Washington needs abundant, affordable, and accessible housing. Accordingly, this legislative session made progress on housing density (via HB 1110, HB 1337, SB 5190, and SB 5466) by enhancing various “-plexes”, accessory dwelling units, and transit-oriented development.

Conversations surrounding this legislation have lauded the bipartisan support and benefits for housing availability and others lamented perceived neighborhood “character” degradation. Comparatively little attention has focused on fish and wildlife beyond occasional critiques, such as those described in a March 26 Seattle Times article, bemoaning presumed unavoidable biodiversity degradation.

Indeed, development has eroded our state’s fish and wildlife habitats. But not because of densification, just generally poor development practices.

The weight of conservation science supports this legislations’ actions. Harm to habitats and species from denser development are not inevitable. In fact, denser housing offers a win-win for Washingtonians and biodiversity, if implemented thoughtfully.

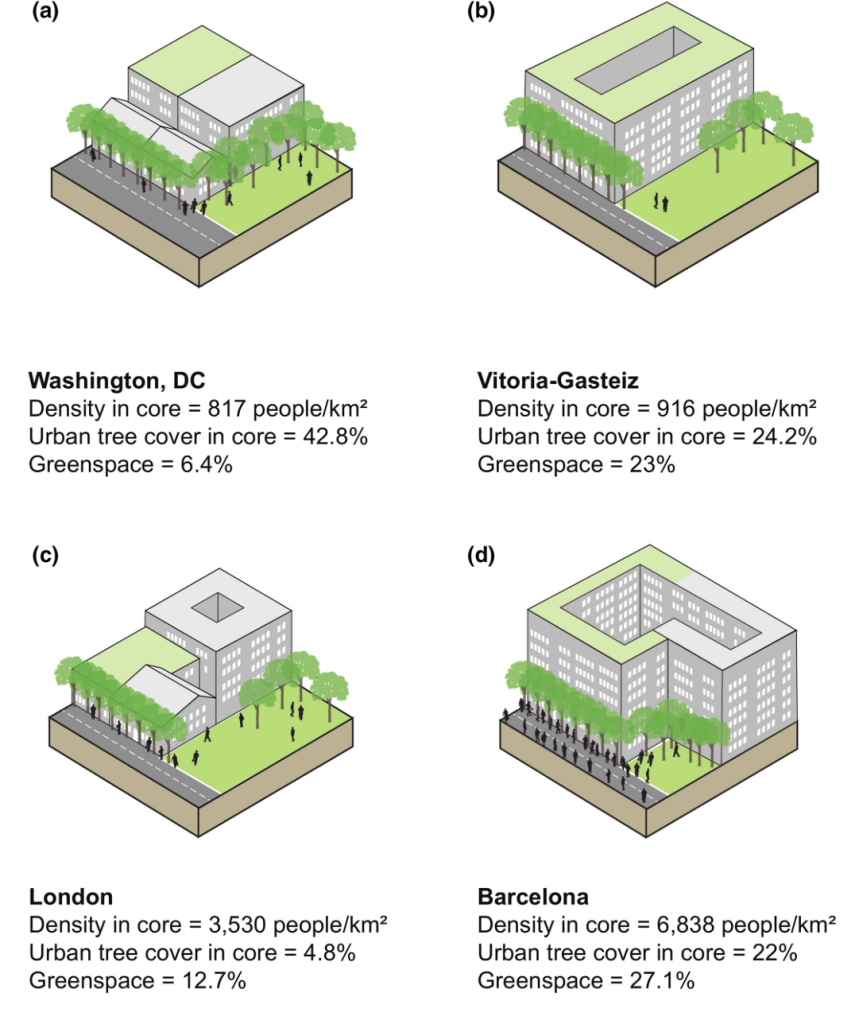

For instance, a 2023 study in the journal ‘Nature and People’ analyzed U.S. neighborhood density and tree abundance. Unsurprisingly, the study showed that denser neighborhood blocks had less space for trees. Yet, this pattern was astonishingly weak. Some dense neighborhoods smoosh houses tightly, filling the gaps with concrete instead of trees.

Other neighborhoods were nature “bright spots”. These were just as dense as smooshed neighborhoods but maintained numerous trees and other green areas for people to play and biodiversity to thrive.

This study detailed science-based approaches for supporting biodiversity with denser housing. These include preserving existing habitat patches, protecting buffers around streams, and creating parks for wildlife and people. It also includes augmenting stormwater infrastructure like rain gardens and ponds, and greening vacant land and peripheries of buildings. These tools provide habitat for birds, frogs, mammals, and butterflies while minimizing downstream habitat impacts.

Importantly, nature-centered densification advances equity and justice. In 2020 in the journal ‘Science’, my colleagues and I reviewed urban biodiversity research. We found that racist and classist development practices – particularly around housing – have cascading negative consequences for fish, wildlife, and ecosystems. Discrimination is clearly terrible for people, and it also devastates the abundance, diversity, and health of wildlife.

These biodiversity impacts have compounding harms on our communities. Mounting scientific evidence demonstrates that experiencing biodiversity – not just green places like parks – improves our health and wellbeing. For instance, a 2018 study in the journal ‘Frontiers in Psychology’ found that experiencing more biodiversity – more types of plants, butterflies, and birds – enhanced the restorative mental health benefits of spending time in urban parks. Green places make us healthier, but the more wildlife we experience in those places amplifies those benefits.

Scientists – including in Washington – have long concluded that urban density is essential for conserving biodiversity by minimizing sprawling suburbs. It’s fair to say those conclusions haven’t produced widespread, meaningful improvements in development practices. Even so, conservation science continues to debate how to best protect wildlife and habitats through land sharing (“gentler” forms of development and farming dispersed throughout “nature”) or land sparing (intensive development cordoned off from undisturbed “nature”). Although the jury is still out on sparing versus sharing as a general rule, denser development that integrates nature offers us an opportunity for both sharing and sparing ecosystems in our cities and our hinterlands. We can make housing available to more people and share our neighborhoods with non-human animals, all while sparing nearby forests, beaches, shrublands, and prairies from our heaviest impacts.

It will take concerted effort by multiple state regulators and city and county governments, culture change by developers, and continued advocacy by local communities to ensure Washington’s housing practices are equitable, just, and conservation focused.

The science is clear: our cities can both densify and bolster biodiversity to foster the healthy communities Washington deserves.

Housing policy is conservation policy. Equitable housing is conservation.

Max Lambert (Guest Contributor)

Dr. Max Lambert earned his PhD from Yale University in 2018 in environmental studies where he studied urban and suburban wildlife conservation. He is currently based in the Puget Sound region where he is a wildlife research scientist who studies solutions to our region’s and state’s pressing conservation challenges.