WALeg Wednesday considers the housing package that passed, led by HB 1110.

As the legislative calendar winds its way to adjourning sine die (until next year) on Saturday, it’s easy to focus on issues that were lost in the process or ideal bills that did not get out of the legislature. Rent stabilization failed in all forms, as did most tenants’ rights legislation. Bills about transit-oriented development and giving homeowners the right to split oversized lots made it through one chamber but not the other. And all of the bills that did pass were watered down with significant concessions, including the point access building legislation that went from allowing single stair buildings to punting the rulemaking to a study group.

It’s important to recognize that the laws which did pass are impressive. And now we have a firm list of four important measures that will reach the governor’s desk as they have fully completed their legislative approvals.

First, the hard work of Representative Davina Duerr (D – Bothell), the folks at Futurewise, and a host of advocates pushed through a climate bill that was three years in the making. HB 1181 requires all comprehensive plans to include a climate change and resiliency component that shows how jurisdictions will create the green, accessible infrastructure needed to respond to our warming planet. The plans must specifically look at greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles, the region’s largest contributor to climate change. In the past, the only time plans mentioned “climate” was to talk about improving the business climate. Considering the Earth’s climate in a comp plan amounts to a sea change just in time to match their rising levels.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) will be allowed throughout the state under HB 1337. The legislation compels cities to permit two ADUs, detached or attached, on all residential lots. The units may be up to 2 stories and 1,000 square feet on any legal residential lot, and the rules have to be in place by six months after a jurisdiction’s next comprehensive planning update. There are also requirements on dropping parking requirements, impact fees, residency requirements, and multiple ADU provisions.

Also fully passing the legislature is HB 1293 which streamlines development regulations. The bill accelerates the permitting and design review by committee process by requiring “only clear and objective design review standards.” Such ascertainable standards that do not result in a reduction of density can only be assessed during one (1) single public meeting that is consolidated into the rest of the permit review process. Historic districts and landmarks are exempt, but jurisdictions are encouraged to expedite approval for affordable dwelling units.

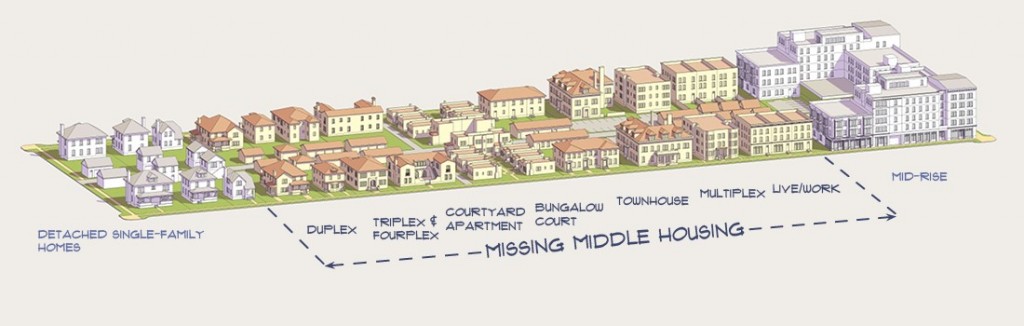

Of course, the big one is HB 1110 permitting missing middle housing to be developed across large portions of the state. The bill, sponsored by Representative Jessica Bateman (D – Olympia) and also supported by Futurewise, passed the legislature on Tuesday, April 18th as the House concurred with the Senate’s amendments by a vote of 79 to 18. What passed is a very different bill than it started in the house. The new rules require jurisdictions to permit more housing, increasing based on the state’s official size of the jurisdiction:

- Cities of at least 75,000 people must allow:

- four units per lot in all predominately residential zones

- six units per residential lot within 1/4 mile walking distance of a major transit stop

- six units per residential lot if two units are affordable

- Cities of 25,000 to 75,000 people must allow:

- two units per lot in all predominately residential zones

- four units per residential lot within 1/4 mile walking distance of a major transit stop

- four units per residential lot if one unit is affordable

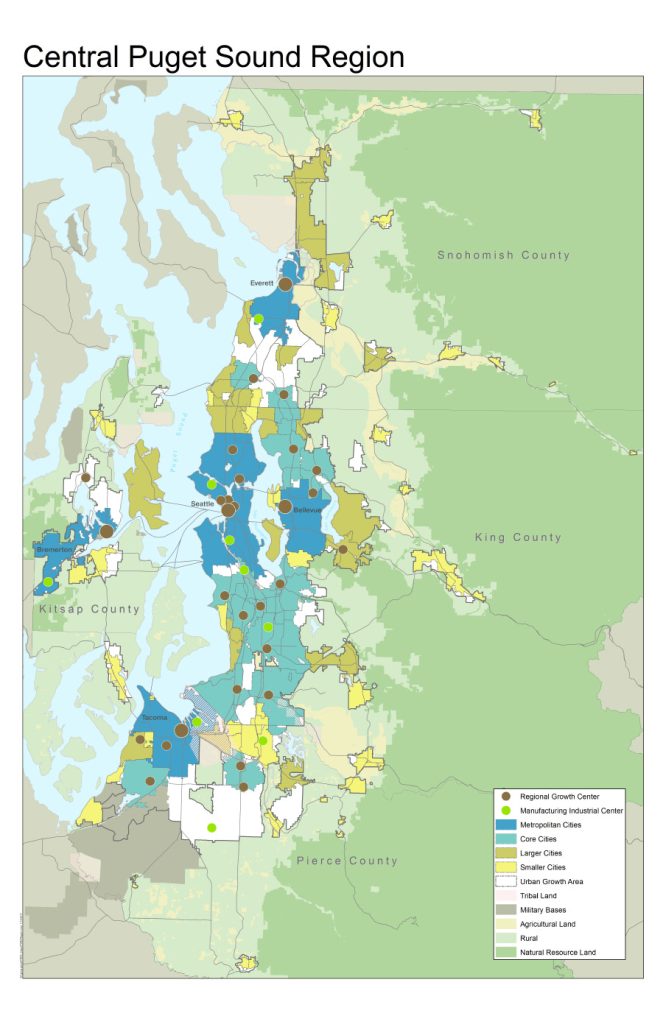

- Cities of less than 25,000 people “that are within a contiguous urban growth area with the largest city in a county with a population of more than 275,000” must allow:

- two units per lot in all predominately residential zones

For that last small city part, the law is being understood to apply only in King County, as it has the only city in the state with over 275,000 people. The wording is a bit weird, as a plain reading of the provision would suggest it applies to counties of over 275,000 people. Seven of Washington’s 39 counties would have met that threshold (with their largest city in parenthesis): Clark (Vancouver), King (Seattle), Kitsap (Bremerton), Pierce (Tacoma), Snohomish (Everett), Spokane (Spokane), and Thurston (Lacey, which surpassed Olympia last year). The rules are being understood to apply county-by-county, so the small jurisdictions in Pierce and Snohomish are not impacted by being within Seattle’s GMA.

But still, cities and towns with less than 25,000 people in a contiguous Urban Growth Boundary with Seattle must now allow at least a second unit on all the residential lots. We’re looking at you, Medina, sitting right off the highway and inside the growth area. Understandably, such towns will be required to increase units, but Skykomish out in the mountains will not. Still a huge benefit.

For the record, there are 23 counties in Washington that do not have a jurisdiction over 25,000 people, of which 11 don’t have 25,000 people in the entire county. The state’s population is quite clustered.

Considered together, these three tiers sound intricate, but make a pretty astounding change. Not only will large cities over 75,000 people be increasing the allowable density up to six units per lot, smaller cities will be doubling or quadrupling their allowable units. And just to fill in the small enclaves between, the smallest cities can no longer use their planning authority to exclude second units. The bill smartly focuses this allowable density measure on King County around Seattle, that does contain the most population and most sorely needs more housing.

It will be interesting to see how “towns” with planning authority like Yarrow Point, Hunt’s Point, and Beaux Arts Village take to being told to double the number of units on each lot just because they are within the catchment of Seattle’s growth management area. The comprehensive plans of all three municipalities are carbon copies, calling the towns virtually built out and touting their financial contribution to regional affordable housing rather than constructing it within their borders. One would expect these towns will likely fight coming under the rules of HB 1110.

It could be seen that the ADU and design review bills extend the impact of HB 1110. The missing middle bill specifically allows ADUs to fulfill unit density requirements. It also requires only administrative design review for middle housing. The new ADU and design review bills apply very similar rules all jurisdictions that engage in planning, without the size constraints.

Another cool feature of HB 1110 is that it requires cities to allow at least six of the nine types of middle housing, which it defines as duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, fiveplexes, sixplexes, townhouses, stacked flats, courtyard apartments, and cottage housing. Combining that with ADUs means that we’re not just talking about a different shape of housing, but potentially different ownership systems. A house doesn’t have to just be on its own lot any more.

We have discussed how zoning constraints are only one among several intertwined processes that keep middle and multifamily housing from being constructed. While the new law will not overcome some of the financing and deed covenants that stop non-detached housing, it’s written specifically to compel jurisdictions to unwind their subdivision rules that stand in the way.

Which gives us a good takeaway from these legislative wins. They’re absolutely going to impact the supply of housing. It remains to be seen (and kind of unlikely) if those impacts will fully double or quadruple the amount of units buildable and available in a specific place. But what these bills have done is expand what is considered housing. HB 1110 breaks down the monoculture of what housing looks like in the state. HB 1293 limits how design review can be weaponized against everything not single-family detached. And HB 1337 allows ADUs to eliminate the cloistered enclaves that use ownership to exclude residents.

In the original decision allowing zoning, the U.S. Supreme Court focused on detached houses and called apartment homes “mere parasites.” A century later, we know it’s the detached homes that are wasteful, lonely, and polluting. Now Washington’s definition of residential homes has expanded, including sixplexes and courtyard apartments and many different ways of owning them. Financing will start to follow, and the focus will turn to fully ending a true parasite: restrictive covenants that formerly barred people by race, but now prevent multi-family homes and ADUs in many subdivisions.

A second takeaway needs to be heard by the state’s micro-municipalities, who are put on notice that their segregationist zoning and intransigent stance on accepting a fair level of growth can be brought to a swift end. Some towns and cities will take these laws as an impetus to rethink their position on growth and go beyond the relatively modest requirements of HB 1110. Others are going to double down on the lobbying and litigation to get exempted from the rules. These bills should remind all jurisdictions that they are creatures of state laws. Their grab bag of municipal excuses are shrinking because the folks writing the laws are ready to make significant changes.

Note April 20, 2023: This piece was updated to reflect the interpretation that HB1110 only impacts King County and clarifying the date for HB 1337.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.