accustomed to sharing resources and going to each other for help. From grocery runs for vulnerable residents at risk of contracting the virus to supervising kids whose parents are busy working remotely, the complex webs of social capital and resource sharing engendered by cohousing has helped to cushion residents in challenging times, adapting swifter and with great ease to changing conditions.

“Being in community allows people to make a change because we already have relationships and trust and care about each other,” said Michele Domash, a Puget Ridge Cohousing resident who participated in the creation and design of the community.

There are many ways for urban planners, architects, and community organizers to design places and experiences that facilitate resource sharing before crises occur. The Capitol Hill Tool Library, which offers equipment rentals, DIY classes, and opportunities to participate in sustainable community projects, is one example of an organization dedicated to these goals. Community centers, public libraries, and schools can also be leveraged by cities to connect residents and build a sharing economy.

Harness the wisdom of the group

One of the most important things Kim said she has learned from living in cohousing is the value of “the wisdom of the group” “This is a phrase we use a lot – often referring to difficult decisions we have to make and the uncertainty going into a meeting,” Kim said. “And yet we always end up leaving with a great solution that none of us had walking in.”

This practice requires creating an environment in which all members feel comfortable communicating and feel that their opinion will be valued. It also takes time and a willingness to listen to others and learn from their experiences. At Puget Ridge Cohousing, decisions are made using a consensus based model, which the members interviewed agreed was time consuming and could at times be frustrating. Yet, similar to Kim, they also felt that consensus based decision making ultimately achieved better outcomes. At a time in which our nation grapples with the consequences of years of decision making that did not adequately recognize or value the experience of marginalized minority groups, an important lesson about honoring both the individuals that comprise the group and the group itself might be drawn from cohousing.

Additionally, living in community means living with people with different levels of knowledge and skillsets, which can be incredibly useful- especially during a time of emergency like a pandemic. At Puget Ridge, decisions regarding how to implement social distancing in the community and how to properly sanitize shared spaces were created by a volunteer task force medical professionals residing within the community. The knowledge shared by these community members played an important role in keeping everyone safe during the early and uncertain days of the pandemic.

Work to achieve diversity

It is important to note that while cohousing has many positive qualities, at this point diversity is not one of them. As a whole, cohousing communities are whiter and more affluent than the United States’ population at-large. “PugetRidge, like most CoHousing, is a bastion of whiteness,” said Amy Darling, “Leading up to (late February) and during the pandemic quarantine, I observed with both fascination and distress how white/dominant culture infused communication, organization and culture.”

Darling, who is white, went on to explain how she and other members of Puget Ridge have created a group to engage in discussion and awareness building around white supremacy and privilege, which has led Darling to feel a “sustained love for [her] village.”

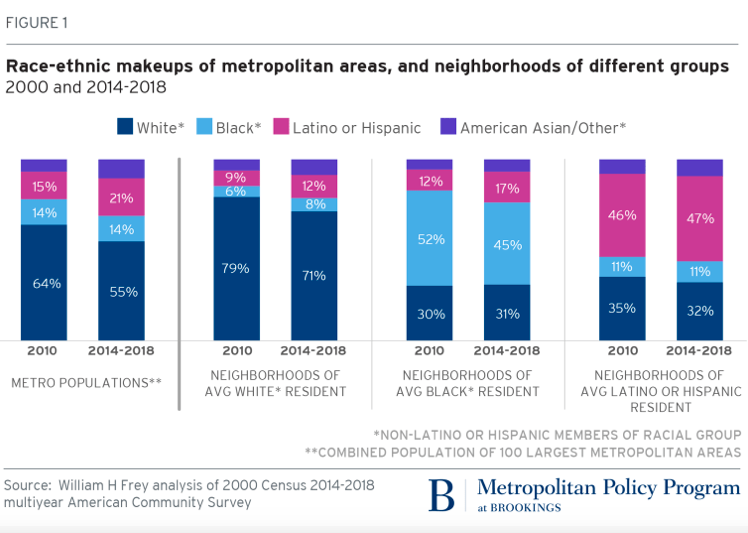

But not only cohousing communities suffer from a lack of diversity. Even as racial diversity has increased in the United States, data from the Brookings Institution found that in all US metro areas, white people are still more likely to live in a majority white neighborhoods by a significant margin.

Increasing diversity within neighborhoods is something the US needs to make strides on, and changing zoning policies to allow for the construction of more multifamily and low-income housing can make a difference. Sadly–and not surprisingly–our current president seems bent on doing everything he can to prevent these changes from happening. President Trump has been recently boasting about his work to end President Obama’s Affirmatively Further Fair Housing (AFFH) rule and block construction of low-income housing, claiming that presidential contender Joe Biden wants to “abolish the suburbs.” However, his approval low ratings with suburban voters indicate he might be off the mark.

To circle back to cohousing, some cohousing advocates are already trying increase diversity by addressing issues related to privilege and affordability. “The good news is that affordability is a hot topic within the cohousing world,” wrote Cynthia Dettman in an article for Shareable. “Creative solutions are beginning to emerge, with some good results… communities are expanding affordable options, including government-subsidized units, shared housing, and construction and rental of small accessory buildings.”

So far the solutions for increasing diversity among cohousing communities look a lot like the same solutions housing advocates have been fighting for some time. And similarly, some of the solutions offered by cohousing for living in a Covid city are not so different from good community design principles that can be incorporated to some degree into any community at any time.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.