But will Seattle stop acting like it before it’s too late?

With the Covid-19 crisis dragging on, and the climate crisis setting us up for an extended smoke event — it’s almost possible to forget that the housing crisis never abated. This, despite declaring an emergency back in 2015. Fortunately, thanks to legislation passed in 2019 by the City Council, the City of Seattle was obligated to review the Comprehensive Plan (CP) with the race and equity toolkit. While the city has not released a full report based on these findings, the Office of Planning and Community Development has released a staff report summarizing the study’s initial findings.

This staff report is the start for public outreach on what will eventually be the next major comprehensive plan update. However, we’ve been down this road before: Seattle has published a number of comprehensive plans going back to 1994, each one promising a glorious progressive future, only to run into the same problems, many of which trace back to the original CP of 1994. To understand why, we have to go back to the history of this plan.

The 1994 plan introduced the “Urban Village Strategy” (UVS), which restricts the areas of the city where new multifamily buildings (i.e., apartments) can be constructed. Much has changed in Seattle since 1994, but our development strategy predates Windows 95. Like trying to run modern software on an old computer, our present housing crisis can be likened to trying to respond to present conditions with an outdated “operating system.” Even worse than that, the 1994 plan wasn’t truly new, but rather a product of disturbing parts of our history. It is important to understand this history so we can make a clean break from it.

Seattle was a much smaller town in 1994, with about 530,000 people as compared to over 730,000 today. The city was finally recovering from the “Boeing bust” layoffs and the accompanying population decline. Regional transit funding was still struggling to turn the page from failed rail packages in 1968 and 1970. There were many reasons to be optimistic about the future. A young company named Microsoft was growing nearby and the city was not so dependent anymore on Boeing for its economic future. Bill Clinton had been elected in 1992 and had promised to solve the nation’s rising healthcare costs. Locally, Seattle had just re-elected our first Black mayor, Norm Rice.

Despite these positive trends and many people’s best intentions, 1994 and the Comprehensive Plan ended up locking in some of the most unfair tendencies of Seattle’s past. To understand what these were, we have to go back to the beginning.

Precursors to The Plan: Injustice and Struggle

The City of Seattle was founded and named after Chief Seattle of the Duwamish and Suquamish Tribes. Nevertheless, early European settlers promptly banned native people from living here. Later the United States Government would burn down Chief Seattle’s longhouse. Today, the Duwamish tribe is struggling to achieve recognition by the federal government.

Seattle sided with the Union in the American civil war but in 1886 many of its white citizens rioted and successfully evicted Chinese immigrants from their homes. In spite of this, as Seattle’s population grew, people of all races came to live and work here. In line with national trends, White people in Seattle objected to people of all races living close by and sought to prevent this by means legal and otherwise.

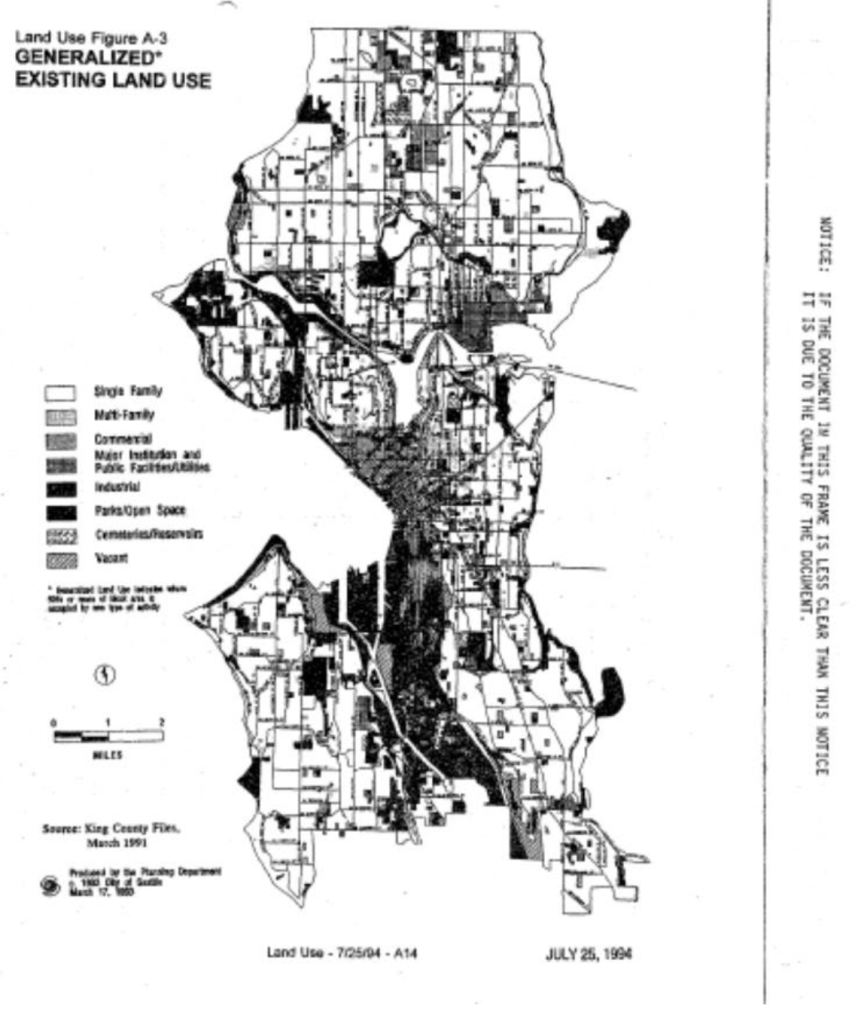

With the help of the Supreme Court, racial covenants became common in the United States from 1926 until 1948, when the court reversed itself. A covenant meant that a white property owner wasn’t allowed to sell their home to a person of color. The result of these covenants was a concentration of people of color in specific areas, including the Central District and the Rainier Valley. In the 1930s, Seattle joined many cities around the country where maps told lenders that areas with many people of color were “high risk” areas. The result was lending processes wherein people in these areas could not get access to home finance, no matter how good their individual credit was. This “redlining” would continue into the 1970s.

In parallel with racial conflict, Seattle has also long struggled with a class divide. In the 19th and 20th centuries, growth of industry created new groups of capitalists and workers. Seattle was a boomtown for labor organizing and working class politics. The International Workers of the World and many socialist groups together had a major presence in the city. This led most dramatically to the 1919 general strike, during which workers briefly shut down the business of the city, greatly alarming the owners of enterprises and more conservative elements.

At the intersection of the class and racial divides were attempts to limit where certain kinds of dwellings could be constructed. Seattle would increasingly adopt Residential Exclusionary Zoning (REZ), a government regulation system focused on the types of residential structures allowed and disallowed in various areas.

A critical moment for Seattle was the 1923 zoning ordinance. Seattle hired Harland Bartholomew, a man who had crafted many explicitly racial zoning ordinances in other cities. Unlike prior building laws which were focused on fire prevention, the 1923 code began a process of building size restrictions, which would continue for decades. Not coincidentally, in Seattle we saw racial covenants and redlining exclude people in ways the zoning code could not.

By the 1960s and 1970s, the national civil rights movement helped inspire Seattle activists to challenge the legality of race based housing discrimination. It was a long and tough battle. The City Council put elimination of housing discrimination on the ballot and a majority of voters rejected it. It was only after the death of Martin Luther King Jr. that the City Council finally stood up and passed a ban on housing discrimination.

The city saw a similar odyssey with regards to highways and transportation. Seattle famously bought up its streetcar system from its private operator only to find the system in need of such maintenance that the city went and tore it up soon after. Funds for new highways were easier to come by: when I-5 was completed through Seattle in 1965, it tore a path through the center city, cutting off neighborhoods from each other. Citizens had to fight to prevent the R.H. Thompson expressway from similarly demolishing and dividing Seattle’s Central District. Efforts to fund a high quality mass transit system foundered first in 1968 and then again in 1970.

During this time period, Seattle continued to restrict the possibilities for multifamily housing in much of the city. The “single family” zoning became the default zone in vast areas of the city where multifamily structures were not already prevalent. Some multifamily structures still managed to get in though, either before these restrictions or through spot zoning changes.

The 1994 Comprehensive Plan: Forward or Backwards?

The Washington State Growth Management Act (GMA) of 1990 required Seattle and other cities to create a plan for designating growth in specific areas. The GMA saw this as a necessary step to accommodate growth without further destruction of farmland and natural areas on the urban fringe.

There was reason to be optimistic: The re-election of Rice as Seattle’s first Black mayor was a refutation of the Seattle which just a few decades prior had voted down restrictions on racial housing discrimination. Unfortunately, Seattle responded to the GMA mandate by bringing the toxic logic of existing land use laws into the Comprehensive Plan.

Things started to go awry with the stated goal of 1994 Comprehensive Plan to: “Maintain and enhance Seattle’s character. Seattle’s character includes large single family areas of detached houses both inside and outside of villages, many thriving multifamily areas, neighborhood commercial areas, industrial areas, major institutions and a densely developed downtown with surrounding high density neighborhoods” (page 5).

The CP implemented this by creating the Urban Village Strategy. The basic premise of the UVS was to limit where apartment buildings could be built to select areas of the city. The stated criteria for inclusion in an urban village were areas “…where: 1) natural conditions, the existing development pattern, and current zoning are conducive to support denser, mixed-use pedestrian environments where public amenities and services can efficiently and effectively provided, 2) access to transportation facilities is good or can be improved, 3) public and private facilities, services and amenities, such as parks, schools, commercial services, and other community services, are available, or can be provided over time and 4) existing public infrastructure has capacity or potential to accommodate growth” (page 7).

Despite these criteria, the drafters did not feel comfortable passing into law urban village designations outside of the urban core. That job they left to the “neighborhood planning” process. Recall if you will that racial covenants, redlining and restrictive zoning had for decades restricted who could move to a neighborhood and ultimately participate in the neighborhood planning process.

The drafters also didn’t fully trust the neighborhood planning process, stating: “… if at the end of the neighborhood planning cycle, a village boundary has not been established for a hub or residential urban village, the boundary shown in Land Use Appendix A of this plan shall become the boundary for that urban village” (page 10). On the whole, the framers of the 1994 plan got their way, with the urban villages created out of the neighborhood planning process resembling those proposed in 1994, with few exceptions.

The 1994 plan states its intent to: “Accommodate planned levels of household and employment growth” (page 6). Alarmingly, there wasn’t any provision for the possibility that there might be more growth than planned for. Nevertheless, the plan’s stated time horizon was 20 years or until 2014. Coincidentally or not, this corresponds with the steepening of Seattle’s housing crisis.

This failure can’t entirely be heaped upon the creators of the 1994 CP. In 1994, the city had not seen the full effects of deepening income inequality. The nation was only two years into the Clinton administration. In November of 1994, the Republican takeover of congress would have profound implications on the continuation of Reaganite policies through the rest of the decade and beyond.

Global warming and the growing global ecological crisis were also just beginning to gain critical public attention. The 1992 framework for addressing climate change only went into force with “non-binding” restrictions in 1994. It would take until 1997 for an attempt at binding restrictions with the Kyoto Protocol. The increased severity of the crisis and the inadequacy of these measures has since become apparent. In 1994, planners weren’t considering suburban sprawl as a driver of climate change — now we know that green infill housing, and moving our least dense neighborhoods to transit-supporting densities, are key factors in addressing climate change.

Income inequality combined with rapidly rising housing costs have amplified the effects of exclusionary zoning: only the richest among us can now afford to buy or rent houses in our single-family zones, making this zoning designation effectively more exclusionary than ever.

While the Rice administration was a watershed moment that moved us forward, the 1994 plan locked in exclusionary zoning in ways that still haunt us. We’re about as many years past the 1994 plan it was from fair housing legislation in 1968. It’s time that we act like it.

What’s Next?

Fast forward to today, and the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) staff report shows that a number of people in the city are already moving in the right direction. Our main quibble with the OPCD memo is that it doesn’t go far enough. The Urban Village Strategy evolved from redlining, racial covenants, and class based fear. Rather than “reforming” the UVS, it’s time to be talking about starting over with a new strategy. One idea is for something we call a “Welcoming Communities Strategy.” What does this entail? We have some ideas, which we will write about more in the near future, but we want to hear yours, and perhaps most importantly, the powers that be in the city should hear them as well.

Housing Now Seattle is an informal collective and we’re constantly learning and growing. We encourage you to stay in touch with us on Facebook and Twitter and if you’d like to receive housing advocacy alerts feel free to sign up to volunteer! Also, please also like and follow our sister organization and radically progressive land use co-conspirators Share the Cities. They are conducting meetings and outreach about the 2024 Comprehensive Plan.