Washington’s missing middle housing bill, HB 1110, continues to move through the state legislative process. On Friday, it passed out of the House Appropriations Committee and onto the House Rules Committee with a slate of substantive changes paring it back. It has until 5:00pm on March 8th to pass out of the House completely. Meanwhile its companion bill in the Senate, SB 5190, is dead after stalling out in the Senate Ways and Means Committee.

The Senate, nevertheless, is still moving ahead with a separate zoning reform bill, SB 5466, focused around transit-oriented development. That bill is now on the same deadline as HB 1110 to pass completely out of its chamber of origin. Whether one or both bills are approved this year is an open question, but their sponsors have the backing of Governor Jay Inslee, who has made increasing urban housing supply a key legislative priority, as well as some allies in the Republican delegation.

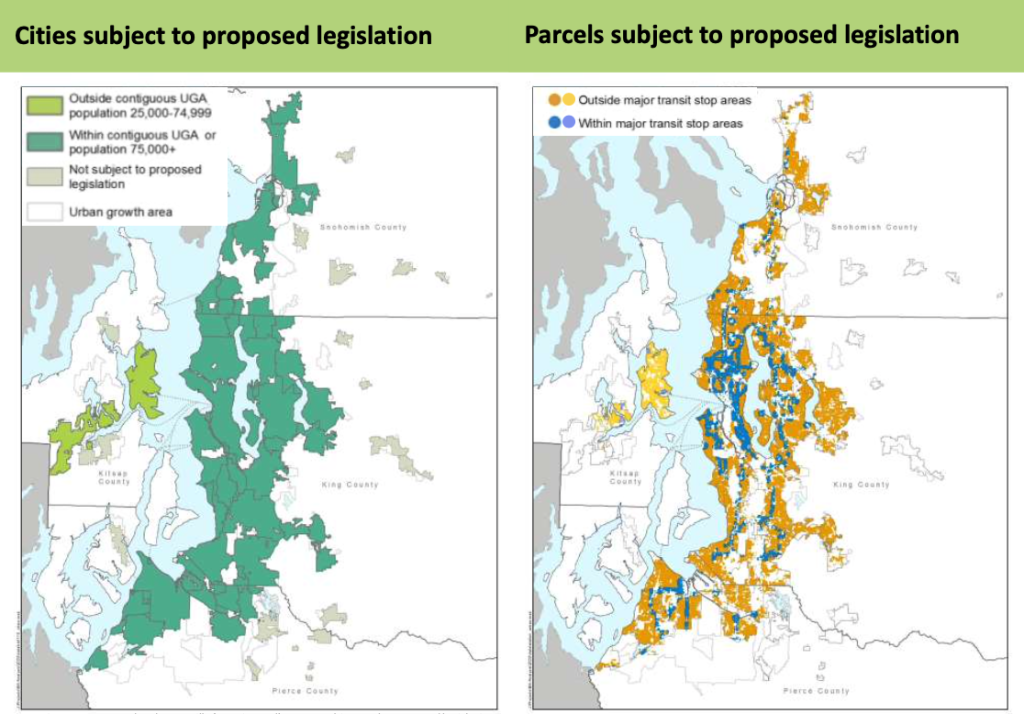

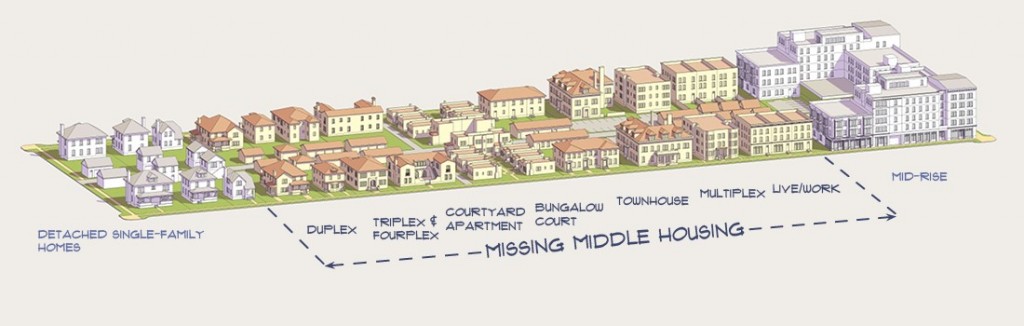

HB 1110 started out as a relatively simple bill requiring cities subject to the law to allow at least four homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use and six homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use if two homes are affordable or the lot is within a half-mile of a major transit stop. Most cities planning under the Growth Management Act would have needed to make these and other related zoning changes if they either had at least 6,000 residents or were in a contiguous urban growth area with a city of more than 200,000 residents (e.g., Seattle, Tacoma, and Spokane). But pressure from state legislators and other local interests have resulted in substantial changes to the bill.

To get HB 1110 out of the House Housing Committee, the scope of the bill was pared back to cover fewer cities in the state and also reduce the number of housing units were required per lot in some cases. Other substantive changes, like higher parking mandates, were made to the bill, and it was moved onto the House Appropriations Committee. That committee did adopt several further amendments to the bill, such as further exemptions for critical areas, reduced major transit stop and community amenity areas, and a paring back of the types of missing middle housing cities need to legalize. However, amendments also made it easier to eliminate off-street parking mandates in urban areas and constrained some of the “substantial conformance” certification language for cities adopting comprehensive plans prior to the legislation.

| Topic | Original Bill | 1st Substitute | 2nd Substitute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applicability | Any city with 6,000 or more residents or any city in a contiguous urban growth area with a city above 200,000 residents | Any city with 25,000 or more residents or any city in a contiguous urban growth area with a city above 200,000 residents | Same as the 1st Substitute |

| Definition of “Major Transit Stop” | A “Major Transit Stop” is defined as a stop on high capacity transit system funded or expanded by Sound Transit, a commuter rail stop, a stop on a rail or fixed guideway system, a stop on bus rapid transit routes, a stop on certain transit routes that operate at certain frequencies, any state ferry terminal, or any stop considered to be a major transit stop by the Puget Sound Regional Council | Same as the Original Bill, except that stops on certain transit routes that operate at certain frequencies and state ferry terminals were removed from the definition | Same as 1st Substitute |

| Definition of “Community Amenity” | N/A | A “Community Amenity” is defined as a public school, common school, private school, or an entrance to a public park operated by a local or state government | Same as 1st Substitute, except that private schools were removed and “public park” became “community public park” |

| Definition of “Critical Areas” | Same as existing law | Same as existing law | Added text includes watersheds that are listed as impaired or threatened under the Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act and serve a reservoir used for potable water |

| Definition of “Middle Housing” | “Middle Housing” is defined as two or more attached, stacked, or clustered homes, including duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, fiveplexes, sixplexes, townhouses, courtyard apartments, and cottage housing | Same as Original Bill | Same as Original Bill |

| Density Allowances | At least four homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use, and six homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use if two homes are affordable or the lot is within a half-mile of a major transit stop | For cities with at least 25,000 residents but less than 75,000 residents, at least two homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use, and four homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use if one home is affordable or the lot is within a half-mile of a major transit stop or community amenity; for cities with at least 75,000 residents or any city in a contiguous urban growth area with a city above 200,000 residents, at least four homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use, and six homes per lot on all lots zoned for residential use if two homes is affordable or the lot is within a half-mile of a major transit stop or community amenity | Same as 1st Substitute, except that the major transit stop and community amenity areas are reduced to a quarter-mile for cities with at least 75,000 residents or any city in a contiguous urban growth area with a city above 200,000 residents |

| Affordable Housing Requirement(s) | Additional homes allowed under the affordable provision must be affordable to low-income households for at least 50 years | Same as Original Bill | Same as Original Bill, except that it adds standards for affordable housing sizes and configuration as well as allows cities with affordable housing incentive zoning programs to vary standards and subject all middle housing to participation in the incentive zoning programs |

| Anti-Displacement | Cities without anti-displacement measures in a Housing Element must adopt adopted specified measures | Removed and remodeled to be a cause for implementation extension (see below) | Same as 1st Substitute |

| Development Standards | Cities may only adopt objective development and design standards for middle housing and such standards cannot discourage and make impractical development, and development regulations cannot otherwise be more restrictive than required for single-family homes | Cities may only adopt objective development and design standards for middle housing, development regulations cannot otherwise be more restrictive than required for single-family homes, and design review can only be administrative | Same as 1st Substitute, except that cities only have to allow six of the eight middle housing types |

| Review Processes | Middle housing shall use the same permitting and environmental review processes as single-family homes | Same as Original Bill, except a caveat is added that other state law may require additional requirements on middle housing, such as Shoreline Management Act regulations and state building, energy, and electrical codes | Same as 1st Substitute |

| Off-Street Parking | For middle housing, off-street parking shall not be required within a half-mile of a major transit stop, no more than one off-street parking space shall be required per lot on lots smaller than 6,000 square feet, and no more than two off-street parking spaces shall be required per lot on lots greater than 6,000 square feet | Same as Original Bill, except that no more than one off-street parking space shall be required per home on lots smaller than 6,000 square feet and no more than two off-street parking spaces shall be required per home on lots greater than 6,000 square feet, provided that a city may require more off-street parking if a professional study with empirical evidence demonstrates that less off-street parking in a defined area would make on-street parking infeasible or unsafe for middle housing | Same as 1st Substitute, but adjusts the provision allowing higher off-street parking mandates if a city completes a professional study demonstrating that the lower off-street parking mandate limits would be “significantly less safe for vehicle drivers or passengers, pedestrians, or bicyclists if the jurisdiction’s parking requirements were applied to the same location for the same number of detached houses,” but only if the Department of Commerce concurs with and certifies an application demonstrating this, or for portions of cities within one mile of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport |

| Implementation Timing | The regulatory requirements would take effect the later of two years after the bill’s effective date for cities with 10,000 or more residents or one year after a city is determined to reach a population threshold | The regulatory requirements would take effect the later of six months after a city’s next major comprehensive plan update (2024 for Puget Sound cities) or more residents or one year after a city is determined to reach a population threshold | Same as 1st Substitute |

| Implementation Extensions | A city may apply for a middle housing implementation extension, but only for specific areas where a city can demonstrate deficiencies in water, sewer, and stormwater services now or anticipated within five year, which the Department of Commerce may certify and may renew only one additional time, but the city must provide a plan of action to remedy the deficiencies on a specific timeline | Similar to the Original Bill, except that 1) the five year time period doesn’t apply, 2) additional extensions are not inherently limited, 3) that the provisions require that a city include any needed improvements in a capital facilities plan or identify which special district is responsible for providing the needed improvements, 4) that cities still must allow development in deficient areas if a developer commits to delivering needed improvements, and 5) a city may separately apply for a middle housing implementation extension for areas at risk of displacement as determined by a local anti-displacement analysis, provided that a plan to implement anti-displacement policies is devised, which the Department of Commerce may certify | Same as Original Bill |

| Commerce Responsibilities | Department of Commerce is required to develop technical assistance for cities implementing middle housing, publish a model ordinance within 18 months of the middle housing law (the model ordinance takes effect in cities that fail to take action to implement the law), and establish a process to certify cities’ conformance with the middle housing law | Same as Original Bill, except that publishing of the model ordinance is expedited to within six month of the middle housing law and allowing certification of cities’ substantial conformance with the middle housing law as long as the overall increase in density throughout cities is at least 75% of the required density on single-family lots and this was part of a recent comprehensive plan update | Same as 1st Substitute, except that additional conditions to substantial conformance certification flexibility for cities that allow middle housing throughout a city rather than just targeted location and where additional density is allowed near major transit stops and community amenities and for projects that incorporate affordable housing |

| Red Tape Removal | City actions to implement the middle housing law, as certified by the Department of Commerce, are exempt from appeals under the Growth Management Act and State Environmental Policy Act, except that the Department of Commerce’s certification or denial of local actions may be appealed to the Growth Management Hearings Board | Same as Original Bill | Same as Original Bill, but provides a categorical exemption from the State Environmental Policy act for government actions to remove off-street parking requirements in urban growth areas |

| Covenants and Restrictions Preemptions | New covenants and restrictions by homeowner communities are preempted from banning middle housing stipulated under the middle housing law | Same as Original Bill | Same as Original Bill |

Despite the changes, the missing middle housing bill would still re-legalize duplexes and fourplexes throughout smaller cities as well as fourplexes and sixplexes in larger cities and cities in larger metropolitan areas. That could be quite impactful in parts of the state, including in Puget Sound where the legislation could buy nearly a decade of real development capacity. Even with the subsequent scope reductions, the impact on housing creation could be significant. An analysis by the Puget Sound Regional Council projected an increase of more than 200,000 homes over a 20 year time span in the Puget Sound region alone if the original bill was implemented. The bulk of those gains would still hold in the amended version.

However, there are big questions with some provisions of the amended legislation. These center on potential affordable housing requirements and critical areas exemptions.

Affordable housing requirements were always tied into the legislation for bonus units, including provisions prescribing the design of affordable housing units, but the latest version of the legislation allow cities to vary from that if they have established an affordable housing incentive zoning program under RCW 36.70A.540, such as Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability Program. The latest version of the legislation also allows such cities to impose incentive zoning programs on missing middle housing allowed under the legislation.

The legislation doesn’t put enactment timing parameters on incentive zoning, which might encourage cities that have traditionally acted in bad faith to impose their own incentive zoning programs designed to make missing middle housing economically infeasible. On the flip side, absent the text in the legislation, cities may have been able to impose these incentive zoning programs under RCW 36.70A.540 anyway. Regardless, the wording of the text is debatable if it only applies to cities that have enacted an incentive zoning program prior to the city becoming subject to the missing middle housing legislation or if any city at any time can enact an incentive zoning program — state legislative research staff seem to believe the latter in their assessment. This may be a policy issue state legislators want to deal with more directly now, especially to ward off misuse by traditional bad actors like Mercer Island and Edmonds.

As for critical areas, the legislation contains a big exemption to missing middle housing for any lot, regardless how of encumbered it might be. And the text of what “critical areas” is defined as has also been expanded to include impaired or threatened watersheds, as listed under the Clean Water Act, that serve reservoirs used for potable water. These sets of exemptions are peculiar and should raise a lot of questions for legislators.

Firstly, state law already defines what features are considered critical areas and requires that cities protect them. However, protecting them doesn’t typically mean that development — even high-density development — is outright prohibited on a lot. It’s not unusual for urban lots to have a small wetland or buffer portion of a wetland to fall under it while the remainder is free and clear for development. Cities require the wetland features to be protected, but otherwise let lots be developed with any number of uses and density allowed on it under local zoning ordinances. The same is the case for lots with some steep slopes or flood hazards. The proposed bill takes a dramatically different turn by fully exempting any lots with critical areas on them from missing middle housing requirements, which is very incongruent with the current approach to critical areas at the local level.

Secondly, it’s unclear what the scope of impaired or threatened watersheds might be in cities to be covered by the legislation. Watersheds are typically very large geographic areas and many streams and other waterbodies are impaired or threatened, regardless of whether they’re in urban or rural areas. It’s not a unique thing in communities. The provision, however, is tied to these watersheds serving a reservoir used for potable water. Depending upon how this is interpreted, that could narrow the number of watersheds and areas affected by the provision, but the legislation doesn’t define a reservoir, which could be interpreted as a water tower or an open water storage area. Regardless, exempting whole watersheds from new missing middle housing requirements that are likely to improve water quality overall is a bizarre policy choice.

A boutique amendment that would have added an exemption for Bainbridge Island and potentially Oak Harbor was withdrawn before a vote in the Appropriations Committee. Representative of Tarra Simmons of Kitsap County had proposed a broad exemption from the missing middle housing requirements for any city on an island with a sole source aquifer, which therefore would have covered one and possibly both cities. While much of Bainbridge Island is fairly low-density — and curiously not rural unincorporated — beyond a mile from the ferry terminal, exempting the whole city-island would be a peculiar precedent to set when parts of the city center allow substantial infill housing opportunities. It’s still possible that a version of the amendment could come back for a floor vote in the House.

In the meantime, it’s really a matter of wait and see. HB 1110 still has until the March 8th house of origin cutoff to move out of the House, so any number of things could transpire in that period. Things can and do move fast in the state legislature, but the important thing is that this bill is still very much in play with a good shot at passage.

Comment on HB 1110 and sign in as “pro.”

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.